J U N E 2 0 10

2010 JOINT STR ATEGIC

PLAN ON INTELLECTUAL

PROPERT Y ENFORCEMENT

i

★ ★

Table of Contents

Letter to the President of the United States and to the Congress. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Enforcement Strategy Action Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Leading By Example

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Increasing Transparency

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Ensuring Eciency and Coordination

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Enforcing Our Rights Internationally

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Securing Our Supply Chain

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Building a Data-Driven Government

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Summary of Enforcement Strategy Action Items . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Agencies’ Intellectual Property Enforcement Missions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Department of Agriculture

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Department of Commerce

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Department of Health and Human Services | Food and Drug Administration

. . . . . . . 26

Department of Homeland Security

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Department of Justice

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Department of State

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Executive Oce of the President | United States Trade Representative

. . . . . . . . . . 32

The Library of Congress | The Copyright Oce

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Agencies’ 2010 Major Intellectual Property Enforcement Activities to Date . . . . . . . . . 35

Department of Agriculture

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Department of Commerce

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Department of Health and Human Services | Food and Drug Administration

. . . . . . . 38

Department of Homeland Security

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Department of Justice

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

ii

★ ★

Department of State . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Executive Oce of the President | United States Trade Representative

. . . . . . . . . . 44

The Library of Congress | The Copyright Oce

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Performance Measures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Performance Measures: Data, Measures, and Indicators

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Appendix 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

History of the IPEC Oce and Process Leading to this Joint Strategic Plan

. . . . . . . . 49

Appendix 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Literature Review

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Appendix 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

List of Acronyms

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Letter to the President of the United

States and to the Congress

I am pleased to transmit the 2010 Joint Strategic Plan on Intellectual Property Enforcement.

Intellectual property laws and rights provide certainty and predictability for consumers and producers

in the exchange of innovative and creative products, and for investors shifting capital to their develop-

ment. Where there are insucient resources, ability, or political will to appropriately enforce these rights,

exchanges between investors, producers and consumers may be inecient, corrupt or even dangerous.

Our entrepreneurial spirit, creativity and ingenuity are clear comparative advantages for America in the

global economy. As such, Americans are global leaders in the production of creative and innovative

services and products, including digital content, many of which are dependent on the protection of

intellectual property rights. In order to continue to lead, succeed and prosper in the global economy,

we must ensure the strong enforcement of American intellectual property rights.

The Prioritizing Resources and Organization for Intellectual Property Act (PRO-IP Act) directs the

Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator (IPEC) to coordinate the development of a Joint Strategic

Plan against counterfeiting and infringement. To prepare this Joint Strategic Plan, my oce worked

closely across numerous Federal agencies and departments and with signicant input from the public.

We heard from a broad array of Americans and received more than 1,600 public comments with spe-

cic and creative suggestions. Federal agencies, including the U.S. Departments of Agriculture (USDA),

Commerce (DOC), Health and Human Services (HHS), Homeland Security (DHS), Justice (DOJ), and State

(DOS), the Oce of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the U.S. Copyright Oce participated in

the development of this Joint Strategic Plan. An appendix to this Joint Strategic Plan further details

public and government input.

Through this process, we identied a number of actions the Federal government will take to enhance

the protection of American intellectual property rights:

1. We will lead by example and will work to ensure that the Federal government does not purchase

or use infringing products.

2. We will support transparency in the development of enforcement policy, information sharing

and reporting of law enforcement activities at home and abroad.

3. We will improve coordination and thereby increase the eciency and eectiveness of law

enforcement eorts at the Federal, state and local level, of personnel stationed overseas and

of the U.S. Government’s international training eorts.

4. We will work with our trading partners and with international organizations to better enforce

American intellectual property rights in the global economy.

5. We will secure supply chains to stem the ow of infringing products at our borders and through

enhanced cooperation with the private sector.

6. We will improve data and information collection from intellectual property-related activity and

continuously assess domestic and foreign laws and enforcement activities to maintain an open,

fair and balanced environment for American intellectual property rightholders.

I look forward to continuing to work with you, with the Federal agencies and with the public to improve

enforcement of American intellectual property rights.

Victoria A. Espinel

U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator

3

★ ★

Introduction

“[W]e’re going to aggressively protect our intellectual property. Our

single greatest asset is the innovation and the ingenuity and creativity

of the American people. It is essential to our prosperity and it will only

become more so in this century.”

—President Barack Obama, March 11, 2010

Americans work daily to create a better world. We create products and services that improve the world’s

ability to communicate, to learn, to understand diverse cultures and beliefs, to be mobile, to live better

and longer lives, to produce and consume energy eciently and to secure food, nourishment and safety.

Most of the value of this work is intangible—it lies in America’s entrepreneurial spirit, our creativity,

ingenuity and insistence on progress and in creating a better life for our communities and for communi-

ties around the world. These intangible assets, often captured as copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade

secrets and other forms of “intellectual property,” reect America’s advantage in the global economy.

The U.S. Government supports strengthened enforcement of intellectual property rights for a number

of reasons:

Growth of the U.S. economy, creation of jobs for American workers and support for

U.S. exports

Enforcement of intellectual property rights is a critical and ecient tool we can use, as a gov-

ernment, to strengthen the economy, support jobs and promote exports. Intellectual property

supports jobs across all industries, and in particular where there is a high degree of creativity,

research and innovation: good jobs, with high wages and strong benets. Intellectual property-

related industries can employ an engineer working for a technology company to design the

next generation of cell phones, a software developer writing a new algorithm to improve search

engine results, a chemist working for a pharmaceutical company to develop a new drug, a union

member helping to manufacture a newly-designed tire for automobiles, or a camera operator

working on a movie set to help lm the next Oscar-winning movie. Eective enforcement of

intellectual property rights throughout the world will help Americans export more, grow our

economy and sustain good jobs for American workers.

Promotion of innovation and security of America’s comparative advantage in the global

economy

This Administration believes strongly that promoting innovation is critical to the continued suc-

cess of our nation, to addressing global challenges and to providing peace, safety and prosperity

for our communities. Our ability to continue to lead as a creative, innovative and productive

engine for global benet is compromised by those countries who, for their own narrow and

short-term benet, fail to enforce the rule of law, our agreements with them or adopt policies

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

4

★ ★

that create unfair markets. Americans should not face inappropriate competition from foreign

companies based on advantages arising or derived from insucient protection of intellectual

property rights. Strong enforcement of intellectual property rights is an essential part of the

Administration’s eorts to promote innovation and ensure that the U.S. is a global leader in

creative and innovative industries.

Protection of consumer trust and safety

Violations of intellectual property rights, ambiguities in law and lack of enforcement create

uncertainty in the marketplace, in the legal system and undermine consumer trust. Supply

chains become polluted with counterfeit goods. Consumers are uncertain about what types of

behavior are appropriate and whether the goods they are buying are legal and safe. Counterfeit

products can pose a significant risk to public health, such as toothpaste with dangerous

amounts of diethylene glycol (a chemical used in brake uid), military systems with untested

and ineective components to protect U.S. and allied soldiers, auto parts of unknown quality

that play critical roles in securing passengers and suspect semiconductors used in life-saving

debrillators. Protecting intellectual property rights, consistent with our international obliga-

tions, ensures adherence and compliance with numerous public health and safety regulations

designed to protect our communities.

National and economic security

Intellectual property infringement can undermine our national and economic security. This

includes counterfeit products entering the supply chain of the U.S. military, and economic

espionage and theft of trade secrets by foreign citizens and companies. The prot from intel-

lectual property infringement is a strong lure to organized criminal enterprises, which could

use infringement as a revenue source to fund their unlawful activities, including terrorism.

When consumers buy infringing products, including digital content, distributed by or benet-

ing organized crime, they are contributing to nancing their dangerous and illegal activities.

Validation of rights as protected under our Constitution

Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution vests in the Congress the discretion to establish laws

to promote science and artistic creativity “by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors

the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” Over the last two centuries, our

Founding Fathers have been proven right. One of the reasons that the U.S. is a global leader

in innovation and creativity is our early establishment of strong legal mechanisms to provide

necessary economic incentives required to innovate. By the same token, fair use of intellectual

property can support innovation and artistry. Strong intellectual property enforcement eorts

should be focused on stopping those stealing the work of others, not those who are appropri-

ately building upon it.

American industries that depend on intellectual property employ engineers and chemists, artists and

authors, and manufacturers and laborers. As a result, anyone who invests in virtually any enterprise is also

dependent on intellectual property protection. The U.S. is a global leader in developing new technolo-

gies in intellectual property-related industries. From Silicon Valley to Burbank, from Raleigh/Durham’s

IN T RO DUC T ION

5

★ ★

Research Triangle to Boston’s Route 128, we lead the way in bringing new, life-changing pharmaceuti-

cals and medical devices to consumers, developing environmentally-conscious technologies, creating

innovative software products, building new communication networks and producing lms, music and

games craved by consumers throughout the world. However, our leadership in the development of

creative and innovative products and services also makes us a global target for theft.

Combating counterfeiting and piracy requires a robust Federal response. Strong intellectual property

enforcement supports American jobs, protects American ideas and invigorates our economy. Intellectual

property laws provide not only legal protection for creators and consumers, but incentives to encourage

investment in innovation.

Our status as a global innovation leader is compromised by those countries who fail to enforce the rule

of law or international agreements, or who adopt policies that disadvantage American industries. This

Administration is rmly committed to promoting innovation and protecting the creative and innovative

production of the American workforce.

The Internet and other technological innovations have revolutionized society and the way we obtain

information and purchase products. Lowering barriers to entry and creating global distribution chan-

nels, they have opened new markets and opportunities for American exports of information, goods

and services, including enabling small and medium sized businesses to reach consumers worldwide.

These innovations have also facilitated piracy and counterfeiting on a global scale. Counterfeiters have

developed sophisticated distribution networks. Today, the Internet allows for a person who illegally “cam-

cords” a lm at a movie theater in Moscow to distribute a bootleg copy across the globe with the push

of a button. A company in Delhi producing counterfeit pharmaceuticals can instantly create a global

market. Counterfeiters in Shenzhen making routers and switches can inltrate supply chains in the U.S.

These thieves impose substantial costs. They depress investment in technologies needed to meet global

challenges. They put consumers, families and communities at risk. They unfairly devalue America’s

contribution, hinder our ability to grow our economy, compromise good, high-wage jobs for Americans

and endanger strong and prosperous communities.

So long as the rules and rights for intellectual property are predictable and enforceable, Americans will

continue to lead in the eort to improve global prosperity. There are numerous challenges to meeting

these goals of predictability and enforceability. Our eort must be coordinated, ecient and compre-

hensive. Solutions will require strong and decisive government action, transparency and cooperation

from rightholders, importers, exporters and entities that currently benet from infringement. This Joint

Strategic Plan reects such an eort across our government, our economy and with our trading partners

around the world. The 33 enforcement strategy action items spelled out in the section below represent

the U.S. Government’s coordinated approach to strengthening intellectual property enforcement.

These action items and their implementation are our rst collective step towards our goal of combating

infringement.

7

★ ★

Enforcement Strategy Action Items

As provided by the PRO-IP Act, the IPEC and the Federal agencies responsible for combating intellectual

property infringement have worked together, with signicant input from the public, to identify ways in

which the U.S. Government can enhance intellectual property enforcement. See Appendix 1 (further

describing the process). The results are the 33 enforcement strategy action items spelled out below,

which will shape the coordinated ght to combat intellectual property infringement. Those action

items fall within six categories of focus for the U.S.: (1) leading by example; (2) increasing transparency;

(3) ensuring eciency and coordination; (4) enforcing our rights internationally; (5) securing our supply

chain; and (6) building a data-driven Government.

Leading By Example

First, the U.S. Government cannot eectively ask others to act if we will not act ourselves. To that end,

the U.S. Government will lead by example and will work to ensure that the Federal government does

not purchase or use infringing products.

Establishment of a U.S. Government-Wide Working Group to Prevent U.S. Government Purchase

of Counterfeit Products

The U.S. Government shall establish a government-wide working group tasked with studying how

to reduce the risk of the procurement of counterfeit parts by the U.S. Government. Although the

Government Accountability Oce (GAO) recently issued a report identifying deciencies in the procure-

ment process practices and policies with regard to one government agency, all government agencies

would benet from a review of such policies and practices. The IPEC will convene this working group,

whose members will include the National Security Council (NSC), Department of Defense (DOD)/

Acquisition, Technology and Logistics (AT&L), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA),

General Services Administration (GSA), DOC, Small Business Administration (SBA), DHS, and other partici-

pants as may be identied by the IPEC. The working group shall be led by the IPEC, the Administrators of

GSA and Federal Procurement Policy, and the Undersecretary of Defense for AT&L at DOD. The working

group shall submit to the President, within 180 days after its rst meeting, a memorandum outlining

its ndings and issues requiring further analysis.

Use of Legal Software by Federal Contractors

Executive Order 13103, issued by President Clinton on September 30, 1998, requires that Federal agen-

cies take steps to ensure that they use only legal copies of software. However, this prohibition on the

illegal use of software does not apply equally to government contractors. The Executive Order provides

for contractor certication only if the agency discovers that the contractor is using Federal funds directly

to buy or maintain illegal software. To demonstrate the importance we place on the use of legal software

and to set an example to our trading partners, the U.S. Government will review its practices and policies

to promote the use of only legal software by contractors.

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

8

★ ★

Increasing Transparency

Second, information and information sharing are critical to eective enforcement. The U.S. Government

will thus support transparency in the development of enforcement policy; information sharing with,

from and among federal agencies (including law enforcement agencies); and reporting of enforcement

activities at home and abroad.

Improved Transparency in Intellectual Property Policy-Making and International Negotiations

The Administration supports improved transparency in intellectual property enforcement policy-making

and international negotiations. As such, the U.S. Government will enhance public engagement through

online outreach, stakeholder outreach, congressional consultations and soliciting feedback through

advisory committees, ocial comment mechanisms such as Federal Register notices (FRN), notices of

proposed rulemaking (NPRM) and notices of inquiry (NOI), as appropriate for the relevant process. In

the context of trade negotiations, the Administration will pursue these objectives consistently with the

approaches and considerations set out in the President’s 2010 Trade Policy Agenda, including consid-

eration of the need for condentiality in international trade negotiations to facilitate the negotiation

process.

Increased Information Sharing with Rightholders

As the quality of counterfeit and pirated products improves, it is becoming increasingly dicult for law

enforcement ocials to distinguish counterfeit or pirated goods from genuine products. Rightholders

are particularly well equipped to identify the legitimacy of their own goods, through various methods,

including production coding. Sharing of information between U.S. Government enforcement agencies

and rightholders is therefore helpful in order to make accurate infringement determinations.

Similarly, sharing samples of circumvention devices—devices that would-be-infringers use to defeat

mechanisms put in place to prevent the playing of piratical copies of copyrighted works (a modchip

is a common example of a circumvention device)—would allow rightholders to assist in determining

whether such devices violate an import prohibition. Furthermore, sharing of samples of, and enforce-

ment information on, seized circumvention devices can assist rightholders in their own investigations.

The U.S. Government will take action to provide DHS components with the authority to share informa-

tion and samples of goods and circumvention devices with rightholders before the government seizes

the goods, so that rightholders can assist in accurate determinations of infringement and violation. The

U.S. Government will also take action to provide DHS components with the authority to share samples

and enforcement information related to seized circumvention devices to strengthen criminal and civil

enforcement.

The U.S. Government will ensure that appropriate safeguards are implemented to protect personally

identiable information, including compliance with the Privacy Act, as warranted.

Communication with Victims/Rightholders

Infringement of intellectual property rights can happen to small businesses or other entities or people

on a single occasion or, unlike some other types of crimes, it can also happen to the same victim on a

ENF O RC EM EN T S TRAT E GY AC TIO N I TEMS

9

★ ★

repeated basis. The U.S. Government will work to help victims/rightholders understand: (1) how to report

a potential intellectual property crime; (2) the types of intellectual property cases generally accepted by

the U.S. Government for prosecution; and (3) the types of information that victims/rightholders should

provide when referring an intellectual property case for prosecution. The U.S. Government will have

ongoing communication with victims/rightholders during criminal investigations, as permitted by the

Government’s legal, ethical and law enforcement obligations.

Reporting on Best Practices of Our Trading Partners

Although lack of adequate enforcement remains a problem around the world, individual countries

have adopted laws or practices that have led to signicant improvements in intellectual property

enforcement. While the U.S. needs to continue to raise concerns where they exist, we should also draw

attention to progress made by other countries, including their most eective policies and successful

law enforcement programs. The U.S. Government will report on progress made in other countries and

note specic best practices adopted by those countries. This will serve to commend their eorts and

underscore their leadership example.

Identify Foreign Pirate Websites as Part of the Special 301 Process

Included in USTR’s annual Special 301 report is the Notorious Markets list, a compilation of examples

of Internet and physical markets that have been the subject of enforcement action or that may merit

further investigation for possible intellectual property infringements. While the list does not represent

a nding of violation of law, but rather is a summary of information USTR reviewed during the Special

301 process, it serves as a useful tool to highlight certain marketplaces that deal in infringing goods and

help sustain global piracy and counterfeiting.

USTR will continue to publish the Notorious Markets list as part of its annual Special 301 process.

Additionally, USTR, in coordination with the IPEC, will initiate an interagency process to assess oppor-

tunities to further publicize and potentially expand on the list in an eort to increase public awareness

and guide related trade enforcement actions.

Tracking and Reporting of Enforcement Activities

DOJ reports the number of prosecutions of intellectual property infringers and DHS reports the number

of seizures of infringing products. In addition, under the PRO-IP Act, DOJ and the Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI) submit annual reports to Congress detailing enforcement activities. In order to provide

comprehensive information about the scope of intellectual property enforcement activities, DOJ and

DHS will track and report on enforcement activities related to circumvention devices.

Sharing of Exclusion Order Enforcement Data

Under Section 337 of the Tari Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. § 1337), the International Trade Commission (ITC)

is responsible for investigating allegations regarding unfair practices in import trade, including those

related to intellectual property infringements. Once the ITC makes a determination of infringement, it

issues a Section 337 exclusion order and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) bars the importation of

infringing goods.

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

10

★ ★

More robust information sharing between CBP and rightholders would enhance CBP’s eective enforce-

ment of exclusion orders, as well as provide transparency to rightholders. The U.S. Government will seek

changes to provide CBP with the authority to share enforcement data with complainant rightholders,

including denials of entry, seizures pursuant to seizure and forfeiture orders and determinations pursu-

ant to an ITC exclusion order.

Enhanced Communications to Strengthen Section 337 Enforcement

Under Section 337 of the Tari Act of 1930, the ITC investigates allegations regarding unfair practices

in import trade, including allegations related to intellectual property infringement, as well as other

forms of unfair competition. Once the ITC nds a violation of Section 337 and issues an exclusion order

barring the importation of infringing goods, CBP and the ITC are responsible for determining whether

imported articles fall within the scope of the exclusion order. In certain cases, this requires a determina-

tion of whether an article has been successfully redesigned to no longer infringe the right addressed

in the exclusion order and therefore would no longer be denied entry. Determinations of this kind are

often initiated at the request of a manufacturer, importer or other interested party and are conducted

through ex parte

procedures.

Because the parties involved in the original ITC investigation can provide useful information related

to the scope of the intellectual property rights being adjudicated, any determinations subsequent to

the issuance of an ITC exclusion order should involve the parties and, where appropriate, the ITC. To

strengthen Section 337 as an intellectual property enforcement mechanism, the ITC and CBP will explore

procedures to facilitate and encourage communications between CBP and the ITC with respect to the

scope of the exclusion order. This would include current CBP-ITC communication during the investiga-

tion phase. Furthermore, CBP will consider initiatives to enhance the eciency and transparency of the

exclusion order enforcement process, including such possible solutions as the development of an inter

partes proceeding that will involve relevant private parties to the ITC investigation.

Ensuring Eciency and Coordination

Third, to increase efficiency and effectiveness and to minimize duplication and waste, the U.S.

Government will strengthen the coordination of: (1) law enforcement eorts at the Federal, state and

local level; (2) personnel stationed overseas; and (3) international training and capacity building eorts.

Coordination of National Law Enforcement Eorts to Avoid Duplication and Waste

Numerous Federal law enforcement agencies are charged with investigating criminal intellectual

property violations. To avoid duplication and waste and to benet from the specialized expertise of

particular agencies, the IPEC will work with Federal agencies and the National Intellectual Property

Rights Coordination Center (IPR Center) to ensure coordination and cooperation, including:

1.

Breadth of Cooperative Eorts: The U.S. Government will ensure the broad participation of

Federal agencies responsible for criminal intellectual property infringement investigations in

cooperative eorts. To date, one of the largest cooperative eorts is the IPR Center, which was

established by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In alphabetical order, the enti-

ENF O RC EM EN T S TRAT E GY AC TIO N I TEMS

11

★ ★

ties that participate in the IPR Center include CBP, the Defense Criminal Investigative Service

(“DCIS”), DOC International Trade Administration (ITA) and U.S. Patent and Trademark Oce

(“USPTO”), the FBI, the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Oce of Criminal Investigations

(OCI), GSA—Oce of Inspector General, ICE, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (“NCIS”),

and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service (“USPIS”). The IPEC, in coordination with relevant Federal

agencies, will work to ensure the breadth of cooperative eorts, such as those taking place

at the IPR Center. As part of any such cooperative eort, law enforcement agencies will share

information learned from their investigations that may aid others, such as emerging criminal

trends and new infringing technologies, unless such information sharing is prohibited by law

or regulation.

2. Shared Database: The U.S. Government will have a database—or a combination of databases

serving the same function as a single database—that: (1) is shared by Federal law enforcement

agencies; (2) contains information about intellectual property cases; and (3) can provide case-

specic information about pending investigations, including the name and contact informa-

tion for the lead investigative agent. To satisfy this requirement, the U.S. Government can use

or expand existing databases, such as those used by the Organized Crime Intelligence and

Operations Center (IOC-2) and the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF)

Fusion Center, the IPR Center, or Regional Information Sharing Systems (RISS) Safe. All Federal

agencies with responsibility for discovering and/or investigating intellectual property crimes

will contribute their case information to the database(s). The database(s) need not include sensi-

tive intellectual property information, such as national security information, trade secrets, or

grand jury information that cannot be disclosed under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 6(e),

nor information otherwise prohibited by law or regulation. This information sharing will assist

Federal law enforcement in ensuring that appropriate resources are dedicated to investigations

of the highest priority targets.

3. De-coniction: Federal agencies will develop protocols to determine if another agency (or

another oce or component of the same agency) is already investigating a matter—a process

generally called de-coniction—and, where appropriate, Federal agencies will conduct joint

investigations to maximize U.S. Government resources or conduct investigations by a single

agency (or oce or component of an agency) to minimize duplication and waste of resources.

Federal agencies should use databases or clearinghouses—such as those mentioned above—to

de-conict cases.

Coordination of Federal, State and Local Law Enforcement

The U.S. Government has leveraged groups composed of Federal, state and local law enforcement to

address, among other crimes, narcotics tracking, human tracking and terrorism. Such coordination

of prosecution eorts in intellectual property crime cases will allow law enforcement to benet from

the dierent expertise and experiences of the various Federal agencies, of Federal, state and local law

enforcement and of particular prosecutorial oces. Such coordination will also reduce duplication of

resources and conicts among Federal law enforcement agencies and between Federal and state/local

law enforcement. Examples of such coordinated eorts include the 22 Federal, state and local Intellectual

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

12

★ ★

Property Theft Enforcement Teams (“IPTETs”) ICE recently established around the country to combat

intellectual property infringement. DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) has also recently funded a

number of state and local intellectual property task forces that collaborate with Federal law enforcement.

To continue and expand these eorts, the Federal agencies responsible for discovering and/or investigat-

ing intellectual property crimes including, but not limited to, CBP, the FBI, and ICE will work together in

local/regional working groups to coordinate their intellectual property enforcement eorts with each

other and with the United States Attorneys’ Oces, as appropriate, as least in localities or regions where

intellectual property infringement is most prevalent. The U.S. Government will encourage state and local

law enforcement and prosecutors responsible for intellectual property enforcement to participate in

these working groups.

Coordination of Training for State and Local Law Enforcement and Prosecutors

The U.S. Government will provide training to interested state and local law enforcement and prosecutors

on intellectual property enforcement. Federal agencies will work with each other and with state and

local law enforcement organizations and non-prot entities—including the National White Collar Crime

Center (“NW3C”) and the National Association of Attorneys General (“NAAG”)—to coordinate eorts to

develop materials for such training and to provide such training.

Improve the Eectiveness of Personnel Stationed Overseas to Combat Intellectual Property

Infringement

Combating intellectual property infringement overseas is a priority for the Administration because of

its eect on jobs, the U.S. economy and threats to health and public safety. It is critical that we station

overseas personnel in countries of concern to ensure intellectual property is made a priority. It is also

critical that we ensure that overseas personnel receive clear guidance on the Administration’s overall

enforcement priorities. Thus, to improve the eectiveness of these personnel with regard to protecting

intellectual property rights, the U.S. Government will take the following steps:

1. prioritize stationing of all overseas personnel trained to address intellectual property enforce-

ment based on an assessment by the U.S. Government of the need to address intellectual

property enforcement issues in particular countries or regions;

2. prioritize stationing of additional law enforcement personnel with significant intellectual

property enforcement responsibilities overseas;

3. develop intellectual property enforcement work plans for appropriate embassy personnel to

follow in all countries in which intellectual property enforcement is a priority;

4. establish or enhance working groups within embassies to implement embassy intellectual

property enforcement work plans in priority countries;

5. strengthen regular coordinated communication between personnel stationed overseas and

the agency headquarters to ensure U.S. government personnel stationed overseas have a clear

sense of priorities and guidance; and

ENF O RC EM EN T S TRAT E GY AC TIO N I TEMS

13

★ ★

6. introduce and implement procedures to measure the eectiveness of overseas personnel in

addressing identied intellectual property enforcement issues.

Coordination of International Capacity Building and Training

The U.S. Government has undertaken substantial eorts to reduce intellectual property infringement

internationally through capacity-building exercises including seminars, workshops, outreach programs

and training programs designed to educate foreign governments, citizens and private sector stakehold-

ers on the need and mechanisms for strengthening intellectual property protection, and to provide the

tools for eective enforcement of intellectual property. However, these eorts could be more eective

if existing coordination was strengthened.

In order to increase coordination and to promote ecient use of U.S. Government resources, the U.S.

Government will:

1. to strengthen interagency coordination of international capacity building and training, establish

an interagency committee through which agencies will share plans, information and best prac-

tices and also integrate coordination of capacity building eorts with interagency coordination

of overall development assistance to developing countries;

2. focus capacity building and training eorts in those countries in which intellectual property

enforcement is a high priority and where those eorts can be most eective;

3. develop comprehensive needs assessments and, based on those assessments, develop agency

strategic plans for capacity building in the coming years;

4. establish mechanisms to evaluate the eectiveness of capacity building and training programs;

5. deposit international intellectual property enforcement training materials or catalogs in a shared

database so that all agencies have access to them to promote greater consistency and to avoid

duplication and waste of resources;

6.

ensure that training and capacity building materials are consistent with U.S. intellectual property

laws and policy goals;

7.

ensure that training oered by the U.S. Government on U.S. copyright law includes an explana-

tion of the relevant balance provided in U.S. law between a creator’s rights in his or her work

and specically dened legal limitations on those rights; and

8. coordinate training eorts with international organizations and the business community to

make training more ecient.

Establishment of a Counterfeit Pharmaceutical Interagency Committee

The IPEC shall establish an interagency committee on the counterfeiting of pharmaceutical drugs

and medical products. This committee will bring together the expertise of numerous Federal agen-

cies, including the Oce of National Drug Control Policy, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DOC,

DOS/U.S. Agency of International Development (USAID), HHS/FDA, the IPR Center, CBP, ICE, FBI, the Drug

Enforcement Administration (DEA), USTR, and Veterans Aairs. The committee will invite experts from the

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

14

★ ★

private sector to participate as needed, and in full compliance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act

and other relevant Federal laws and regulations. Among other issues, the committee shall examine the

myriad of problems associated with unlicensed Internet pharmacies, health and safety risks in the U.S.

associated with the distribution of counterfeits and the proliferation of the distribution of counterfeit

pharmaceuticals in Africa. The IPEC shall chair the committee. The committee shall produce a report

with specic recommendations for government action within 120 days of the commencement of its

rst meeting.

Enforcing Our Rights Internationally

Fourth, addressing infringement in other countries is a critical component of protecting and enforcing

our rights. To that end, the U.S. Government will work collectively to strengthen enforcement of intel-

lectual property rights internationally.

Combat Foreign-Based and Foreign-Controlled Websites that Infringe American Intellectual

Property Rights

The use of foreign-based and foreign-controlled websites and web services to infringe American intel-

lectual property rights is a growing problem that undermines our national security, particularly our

national economic security. Despite the scope and increasing prevalence of such sites, enforcement is

complicated because of the limits of the U.S. Government’s jurisdiction and resources in foreign coun-

tries. To help better address these enforcement issues, Federal agencies, in coordination with the IPEC,

will expeditiously assess current eorts to combat such sites and will develop a coordinated and com-

prehensive plan to address them that includes: (1) U.S. law enforcement agencies vigorously enforcing

intellectual property laws; (2) U.S. diplomatic and economic agencies working with foreign governments

and international organizations; and (3) the U.S. Government working with the private sector.

Enhance Foreign Law Enforcement Cooperation

International law enforcement cooperation is a critical part of combating the global nature of piracy

and counterfeiting. Federal law enforcement agencies will encourage cooperation with their foreign

counterparts to: (1) enhance eorts to pursue domestic investigations of foreign intellectual property

infringers; (2) encourage foreign law enforcement to pursue those targets themselves; and (3) increase

the number of criminal enforcement actions against intellectual property infringers in foreign countries

in general. Federal law enforcement agencies will also use, as appropriate, formal cooperative agree-

ments or arrangements with foreign governments as a tool to strengthen cross-border intellectual

property enforcement eorts.

Promote Enforcement of U.S. Intellectual Property Rights through Trade Policy Tools

The U.S. Government has traditionally sought to use the tools of trade policy to seek strong intellectual

property enforcement. Examples include bilateral trade dialogues and problem-solving, communicating

U.S. concerns clearly through reports such as the Special 301 Report, committing our trading partners

to protect American intellectual property through trade agreements such as the Anti-Counterfeiting

Trade Agreement (ACTA) and the Trans-Pacic Partnership (TPP), and, when necessary, asserting our

ENF O RC EM EN T S TRAT E GY AC TIO N I TEMS

15

★ ★

rights through the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement process. USTR, in coordination

with the IPEC and relevant Federal agencies, will continue the practice of using these tools to seek

robust intellectual property enforcement, including protection of patents, copyrights, trade secrets and

trademarks including geographical indications, as well as strong civil, criminal and border measures.

Furthermore, USTR will be vigilant in enforcing U.S. trade rights under its trade agreements. These eorts

will be conducted in a manner consistent with the balance found in U.S. law and the legal traditions of

U.S. trading partners.

Special 301 “Action Plans”

USTR conducts annual reviews of intellectual property protection and market access practices in foreign

countries. Through an extensive Special 301 interagency process, USTR publishes a report annually,

designating countries of concern on dierent watch lists, referred to as “priority watch list” (PWL), “watch

list” and “priority foreign country.” Countries placed on the PWL are the focus of increased bilateral atten-

tion concerning the problem areas. The 2010 Special 301 report countries on the PWL included Algeria,

Argentina, Canada, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Russia, Thailand and Venezuela.

USTR also develops action plans and similar documents to establish benchmarks, such as legislative,

policy or regulatory action, and as a tool to encourage improvements by countries in order to be

removed from the Special 301 list. In order to work with foreign governments to improve their practices

related to intellectual property and market access, USTR, in coordination with the IPEC, will initiate an

interagency process to increase the eectiveness of, and strengthen implementation of, Special 301

action plans. The action plans, or other appropriate measures, will focus on selected trading partners

for which targeted eorts could produce desired results.

Strengthen Intellectual Property Enforcement through International Organizations

Numerous international organizations have an interest in and focus on intellectual property rights. The

IPEC will work with relevant Federal agencies and the IPR Center to raise awareness of intellectual prop-

erty enforcement and to increase international collaborative eorts through international organizations,

such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the WTO, the World Customs Organization

(WCO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Group of Twenty Finance Ministers and Central Bank

Governors (G-20), the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), the Asia-Pacic Economic

Cooperation (APEC) Forum, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

By working with such organizations, the U.S. Government can strengthen international intellectual

property enforcement eorts and increase cross-border diplomatic and law enforcement cooperation.

In particular, the U.S. Government will explore opportunities for joint training, sharing of best practices

and lessons learned and coordinated law enforcement action.

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

16

★ ★

Securing Our Supply Chain

Fifth, the U.S. Government will work to secure supply chains to stem the ow of infringing products

through law enforcement eorts and through enhanced cooperation with the private sector.

FDA Notication Requirement for Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals and Other Medical Products

Because of the serious risk to public health, manufacturers and importers shall be required to notify the

FDA in the event of a known counterfeit of any pharmaceutical and other medical product. The required

notication shall also specify any known potential adverse health consequences of the counterfeit prod-

uct. Drug manufacturers shall also be required to provide the FDA with a list and complete description

of any legitimate drug products that are currently being distributed in the stream of U.S. commerce on a

twice annual basis, so that the FDA has updated information on all drugs and medical devices currently

being sold by the manufacturer. This could be eectuated by amending 21 U.S.C. Section 331.

Mandated Use of Electronic Track and Trace for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Products

The Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act should be modied to require that manufacturers, wholesalers and

dispensers implement a track-and-trace system, which allows for authentication of the product and

creation of an electronic pedigree for medical products using unique identiers for products. Eective

track-and-trace systems can make it more dicult for persons to introduce counterfeit or intentionally

adulterated medical products into the U.S. market, make it easier to identify persons responsible for

making a product unsafe and facilitate the recall of unsafe products by more quickly identifying where

a product is located in the marketplace. Privacy concerns will be considered when deciding where the

information will be housed and who will have access to the information.

Increased Enforcement Eorts to Guard Against the Proliferation of Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals

and Medical Devices

In an eort to further secure our supply chains, and to help stop the proliferation of counterfeit phar-

maceuticals and medical devices in the stream of commerce, increased U.S. Government action is

warranted. The IPEC will therefore work with relevant Federal agencies, including DHS (CBP and ICE)

and HHS/FDA, to establish increased enforcement cooperation, coordination and information sharing

consistent with current agreements, procedures, notices, alerts, guidance, memoranda of understanding

and established partnerships for daily operations at U.S. borders. To further these eorts, the IPEC will

work with these agencies to make certain that they have the enforcement authority that they need to

address the problems associated with counterfeit pharmaceuticals and medical devices.

Penalty Relief for Voluntary Disclosure

In cases where importers or other parties discover that they have acquired counterfeit or pirated prod-

ucts without their knowledge, there is no existing process by which the importers can voluntarily disclose

violations to CBP without being subject to seizures and other enforcement actions. In order to discover

counterfeit goods, encourage voluntary disclosure and strengthen cooperation between industry and

enforcement entities, the U.S. Government will take action to allow importers and others involved in the

importation of infringing goods to receive relief from civil enforcement action as appropriate when they

ENF O RC EM EN T S TRAT E GY AC TIO N I TEMS

17

★ ★

voluntarily disclose the violation to CBP prior to the beginning of an investigation. If a valid disclosure

is made, the infringing goods in the disclosing party’s possession or control would be destroyed under

CBP’s supervision and the disclosing party would bear the costs of destruction.

Penalize Exporters of Infringing Goods

While CBP has seizure and forfeiture authority related to the exportation of intellectual property infring-

ing goods, it does not have express authority to issue administrative penalties on infringing exports. In

order to ensure broader authority to protect U.S. intellectual property across the supply chain, the U.S.

Government will seek legislative amendments to specify authority for CBP to create and implement

a mechanism to evaluate and issue administrative penalties for intellectual property-related export

violations.

Streamline Bonding Requirements for Circumvention Devices

One of the tools available for rightholders to assist CBP in enforcing against counterfeit and pirated

goods is for rightholders to obtain a sample of the suspected product to determine if it is infringing. In

those instances, CBP requires that rightholders post a bond to cover the potential loss or damage to

the sample if the products are ultimately found to be non-infringing. Certain rightholders interact with

CBP frequently in this cooperative manner so posting an individual transaction bond for each sample

can be burdensome.

To streamline this requirement, in October 2009, CBP implemented a continuous bond option for

trademark and copyright infringement cases, allowing rightholders to post a single bond that covers

several transactions at dierent ports of entry. Contingent on CBP obtaining the authority to provide

rightholders samples of circumvention devices and in order to further streamline bonding requirements,

CBP will extend the new bond practice to cover samples of circumvention devices.

Facilitating Cooperation to Reduce Intellectual Property Infringement Occurring Over the

Internet

The U.S. Government supports the free ow of information and freedom of expression over the Internet.

An open and accessible Internet is critical to our economy. At the same time, the Internet should not be

used as a means to further criminal activity. The Administration encourages cooperative eorts within

the business community to reduce Internet piracy. The Administration believes that it is essential for

the private sector, including content owners, Internet service providers, advertising brokers, payment

processors and search engines, to work collaboratively, consistent with the antitrust laws, to address

activity that has a negative economic impact and undermines U.S. businesses, and to seek practical

and ecient solutions to address infringement. This should be achieved through carefully crafted and

balanced agreements. Specically, the Administration encourages actions by the private sector to eec-

tively address repeated acts of infringement, while preserving the norms of legitimate competition, free

speech, fair process and the privacy of users. While the Administration encourages cooperative eorts

within the business community to reduce Internet piracy, the Administration will pursue additional solu-

tions to the problems associated with Internet piracy, including vigorously investigating and prosecuting

criminal activity, where warranted.

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

18

★ ★

Establish and Implement Voluntary Protocols to Help Reduce Illegal Internet Pharmacies

Google, Yahoo and Bing recently updated voluntary protocols designed to prevent the sale of spon-

sored results for unlawful businesses selling counterfeit medications on-line. These protocols utilize a

“White List” of pre-approved Internet pharmaceutical sellers that include verication by the National

Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s Veried Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites (VIPPS) or certications

from the original manufacturers of legitimate and FDA-approved pharmaceuticals. The U.S. Government

applauds these eorts by the private sector and will continue to work with these companies and other

search engine operators, advertising brokers and payment processors to explore methods to prohibit

paid advertising for on-line illegal pharmaceutical vendors. Simultaneously, the U.S. Government will

explore means by which online pharmaceutical companies operating in violation of intellectual property

laws can be made subject to the full reach of law enforcement jurisdiction.

Building a Data-Driven Government

Sixth, information is critical to developing effective enforcement strategies. To that end, the U.S.

Government will improve data and information collection from intellectual property-related activities

and assess domestic and foreign laws and enforcement activities to enable an open and fair environment

for American intellectual property rightholders.

U.S. Government Resources Spent on Intellectual Property Enforcement

Several agencies across the U.S. Government dedicate resources toward the enforcement of intellectual

property. In order to better track resource baselines and inform future resource allocations dedicated

to intellectual property enforcement, the IPEC will collect annually the amount of U.S. Government

resources spent on intellectual property enforcement personnel, technologies, programs and other

eorts.

The IPEC has already begun that process by collecting this information in Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 through

a Budget Data Request (BDR), whereby agencies reported the amount of resources they dedicated to

human capital and programs, identied metrics used in measuring intellectual property enforcement

successes, and planned and estimated expenditures for future years. Moving forward, the IPEC will

continue coordinating this BDR annually, and will request the same data and metrics to allow for cross

and multi-year comparisons.

Assessing the Economic Impact of Intellectual Property-Intensive Industries

There is no known comprehensive study that attempts to measure the economic contributions of intel-

lectual property-intensive industries across all U.S. business sectors. Improved measures of intellectual

property linked with measures of economic performance would help the U.S. Government understand

the role and breadth of intellectual property in the American economy and would inform policy and

resource decisions related to intellectual property enforcement.

To assess the feasibility of improving measures of intellectual property and linking those measures to

economic performance, the Economic and Statistics Administration (ESA) within DOC, in coordination

ENF O RC EM EN T S TRAT E GY AC TIO N I TEMS

19

★ ★

with the IPEC, will convene an interagency meeting with relevant agencies to establish a framework

for conducting this work. Once that framework is established, ESA will test the feasibility of developing

improved intellectual property measures and, if those measures can be developed, they will be linked

to measures of economic performance. The resulting analysis and datasets will then be made public.

Comprehensive Review of Existing Intellectual Property Laws to Determine Needed Legislative

Changes

Due to changes in technology and the growing sophistication of intellectual property violators, the U.S.

Government must ensure that intellectual property laws continue to eectively and comprehensively

combat infringement. The IPEC will initiate and coordinate a process, working with Federal agencies,

to review existing laws—whether they impose criminal and/or civil liability—to ensure that they are

eectively reaching the appropriate range of infringing conduct, including any problems or gaps in

scope due to changes in technologies used by infringers. Federal agencies will also review existing

civil and criminal penalties to ensure that they are providing an eective deterrent to infringement

(including, as to criminal penalties, reviewing the United States Sentencing Guidelines). Finally, Federal

agencies will review enforcement of existing laws to determine if legislative changes are needed to

enhance enforcement eorts. The initial review process will conclude within 120 days from the date of

the submission of this Joint Strategic Plan to Congress. The Administration, coordinated through the

IPEC, will recommend to Congress any proposed legislative changes resulting from this review process.

Supporting U.S. Businesses in Overseas Markets

With the launch of the President’s National Export Initiative, it is an Administration priority to improve

U.S. Government support for U.S. businesses in overseas markets. American exporters face various

barriers to entry into overseas markets including barriers related to intellectual property rights. U.S.

companies may be reluctant to export due to a lack of certainty that innovation, and the intellectual

property rights in that innovation, can be protected. In addition, exporters may not be familiar with the

legal environment in which they need to operate to protect their rights.

In coordination with the IPEC, DOC and other relevant agencies will conduct a comprehensive review

of existing U.S. Government eorts to educate, guide and provide resources to those U.S. businesses

that are:

1. acquiring intellectual property rights in foreign markets;

2. contemplating exporting intellectual property-based products or choosing markets for export;

3. actively entering foreign markets or facing diculties entering foreign markets; and

4.

encountering diculties enforcing their intellectual property rights in foreign markets.

The goal of the review is to increase the scope and eectiveness of existing eorts through improved

coordination of our diplomatic, cooperative, programmatic and other bilateral mechanisms. This eort

will focus in particular, but not exclusively, on the Chinese market.

21

★ ★

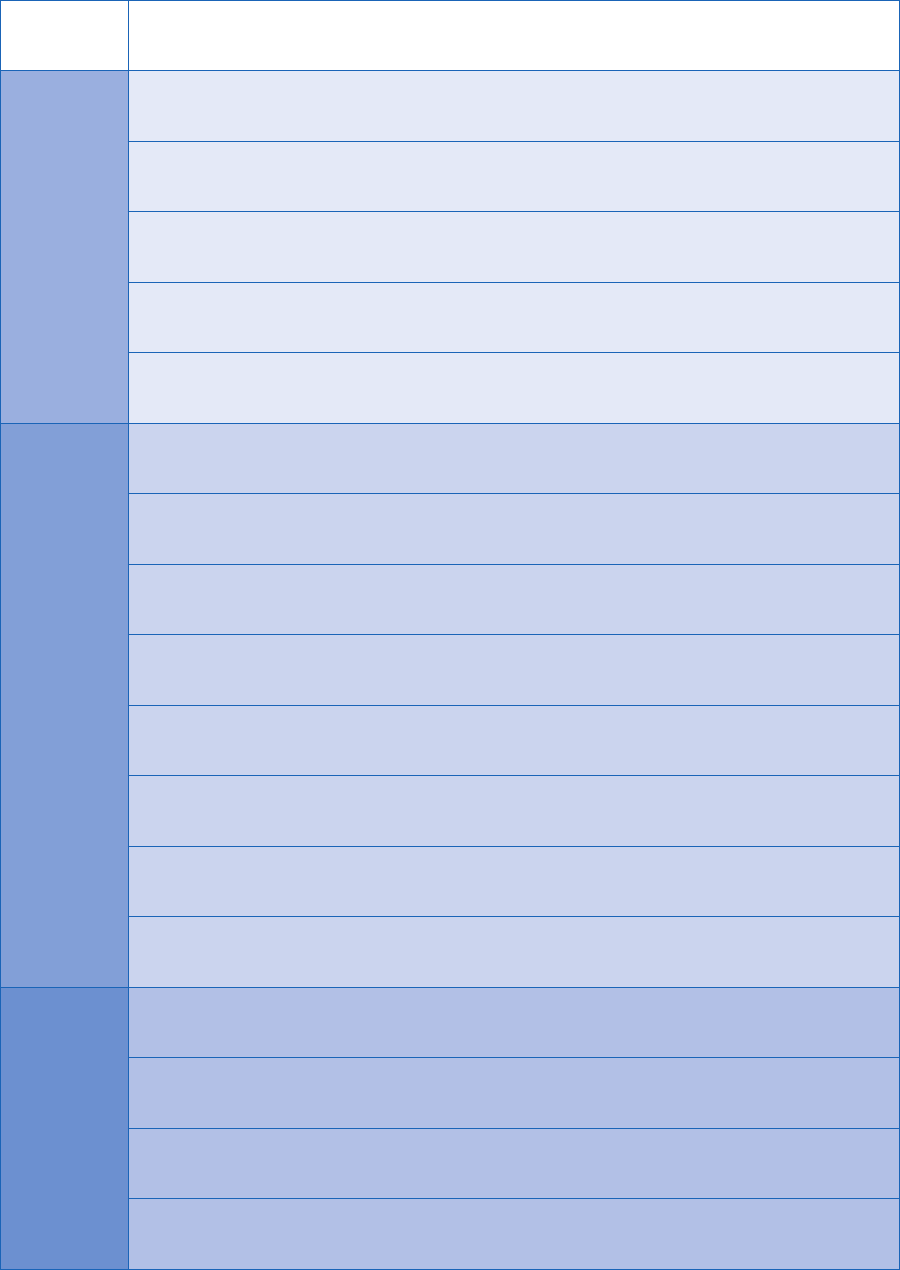

Summary of Enforcement

Strategy Action Items

Action Items

Leading By

Example

Establishment of a U.S. Government-Wide Working Group to Prevent U.S. Government

Purchase of Counterfeit Products

Use of Legal Software by Federal Contractors

Increasing Transparency

Improved Transparency in Intellectual Property Policy-Making and International

Negotiations

Increased Information Sharing with Rightholders

Communication with Victims/Rightholders

Reporting on Best Practices of Our Trading Partners

Identify Foreign Pirate Websites as Part of the Special 301 Process

Tracking and Reporting of Enforcement Activities

Sharing of Exclusion Order Enforcement Data

Enhanced Communications to Strengthen Section 337 Enforcement

Ensuring Eciency

and Coordination

Coordination of National Law Enforcement Eorts to Avoid Duplication and Waste

Coordination of Federal, State and Local Law Enforcement

Coordination of Training for State and Local Law Enforcement and Prosecutors

Improve the Eectiveness of Personnel Stationed Overseas to Combat Intellectual

Property Infringement

Coordination of International Capacity Building and Training

Establishment of a Counterfeit Pharmaceutical Interagency Committee

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

22

★ ★

Action Items

Enforcing Our Rights

Internationally

Combat Foreign-Based and Foreign-Controlled Websites that Infringe American

Intellectual Property Rights

Enhance Foreign Law Enforcement Cooperation

Promote Enforcement of U.S. Intellectual Property Rights through Trade Policy Tools

Special 301 “Action Plans”

Strengthen Intellectual Property Enforcement through International Organizations

Securing Our Supply Chain

FDA Notication Requirement for Counterfeit Pharmaceuticals and Other Medical

Products

Mandated Use of Electronic Track and Trace for Pharmaceuticals and Medical

Products

Increased Enforcement Eorts to Guard Against the Proliferation of Counterfeit

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices

Penalty Relief for Voluntary Disclosure

Penalize Exporters of Infringing Goods

Streamline Bonding Requirements for Circumvention Devices

Facilitating Cooperation to Reduce Intellectual Property Infringement Occurring

Over the Internet

Establish and Implement Voluntary Protocols to Help Reduce Illegal Internet

Pharmacies

Building a Data-Driven

Government

U.S. Government Resources Spent on Intellectual Property Enforcement

Assessing the Economic Impact of Intellectual Property-Intensive Industries

Comprehensive Review of Existing Intellectual Property Laws to Determine Needed

Legislative Changes

Supporting U.S. Businesses in Overseas Markets

23

★ ★

Agencies’ Intellectual Property

Enforcement Missions

Department of Agriculture

USDA supports intellectual property rights enforcement related to agriculture, primarily through the

provision of technical expertise in interagency trade agreement negotiations, dispute resolution and

enforcement mechanisms, and through USDA’s close relationships with the U.S. agricultural industry.

USDA’s support to intellectual property enforcement includes the following:

• Trade Agreements: USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) supports USTR in negotiating,

implementation, and monitoring and enforcement of free trade agreements (FTAs), and inter-

faces with U.S. agricultural industry groups on intellectual property trade agreement issues.

• World Trade Organization: USDA’s FAS supports dispute settlement, accession processes and

negotiations in the WTO related to agriculture.

• Bilateral and Regional Dialogues and Cooperation: USDA’s FAS participates in intellectual

property enforcement discussion in a wide range of trade and economic policy dialogues with

trading partners, and in trade and investment framework agreement discussions. FAS Attachés

overseas and sta in Washington participate in interagency working groups addressing intel-

lectual property issues.

• Coordination of U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Trade Policy: USDA’s FAS participates

in the Special 301 process, an interagency venue for resolving intellectual property policy issues.

Department of Commerce

International Trade Administration

ITA strengthens the competitiveness of U.S. industry, promotes trade and investment and ensures fair

trade through the rigorous enforcement of our trade laws and agreements. As part of its mission, ITA

ensures that our trading partners are fullling their international trade commitments to enforce and

protect intellectual property rights. ITA also responds to inquiries, develops trade programs and tools to

help U.S. businesses and citizens enforce and protect their intellectual property rights in foreign markets,

and conducts outreach to raise awareness.

The Oce of Intellectual Property Rights (OIPR) is responsible for developing and coordinating ITA input

on trade-related intellectual property rights policies, programs and practices and for assisting companies

to overcome challenges to protecting and enforcing their intellectual property rights overseas. The

U.S. Commercial Service, with oces in over 100 U.S. cities and 77 locations abroad, advocates for the

interests of U.S. companies on intellectual property issues with appropriate foreign government ocials,

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

24

★ ★

counsels U.S. companies operating or selling abroad in understanding foreign-country business climates

and legal environments and assists companies to identify in-country resources to assist with registering

and/or protecting their intellectual property rights through administrative or court actions.

As part of an overall strategy to educate the U.S. business community and, in particular, U.S. Small and

Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs), ITA and USPTO, working with other U.S. Government agencies and

the private sector, have developed the www.StopFakes.gov/ website and a number of associated tools

for small businesses. The site includes information on:

• 17 Market-Specic Toolkits, which provide detailed information on protecting U.S. intellectual

property in key markets like China, Brazil and the European Union (EU).

• An online training program developed by OIPR with the Foreign Commercial Service (FCS),

USPTO, and the SBA, for SMEs about evaluating, protecting and enforcing intellectual property

rights (translated into Spanish and French to broaden outreach).

• A program developed by OIPR and the FCS to promote protection of intellectual property rights

at domestic and international trade fairs.

• A program developed with the American Bar Association through which American SMEs can

request a free, one-hour consultation with a volunteer attorney to learn how to protect and

enforce their rights in Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Russia and Thailand.

• The Intellectual Property Protection and Enforcement Manual and the No Trade in Fakes Supply

Chain Tool Kit, which OIPR encouraged the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Coalition Against

Counterfeiting and Piracy (CACP) to develop and release. These documents, posted online at

www.thecacp.com/, showcase proven strategies companies, both small and large, use to protect

their supply chains from counterfeiters and pirates.

Patent and Trademark Oce

USPTO has a long history of encouraging and supporting trading partners, particularly developing and

least developed countries, to move beyond mere adoption of laws protecting intellectual property rights

to the operation of eective systems for enforcement. In 1999, USPTO expanded its technical assistance

and capacity building activities to address intellectual property enforcement. Such capacity building

has included training for foreign government law enforcement ocials, prosecutors, the judiciary and

customs and border enforcement ocials, and technical assistance on drafting laws and regulations

on enforcement-related issues.

USPTO has created a exible team enterprise that meets the challenges of intellectual property enforce-

ment in today’s global economy by: (1) carrying out statutory and international treaty obligations to

assist developing nations in implementing accessible and eective intellectual property enforcement

systems; (2) responding rapidly to changing global and international conditions; (3) establishing alli-

ances with other national and international intellectual property organizations to strengthen, protect

and enforce American intellectual property rights globally; and (4) working with other U.S. Government

agencies, national intellectual property enforcement authorities and international organizations to

AGEN C IES’ IN T ELLECT UA L P RO P ER T Y ENF O RC E M EN T M ISSI ON S

25

★ ★

increase the accessibility, eciency and eectiveness of civil, administrative and criminal enforcement

mechanisms in global trade, foreign markets and electronic commerce.

USPTO regularly consults with foreign governments and other U.S. Government agencies on the sub-

stantive, technical aspects of intellectual property enforcement laws, legal and judicial regimes, civil

and criminal procedures, border measures and administrative regulations relating to enforcement;

advises USTR and DOC on the trade-related aspects of intellectual property enforcement and serves as

technical advisors on enforcement provisions in trade agreements by reviewing, analyzing and monitor-

ing legislative and legal developments pertaining to intellectual property enforcement mechanisms,

administration and public education eorts; develops, conducts, coordinates and participates in training

programs, conferences and seminars, and develops training materials, including long-distance learning

modules, to improve the level of expertise of those responsible for intellectual property enforcement

and the overall enforcement environment; gathers information on and monitors foreign national

enforcement systems, and coordinates intellectual property enforcement-related activities undertaken

by various intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations; and provides technical expertise

on legislation involving intellectual property enforcement.

USPTO’s Global Intellectual Property Academy, established in 2006, is a focal point for intellectual

property rights technical assistance and training, and a crucial component in an integrated approach to

enforcement training and capacity-building, both domestically and internationally. In addition, USPTO

operates the overseas intellectual property Attaché program, which places resident experts in a num-

ber of U.S. missions abroad in order to provide direct, on-the-ground technical expertise, support and

coordination of all intellectual property rights protection and enforcement issues, including training

and capacity-building activities for foreign government ocials.

Commercial Law Development Program

The Commercial Law Development Program (CLDP) improves the legal environment for U.S. businesses

worldwide by removing non-tari barriers to trade and ensuring eective implementation of intellectual

property policies and enforcement provisions. CLDP programs level the playing eld for U.S. industries to

compete in developing markets and provide follow-up support to countries that have limited capacity

to implement some provisions of trade agreements entered into with the U.S. Although CLDP technical

assistance is largely government-to-government, each program is designed to address a pressing need

identied by both local and U.S. businesses.

CLDP partners with other oces within DOC (including USPTO, ITA and National Telecommunications

and Information Administration (NTIA)), as well as DHS, DOJ, DOS/ USAID to provide capacity building

and enforcement technical assistance in developing countries. CLDP’s intellectual property work with

host countries covers drafting legislation, establishing regulations, increasing skills development,

promoting public outreach and ensuring transparency. Many programs address needs across regions

by gathering judiciaries, policy-makers and regulators from multiple countries to share best practices

and develop workable solutions to regional problems related to counterfeiting and piracy. CLDP’s intel-

lectual property work over the years has led to the development of a small library of case studies in a

multitude of languages that include technology transfer, licensing and border measures. These materi-

2010 JOI NT S TRAT EGI C P LA N O N I NTELLE C TUA L P RO PERT Y EN F ORC EM EN T

26

★ ★

als, frequently shared with other U.S. Government partners, are essential learning tools for developing

countries looking to improve intellectual property enforcement.

More information about CLDP’s work and successes related to intellectual property enforcement and

capacity building can be found at

www.cldp.doc.gov.

Department of Health and Human Services | Food and Drug Administration

The FDA is responsible for protecting the public health by assuring the safety and ecacy of medical

products, and the safety of foods. Expanded markets and more complex supply chains have required

the FDA to nd new ways to safeguard global public health. The FDA is acutely aware of the illegality

of and the direct-and-indirect risk posed to the public health by counterfeit medical products, infant

formula and foods that falsely represent their identity and/or source. Those who manufacture and dis-

tribute falsied medical products and foods not only defraud patients and consumers, they also deny ill

patients the medical products that can alleviate suering and save lives and, for a formula that may be

an infant’s sole source of nutrition, the healthy start in life that every child needs. Consequently, the FDA

takes all reports of suspect counterfeits seriously and the FDA’s regulatory ocials have responded to this

emerging threat by: strengthening its ability to prevent the introduction of falsied medical products

and foods into the U.S. distribution chain, facilitating the identication of falsied medical products and

foods, and by minimizing the risk and exposure of patients and consumers to falsied products through

recalls, public awareness campaigns and other steps.

As a part of these eorts, the FDA’s OCI expeditiously investigates reports of suspected falsied products

in order to protect U.S. citizens. Specically, OCI investigates counterfeit products that violate 18 U.S.C.

Section 2320 and 21 U.S.C. Section 331(i). OCI routinely coordinates counterfeit investigations and intel-

ligence with other international, Federal, state and local law enforcement agencies and has initiated

numerous investigations focused on protecting the public health that have led to criminal convictions.

The issue of falsied medical products and food is a global issue that requires a global solution and

the FDA is working with its international regulatory partners to address the public health aspects of

counterfeit medical products and foods. The FDA has also worked with our partners in foreign markets

to strategically establish FDA oces worldwide that help provide technical assistance, among other