Prosecuting Intellectual

Property Crimes

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

By Sally Q. Yates

Department of Justice Task Force on Intellectual

Property: A Coordinated Response to Combat

Intellectual Property Crime . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

By Miriam H. Vogel

Deciding When to Prosecute an Intellectual Property Case . . . . . . . 7

By Christopher S. Merriam and Kendra R. Ervin

Loss Amount in Trade Secret Cases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

By William P. Campos

Prosecuting Copyright Infringement Cases and

Emerging Issues. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

By Jason Gull and Tim Flowers

DOJ’s Strategic Plan for Countering the

Economic Espionage Threat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

By Richard S. Scott and Alan Z. Rozenshtein

IPR Center: Conducting Effective IP Enforcement. . . . . . . . . . . . 27

By Bruce M. Foucart

Operation In Our Sights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

By Justin S. Herring

Prosecuting Counterfeit Prescription Drug Cases. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

By Andrew Lay

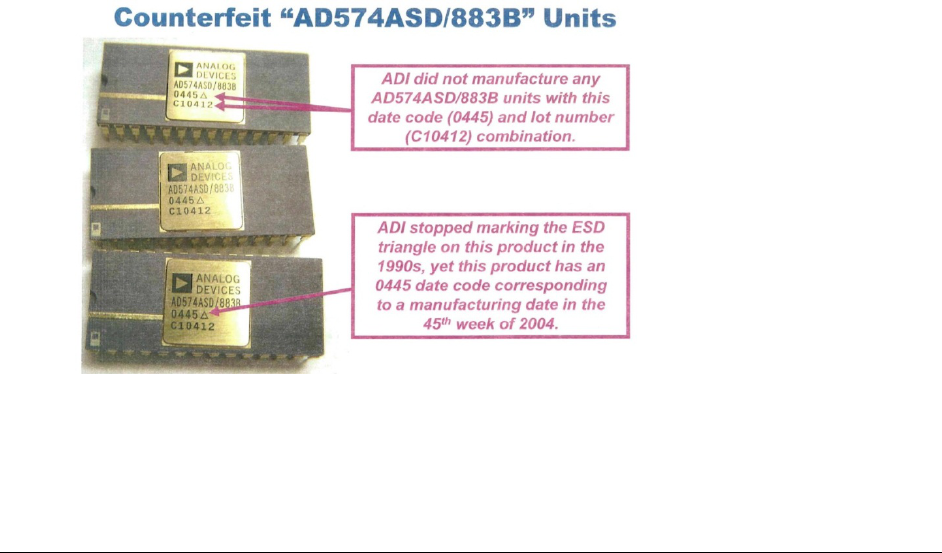

Chipping Away at a Threat to Our Military and National

Security: The Trafficking of Counterfeit Semiconductors. . . . . . . 46

By Edward Chang

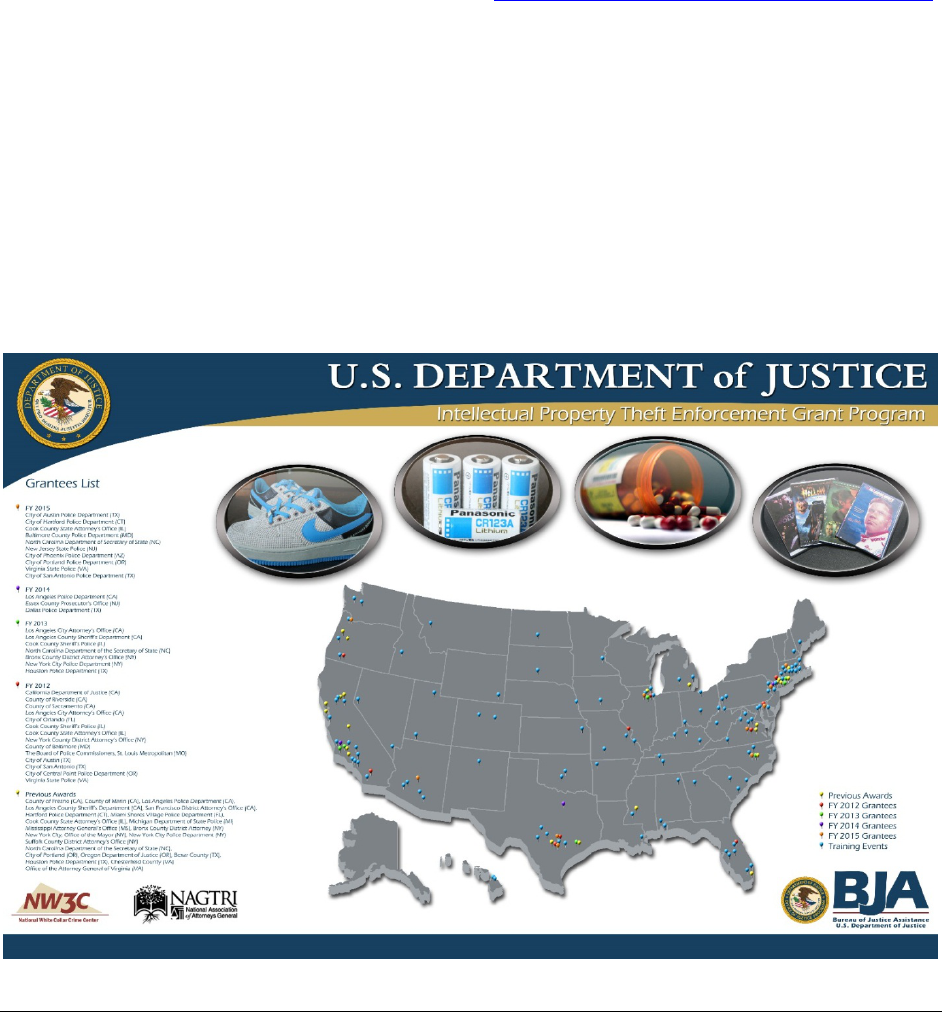

Intellectual Property Enforcement Programs: Helping State and

Local Law Enforcement Combat Intellectual Property Crime . . . 51

By Kristie Brackens

January

2016

Volume 64

Number 1

United States

Department of Justice

Executive Office for

United States Attorneys

Washington, DC

20530

Monty Wilkinson

Director

Contributors’ opinions and statements

should not be considered an

endorsement by EOUSA for any

policy, program, or service.

The United States Attorneys’ Bulletin

is published pursuant to

28 CFR § 0.22(b).

The United States Attorneys’ Bulletin

is published bimonthly by the

Executive Office for United States

Attorneys, Office of Legal Education,

1620 Pendleton Street,

Columbia, South Carolina 29201.

Managing Editor

Jim Donovan

Contractor

Becky Catoe-Aikey

Law Clerk

Mary C. Eldridge

Internet Address

www.usdoj.gov/usao/

reading_room/foiamanuals.

html

Send article submissions

to Managing Editor,

United States Attorneys’ Bulletin,

National Advocacy Center,

Office of Legal Education,

1620 Pendleton Street,

Columbia, SC 29201.

In This Issue

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 1

Introduction

Sally Q. Yates

Deputy Attorney General

U.S. Department of Justice

It is my great pleasure to introduce this edition of the United States Attorneys’ Bulletin devoted to

Intellectual Property (IP). IP crime in the United States and abroad threatens not only our public safety

and economic well-being, but also our national security. Counterfeit products, such as auto parts,

pharmaceuticals, and military equipment can cause death and serious bodily injury. Theft of proprietary

designs, technology, and innovations by competitors can wreak havoc on American industry, creating

unfair market advantages, eroding profits, and causing loss of jobs. Economic espionage by state actors

seeks to harm our national security through attacks on our infrastructure and businesses. Criminals

increasingly use cyber means to carry out these offenses, attempting to become a faceless enemy

committing crimes without attribution. We, as prosecutors, must vigorously defend against these types of

crimes, and continue to utilize all available resources to do so.

As Deputy Attorney General, I serve as the Chair of the Department of Justice Task Force on IP,

composed of senior representatives within the Department. Since its creation in 2010 by then-Attorney

General Eric Holder, the Department’s IP Task Force has confronted this threat with a strong and

coordinated response. Its mission is to support prosecutions in priority areas, provide heightened civil

enforcement, achieve greater coordination among federal, state, and local law enforcement partners, and

increase focus on international enforcement efforts.

Specifically, the Department focuses its efforts to aggressively investigate and prosecute a wide

range of IP crimes, with a particular emphasis on: (1) public health and safety, (2) theft of trade secrets

and economic espionage, and (3) large-scale commercial counterfeiting and piracy. Today our

enforcement efforts at the Department are more vigorous, more strategic, more collaborative, and more

effective than ever before.

This edition of the United States Attorneys’ Bulletin

is the latest resource available to assist

prosecutors in the fight against IP crimes. This issue provides topical guidance and information on IP,

from investigation to sentencing. This

Bulletin contains articles concerning: the IP Task Force and its

function; guidance on prosecuting an IP case; copyright enforcement; the Department’s strategy on

countering economic espionage; the National IP Rights Center led by U.S. Immigration and Customs

Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations; the IP enforcement programs of the Office of Justice

Programs; sentencing considerations; and articles providing case examples in the prosecution of

counterfeit prescription drugs, counterfeit semiconductors, and online commercial counterfeiting

operations.

I encourage each of you to work with your fellow prosecutors and law enforcement partners to

participate in the Department’s multi-faceted approach to combatting this type of crime. It is through your

leadership and vigilance as prosecutors that we will continue to effectively stay ahead of the ever-

adapting threat of IP crime.

2 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

Department of Justice Task Force on

Intellectual Property: A Coordinated

Response to Combat Intellectual

Property Crime

Miriam H. Vogel

Associate Deputy Attorney General

United States Department of Justice

“[P]rotecting the nation’s intellectual property is a vital part of the Justice Department’s mission.”

Remarks by Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch at MassChallenge Roundtable Discussion, Oct. 2, 2015,

available at

http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-loretta-e-lynch-announces-new-

intellectual -property-enforcement-program.

I. Introduction

Why does the Department of Justice focus its leadership efforts and precious resources on

intellectual property (IP) crime? The Department is keenly aware that IP crime is anything but victimless

—it is a crime that threatens our nation’s well-being, attacking our economy, public welfare, and national

security.

We are fortunate to benefit from an economy that is thriving from brilliant innovations and

breakthroughs in technology and health. Our innovations are also the envy of the world. Unfortunately, as

our developments become more efficient and important, the motivation and means to enable IP crime

continue to grow accordingly. With the spread of innovation comes the threat of increased harms to an

increased number of people by counterfeit products that can cause serious bodily injury or even death.

The criminals who carry out IP offenses increasingly use cyber means to steal more swiftly, effectively,

and with less traceability. We, therefore, have had to become faster, smarter, and better coordinated to

track them down.

The Department has responded to these threats with a strong and coordinated approach. Through

the leadership and coordination of the Attorney General’s IP Task Force, created 2010, the Department

has remained coordinated in confronting the growing number of domestic and international IP crimes.

Through its members, the Task Force works to identify and implement a multi-faceted strategy with our

federal, state, and international partners to effectively combat this type of crime.

We appreciate this opportunity to ensure that the investigators and prosecutors who fight IP crime

on the front lines are acquainted with the tools that are available through the Task Force writ large or

through specific Task Force members.

II. Mission, priorities, and composition

The mission of the Department’s IP Task Force is to support prosecutions in priority areas,

provide heightened civil enforcement, achieve greater coordination among federal, state, and local law

enforcement partners, and increase focus on international enforcement efforts.

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 3

Specifically, the IP Task Force supports the Department’s efforts to aggressively investigate and

prosecute a wide range of IP crimes, with a particular focus on: (1) public health and safety, (2) theft of

trade secrets and economic espionage, and (3) large-scale commercial counterfeiting and piracy. The

Department places a special emphasis on the investigation and prosecution of IP crimes that are

committed or facilitated by cyber-enabled means or perpetrated by organized criminal networks. The IP

Task Force also supports state and local law enforcement’s efforts to address criminal intellectual

property enforcement by providing grants and training.

IP Task Force members include the Assistant Attorney Generals (or equivalent) for the following

components:

• Antitrust Division

• Civil Division

• Criminal Division

• Federal Bureau of Investigation

• National Security Division

• Office of Justice Programs

• Office of Legislative Affairs

• Office of Public Affairs

• United States Attorneys’ offices/Executive Office for United States Attorneys

The IP Task Force also works closely with the Office of the Intellectual Property Enforcement

Coordinator, housed in the White House Office of Management and Budget.

III. Members of the IP Task Force

The Department investigates and prosecutes a wide range of IP crimes. Primary investigative and

prosecutorial responsibility within the Department rests with the FBI, the United States Attorneys’

offices, the Criminal Division’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS), the National

Security Division (NSD), and, with regard to offenses arising under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act,

the Consumer Protection Branch of the Civil Division. Each Task Force member plays an essential role in

the coordinated effort to investigate, prosecute, and prevent IP crimes, as discussed in each brief summary

below.

A. Antitrust Division

The mission of the Antitrust Division is to promote economic competition through enforcing and

providing guidance on antitrust laws and principles. Consumers, and the economy as a whole, benefit

from the competition and innovation that result from consistent application of sound antitrust principles to

intellectual property rights. The Division accomplishes its mission by enforcing the Federal antitrust laws

against illegal, collusive, or exclusionary conduct, while supporting the incentives to innovate created by

intellectual property rights; promoting the procompetitive use of intellectual property rights through

guidelines, appellate briefs, policy statements, reports, hearings, workshops, and speeches; and actively

engaging with our foreign counterparts and multilateral organizations to promote application of

competition laws to intellectual property rights that is based on analysis of competitive effects, not

domestic or industrial policy goals.

4 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

More information about the Antitrust Division is available at http://www.justice.gov/atr.

B. Civil Division

The Civil Division serves a critical role in protecting and enforcing intellectual property rights

and in protecting the public interest in the proper functioning of the intellectual property laws. In the

intellectual property field, as elsewhere, the Division’s principal function is to represent the United States,

federal agencies, and federal officials in civil litigation, both as a party and amicus curiae. In conjunction

with the Office of the Solicitor General, Civil Division plays a leading role in formulating and presenting

the views of the United States on intellectual property matters in response to invitations from the Supreme

Court, the Federal Circuit, and other courts. In addition, Civil Division attorneys participate in outreach

and training programs to promote the protection of intellectual property rights and combat trade in

counterfeit goods. The components of the Civil Division principally involved in intellectual property

matters are the Consumer Protection Branch, the Intellectual Property Section of the Commercial

Litigation Branch, and the Appellate Staff.

The Consumer Protection Branch leads the Justice Department’s efforts to enforce consumer

protection statutes throughout the United States. Its cases are rooted in our nation’s fundamental

consumer protection laws, establishing crucial precedents and protecting American consumers from

threats to their health, safety, and wallet. The Consumer Protection Branch works closely with agencies

such as the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Product Safety

Commission, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau.

The Intellectual Property Section of the Commercial Litigation Branch represents the United

States in matters where a patent, copyright, trademark, or trade secret is at issue. Many of the cases the

Section handles involve complex technologies, such as pharmaceutical compositions and highly

sophisticated electronic devices. In order to meet the challenges presented by these cases, all attorneys

assigned to the Section have a degree in one of the physical sciences or in an engineering field, and are

eligible for admission to practice before the United States Patent and Trademark Office in patent matters.

The Appellate Staff represents the United States, its agencies, and officers in civil cases in the

federal courts of appeals. The Appellate Staff handles appeals involving all of the subject-matter areas

litigated by the Civil Division, including intellectual property matters, and practices in all 13 of the

federal courts of appeals, as well as in the United States Supreme Court. The Appellate Staff's portfolio

includes many of the most difficult and controversial civil cases in which the Federal Government is

involved.

More information about the Civil Division is available at http://www.justice.gov/civil

; the IP

Section of the Commercial Litigation Branch at http://www.justice.gov/civil/intellectual-property-section;

the Consumer Protection Branch at http://www.justice.gov/civil/consumer-protection-branch; and the

Appellate Staff at http://www.justice.gov/civil/appellate-staff.

C. Criminal Division

The Criminal Division’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS) pursues

three overarching goals: to deter and disrupt computer and IP crime, to guide the proper collection of

electronic evidence by investigators and prosecutors, and to provide technical and legal advice and

assistance on these issues to agents and prosecutors in the United States and around the world. CCIPS

accomplishes its mission by pursuing and coordinating investigations and prosecutions, and helping

others to do so; by engaging in activities that build the international legal and operational environment

that allows for successful investigations and prosecutions; by providing expert legal and technical advice

and support to the Department, investigative agencies, and other executive branch agencies; and by

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 5

developing and advocating for policies and legislation relating to computer crime, IP crime, and

collection of electronic evidence. CCIPS’s work often entails close coordination on national security,

intelligence, and international issues.

More information about CCIPS is available at www.cybercrime.gov

.

D. Federal Bureau of Investigation

Preventing intellectual property theft is a priority of the FBI’s criminal investigative program.

The FBI specifically focuses on the theft of IP products that can impact consumers’ health and safety,

such as counterfeit aircraft, car, and electronic parts. Their recent investigative successes are due to

linking the considerable resources and efforts of the private sector with law enforcement partners on local,

state, federal, and international levels.

Given the level of IP protection priority and an interest in maximizing the use of resources, the

FBI has recently announced a new collaborative strategy. This new strategy builds upon the work

previously done by the Department, while also working with industry partners to make enforcement

efforts more effective. As part of this strategy, the FBI will partner with third-party marketplaces to

ensure they have the right analytical tools and techniques to combat intellectual property concerns on

their Web sites. The FBI also will serve as a bridge between brand owners and third-party marketplaces in

an effort to mitigate instances of the manufacture, distribution, advertising, and sale of counterfeit

products. This new strategy will help law enforcement and companies better identify, prioritize, and

disrupt the manufacturing, distribution, advertising, and sale of counterfeit products. High level, more

complex crimes can then be investigated by the FBI and other partner law enforcement agencies of the

National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center. See Department of Justice Press Release,

Justice Department Announces New Strategy to Combat Intellectual Property Crimes and $3.2 Million in

Grant Funding to State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies (Oct. 2, 2015), available at

http://www.

justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-loretta-e-lynch-announces-new-intellectual-property-

enforcement-program.

More information about the FBI’s investigation of intellectual property rights is available

at https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/white_collar/ipr/ipr

. For more information regarding the

National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center, please see the article in this issue entitled “IPR

Center: Conducting Effective IP Enforcement.”

E. National Security Division

The NSD’s mission is to carry out the Department's highest priority: to combat terrorism and

other threats to national security. With respect to intellectual property, NSD’s Counterintelligence and

Export Control Section works with the FBI, DHS, and U.S. Attorney’s offices across the country to

investigate, prosecute, and otherwise disrupt economic espionage and export control offenses.

Additionally, the Office of Intelligence provides legal support to the FBI and other members of the

Intelligence Community in conducting surveillance under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, and,

in particular, investigations involving the theft of intellectual property with national security dimensions.

As a reflection of NSD’s prioritization of national security threats involving malicious cyber activity, in

2012 NSD and CCIPS jointly stood up the National Security Cyber Specialists Network, composed of

prosecutors in every U.S. Attorney’s office and attorneys at Main Justice. This is a resource for training

and coordination on computer hacking offenses with national security implications, many of which

involve the theft of trade secrets and sensitive military technology.

More information about the National Security Division is available at

http://www.justice.

gov/nsd, as well as the article entitled “DOJ’s Strategic Plan for Countering the Economic Espionage

Threat” included in this issue.

6 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

F. United States Attorneys’ offices

The United States Attorneys serve as the nation’s principal litigators under the direction of the

Attorney General. Through the Cyber and Intellectual Property subcommittee of the Attorney General’s

Advisory Committee, designated U.S. Attorneys advise the Attorney General about policies and issues

relating to intellectual property enforcement. The subcommittee is led by its chairperson, U.S. Attorney

David Hickton of the Western District of Pennsylvania, and its vice-chair, U.S. Attorney Rod Rosenstein

of the District of Maryland.

In each United States Attorney’s office, one or more Assistant United States Attorneys (AUSAs)

has received specialized training in the enforcement of intellectual property laws through the Computer

Hacking and Intellectual Property (CHIP) program. CHIP attorneys have four major areas of

responsibility including: (1) prosecuting computer crime and IP offenses, (2) serving as the district’s

legal counsel on matters relating to those offenses and the collection of electronic evidence, (3) training

prosecutors and law enforcement personnel in the region, and (4) conducting public and industry outreach

and awareness activities. These CHIP attorneys and other AUSAs work closely with special agents from

the FBI, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and other federal law enforcement agencies to

investigate and prosecute violations of federal copyright, trademark, and trade secrets laws.

More information about United States Attorney’s offices is available at

http://www.justice

.gov/usao. Please visit http://www.justice.gov/usam/usam-9-50000-chip-guidance for more information

about the CHIP program.

G. Office of Justice Programs

Housed in the Department's Office of Justice Programs, the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA)

provides leadership and assistance to state and local partners, including the Intellectual Property Theft

Enforcement Program (IPEP), in coordination with the Department of Justice’s Computer Crime and

Intellectual Property Section and Task Force on Intellectual Property. The IPEP was initiated at the

direction of the Attorney General in FY 2009, and consists of three major components: law enforcement

efforts at the state and local level, a national training and technical assistance program, and a public

education campaign. Since that time, BJA has awarded over $19 million in funding to support our

partners in their fight against IP crime, including grants and training and technical assistance, over $14

million of which was in awards to local law enforcement agencies.

More information about the Office of Justice Programs is available at http://ojp.gov/

, as well as

the article entitled “Intellectual Property Enforcement Programs: Helping State and Local Law

Enforcement Combat Intellectual Property Crime” included in this issue.

IV. Conclusion

Drawing on the strengths of each of its members and each of its partners in both government and

private industry, the Department’s enforcement efforts against IP crime are more strategic, collaborative,

and impactful than ever before. The Task Force will continue to support the Department’s coordinated

approach to effectively combatting IP crime in the United States and abroad— working to identify and

evolve the Department’s response as criminals continue to advance their schemes.

For more information about the IP Task Force, updates on IP enforcement, and additional

resources, please visit http://www.justice.gov/iptf

.❖

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 7

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Deciding When to Prosecute an

Intellectual Property Case

Christopher S. Merriam

Deputy Chief for Intellectual Property

Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section

U.S. Department of Justice

Kendra R. Ervin

Assistant Deputy Chief for Intellectual Property

Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section

U.S. Department of Justice

I. Introduction

Federal prosecutors know that deciding whether to prosecute a particular case requires the

exercise of judgment and discretion, which can take years of experience and many cases to develop.

Although intellectual property (IP) crimes are not charged as regularly as many other types of federal

offenses, the prosecution of IP cases can have a significant effect in protecting the public and limiting

economic harm to victims, while at the same time creating a substantial deterrent to similar conduct by

others. How should you decide whether a particular case of trafficking in counterfeit computer chips,

copying and distribution of pirated music or software over the Internet, or the theft of trade secrets should

be charged, even where a victim or investigator provides evidence to prove all the elements? What special

considerations may come into play in a given case? Federal prosecutors may need to recalibrate the usual

standards for case consideration when evaluating the merits of an IP case based on a few characteristics of

such cases, including:

• IP crime always has a direct victim (the holder of the IP rights infringed), but it also undermines

the IP system as a whole, may involve fraud perpetrated on the recipient of the counterfeit good

or pirated work, and will often involve related offenses ranging from smuggling and money

laundering to computer intrusions and the distribution of malware.

• Although the majority of IP infringement may be addressed through civil action by the rights

holder, there are many instances where civil remedies are not effective because of the difficulty in

identifying a party through civil process, infringers doing business overseas, or in cases where

repeat infringers ignore or avoid civil judgments.

• Effective enforcement of IP laws is essential to the foundation of the modern economy in both

protecting consumers and encouraging innovation.

❏

Miriam H. Vogel is Associate Deputy Attorney General. In addition to serving as the staff lead on the

Department’s Intellectual Property Task Force, she works with several components on behalf of the

Deputy Attorney General, including Antitrust and the Community Relations Service. Prior to coming to

the Department of Justice, she served as an in-house attorney and in private practice, with a focus on

intellectual property law.

✠

8 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

• The protection of IP rights in cases involving the public health and safety, large scale commercial

piracy and counterfeiting, and the theft of trade secrets are DOJ priority prosecution areas

identified by the Deputy Attorney General through the IP Task Force.

The Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section’s Prosecuting Intellectual Property

Crimes manual serves as a valuable resource for evaluating these, as well as the other issues, that arise in

IP cases. See Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section, Prosecuting

Intellectual Property Crimes (2013). In general, with respect to IP crimes, federal prosecutors should take

into account the same considerations as they would with any federal crime. See, e.g., U.S. Attorneys’

Manual § 9-27.220. While individual U.S. Attorney’s offices may evaluate these factors using different

standards, the discussion below attempts to tailor these factors to issues likely to surface in criminal IP

matters.

II. The federal interest in prosecution of IP crimes

In determining the scope of the federal interest that would be served by a prosecution of a

particular IP case, the attorney for the government needs to weigh several relevant considerations,

including:

(1) [current] Federal law enforcement priorities; (2) The nature and seriousness of the

offense; (3) The deterrent effect of prosecution; (4) The person’s culpability in

connection with the offense; (5) The person’s history with respect to criminal activity; (6)

The person’s willingness to cooperate in the investigation or prosecution of others; and

(7) The probable sentence or other consequences if the person is convicted.

Id. § 9-27.230. This article discusses each of these factors below with detailed attention to IP crimes. The

last factor—the probable sentence—warrants particular attention in light of several amendments over the

past decade to sentencing guideline § 2B5.3 to more accurately reflect the loss caused by IP crime.

A. The federal focus on IP crime

Recognition of the importance of IP to the national economy, and the growing scale of IP theft,

led the Department of Justice to designate IP crime as a “priority” for federal law enforcement as early as

1999. In 2010, Attorney General Holder instituted the current version of the Department’s Intellectual

Property Task Force to emphasize the importance of intellectual property in a wide range of DOJ

responsibilities. The work and priorities of the IP Task Force are spelled out in greater detail in a separate

article in this issue, but it is worth emphasizing the particular focus on the identified prosecution

priorities: (1) Health and Safety of the American Public, (2) Theft of Trade Secrets and Economic

Espionage, and (3) Large-Scale Commercial Counterfeiting and Piracy Operations. To support

investigations and prosecutions in this area, the Department has more than 260 Computer Hacking and

Intellectual Property (CHIP) attorneys across the country who receive special training to address both IP

and cyber-crimes, and 16 attorneys in the Criminal Division’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property

Section specializing entirely on IP crime. Both the FBI and ICE/HSI have agents specifically assigned to

handle IP cases, and a total of 23 domestic and international law enforcement agencies coordinate on IP

cases through the National Intellectual Property Rights Coordination Center, while the Department’s

Bureau of Justice Assistance provides grants and training to support IP investigations and prosecutions by

state and local authorities.

B. The nature and seriousness of the offense

Just as with other criminal offenses, the nature and seriousness of IP crimes varies, and the

consideration of the specific facts and circumstances surrounding each case is critical. Limited federal

resources should not be diverted to prosecute inconsequential cases or cases in which the violation is only

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 9

technical. U.S. Attorneys’ Manual § 9-27.230. Prosecutors may consider any number of factors to

determine the seriousness of an IP crime, including:

1. Whether the counterfeit goods or services endanger the public’s health or safety (e.g.,

counterfeit drugs or automotive parts)

2. The nature of the trade secret information (e.g. critical technologies with military or other

sensitive applications)

3. The scope of the infringing or counterfeiting activities (e.g., whether the subject infringes

or traffics in multiple items or infringes upon multiple industries or victims), as well as

the volume of infringing items manufactured or distributed

4. The scale of the infringing or counterfeiting activities (e.g., the amount of illegitimate

revenue and any identifiable illegitimate profit arising from the infringing or

counterfeiting activities)

5. The number of participants and the involvement of any organized criminal group

6. The scale of the victim’s loss or potential loss, including the value of the infringed item

or trade secret information, the impact of the infringement or trade secret theft on the

market for the infringed item, and the damage to the rights holder’s or trade secret

owner’s business

7. Whether the victim or victims took reasonable measures (if any) to protect against the

crime

8. Whether the purchasers of the infringing items were victims of a fraudulent scheme, or

whether there is a reasonable likelihood of consumer mistake as a result of the subject’s

actions

C. The deterrent effect of prosecution

Deterrence of criminal conduct is one of the primary goals of the criminal justice system.

Experience demonstrates that many infringers will not be deterred by civil liability, which they can treat

as a cost of doing business. For example, even when the rights holder has obtained a permanent injunction

or consent decree, that civil remedy may not necessarily deter some defendants. A defendant may respond

to such civil remedies by altering the item upon which they are infringing, such as counterfeiting

automotive parts bearing marks of one automotive manufacturer after being the subject of an injunction

obtained by another automotive manufacturer. Another defendant may shut down his operations only to

quickly reopen under a different corporate identity.

Criminal prosecution may more effectively deter a violator from repeating his or her crime.

Criminal prosecution of IP crimes is also important for general deterrence. Many individuals may commit

intellectual property crimes not only because they can be relatively easy to commit with technological

advances and more sophisticated methods of manufacturing and distribution, but also because the subjects

believe they will not be prosecuted. Criminal prosecution plays an important role in shaping public

perceptions of right and wrong. The resulting public awareness of effective prosecutions can have a

substantial deterrence effect. Even relatively small scale violations, if permitted to take place openly and

frequently, can lead members of the public to believe that such illicit conduct is tolerated in American

society. While some cases of counterfeiting or piracy may not result in provable direct loss to the rights

holder, the widespread commission of IP crimes with impunity can be devastating to the value of such

rights.

10 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

D. The individual’s culpability in connection with the offense

Multiple individuals working in concert, such as a company that traffics in counterfeit goods or

pirated software, often commit IP crimes. See Prosecuting Intellectual Property Crimes § XI.E (2013)

(discussing special considerations for cases involving corporations). The individuals in such an

organization are not necessarily equally culpable. For example, a prosecutor may reasonably conclude

that some course other than prosecution would be appropriate for a relatively minor participant. In

considering the relative culpability of specific individuals within a larger organization, a number of non-

exclusive factors have proven helpful, including: (1) whether the person had oversight responsibility for

others, (2) whether the person specifically directed others to commit the offense, (3) whether the person

profited from the offense, (4) whether the person was specifically aware of the wrongful nature of the

activity, as evidenced by the receipt of a warning such as a “cease and desist” letter from the rights holder

or a seizure notice letter from Customs and Border Protection (CBP), or by a statement to collaborators

admitting wrongfulness, but nonetheless continued to engage in the activity, and (5) whether the person

took affirmative steps, such as creating misleading records or destroying evidence, to deter investigation,

and thereby facilitate commission of the offense.

E. The individual’s history with respect to criminal activity

The subject’s history with respect to criminal activity will, of course, be extremely fact

dependent. Defendants may have a history of engaging in a pattern of fraudulent conduct not necessarily

limited to IP crimes. It should not be assumed that commission of an IP crime is an exception to an

otherwise law-abiding life. The repeat-offender provisions in the intellectual property crime statutes, e.g.

18 U.S.C. § 2320(b)(1)(B), and the United States Sentencing Guidelines, try to ensure that repeat

offenders receive stiffer sentences.

In addition to the defendant’s criminal history, it is appropriate to consider his or her history of

civil IP violations. Sources for determining the defendant’s history of civil IP offenses include civil

litigation records, the victim’s legal department and private investigators, and any state consumer

protection agencies to which consumers might have complained.

F. The individual’s willingness to cooperate in the investigation or prosecution of others

A defendant’s willingness to cooperate will depend on the individual. Nevertheless, it is

important to recognize that in IP cases, defendants often have a substantial capacity for cooperation, if

they are, in fact, willing. Since IP crimes often require special materials, equipment, or information, and

can involve multiple participants across the supply chain, defendants often can provide substantial

assistance. A defendant might provide valuable information concerning a domestic or foreign source of

counterfeit goods or pirated works. For instance, if a defendant is investigated for selling counterfeit

health care products on a retail basis, he could provide information as to the wholesaler of those

counterfeit products. The wholesaler, in turn, could provide information regarding the manufacturer, or

about other retailers.

G. The probable sentence or other consequences upon conviction

The consequences that may be imposed if an IP prosecution is successful include imprisonment,

restitution, and forfeiture. In Prosecuting Intellectual Property Crimes, the sentencing provisions are

discussed at § VIII.B-C, whereas restitution (which is generally mandatory in IP cases) is discussed at

§ VIII.D, and forfeiture (which is generally available in IP cases) is discussed at § VIII.E. The probable

sentence is worthy of attention in light of revisions over the past decade to sentencing guidelines § 2B1.1

for Economic Espionage Act (EEA) cases and § 2B5.3 for all other IP offenses.

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 11

Completed EEA cases are sentenced under § 2B1.1, with a base offense level of 6. The value of

the stolen trade secret information largely drives the defendant’s sentence as the offense level increases

according to the amount of loss under § 2B1.1(b)(1). Section 2B1.1, Application Notes, outlines a number

of general methods for calculating loss, and the Prosecuting Intellectual Property Crimes Manual

§ VIII.C.2 provides further explanation regarding factors to consider for loss calculations in trade secret

cases, as well as case law describing potential ways to value trade secrets.

Additionally, as of November 1, 2013, the offense level is increased two points if the defendant

knew or intended that the trade secret would be transported or transmitted out of the United States, see

U.S.S.G. § 2B1.1(b)(12)(A) (2015), and four points if the defendant knew or intended that the offense

would benefit a foreign government, foreign instrumentality, or foreign agent, with a minimum offense

level of 14. See id. § 2B1.1(b)(12)(B). Other enhancements that often arise in EEA cases include the two-

level “sophisticated means” enhancement under § 2B1.1(b)(10(C) and the two-level adjustment for abuse

of a position of trust or use of a special skill under § 3B1.3.

For all other IP offenses, § 2B5.3 governs the sentencing calculations. Since 2000, there have

been five rounds of amendments to this guideline. Several of these amendments are highlighted below,

and the Prosecuting Intellectual Property Crimes Manual § VIII.C.1 discusses each in more detail, and

provides an overview of the guideline calculations for IP offenses governed by § 2B5.3, including

commonly sought enhancement and departure considerations.

• In 2000, the base offense level was increased from 6 to 8, and, in addition to the infringement

amount, the number and type of special offense characteristics were increased to include

characteristics for manufacturing, uploading, or importing infringing items; for infringement not

committed for commercial advantage or private financial gain; and for risk of serious bodily

injury or possession of a dangerous weapon in connection with the offense. See U.S.S.G. App. C

(Amendments 590, 593).

• In 2005 on a temporary basis, and in 2006 as permanent, a new specific offense characteristic

addressing infringement of pre-release works was added. See U.S.S.G. App. C (Amendments

675, 687).

• In 2006 on a temporary basis, and in 2007 as permanent, § 2B5.3 was amended to specify that in

cases under 18 U.S.C. § 2318 or § 2320 involving counterfeit labels, the infringement amount is

based on the retail value of the infringed items to which the labels would have been affixed. See

U.S.S.G. App. C (Amendments 682, 704).

• Most recently, as of the November 1, 2013, if the offense involved a counterfeit drug or

counterfeit military goods and services under certain conditions, the offense level is increased by

2. See U.S.S.G. App. C (Amendment 773). The amendment also specified a minimum offense

level of 14 for offenses involving counterfeit military goods and services. See id.

III. Whether the person is subject to prosecution in another jurisdiction

The U.S. Attorneys’ Manual § 9-27.220 also notes that a prosecutor may properly decline to take

action despite having sufficient admissible evidence when the person is subject to effective prosecution in

another jurisdiction. In IP cases, as in other cases, “[a]lthough there may be instances in which a Federal

prosecutor may wish to consider deferring to prosecution in another Federal district, in most instances the

choice will probably be between Federal prosecution and prosecution by state or local authorities.” U.S.

Attorneys’ Manual § 9-27.240 (cmt). To make this determination, prosecutors should weigh all relevant

considerations, including: (1) the strength of the other jurisdiction’s interest in prosecution, (2) [t]he

other jurisdiction’s ability and willingness to prosecute effectively, and (3) [t]he probable sentence or

other consequences if the person is convicted in the other jurisdiction. Id. § 9-27.240.

12 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

Unlike in many other types of criminal offenses, a prosecutor in an IP case arguably may not be

able to defer to a prosecution in the location of the primary victim. For example, a multinational

corporation headquartered in one state may be the victim of trade secret theft without any nexus between

the misappropriation and the district in which the victim company is based. Because of the defendant’s

constitutional and statutory right to be tried in the state and district in which the crime was “committed,”

U.S. Const. art. III § 2 cl. 3; U.S. Const. amend. 6; 18 U.S.C. § 3237, a prosecutor based in the home state

of the victim arguably may not have proper venue over the defendant unless he or she can show that the

“locus delecti” of the counterfeiting took place in that district. This determination must be made “from the

nature of the crime alleged and the location of the act or acts constituting it.” United States v. Rodriguez-

Moreno, 526 U.S. 275, 280 (1999).

Thus, in IP cases, a federal prosecutor often will be called upon to vindicate the rights of

a victim IP holder based in another district, another state, or even another country, because the

defendant may not be subject to prosecution in the victim’s district, state, or nation. Federal

prosecutors should also recognize that local or state authorities may not have a great interest in

punishing violations of the rights of out-of-state victim IP holders. By contrast, ensuring uniform

and reliable national enforcement of the IP laws is an important goal of federal law enforcement.

This goal takes on added significance for federal prosecutors when the victim is based in

a foreign country because of the importance of IP in modern international trade. With consistent

enforcement of IP rights, the United States will continue to set an example of vigorous IP rights

enforcement and to be perceived as hospitable to foreign firms that would register their IP and

engage in business here.

Local and state authorities may also believe that since many IP rights are conferred by the

federal government, they do not have the ability to prosecute any IP crimes. Federal IP laws,

however, generally do not preempt state and local IP laws. There is a provision for federal

preemption for copyright infringement, 17 U.S.C. § 301, although this preemption permits

prosecution for other kinds of crime, and some states have passed laws that indirectly criminalize

conduct involving certain pirated works. Moreover, even if the local or state authorities express a

strong interest in prosecution, they may not have the ability or willingness to prosecute the case

effectively due to competing priorities and limited resources. Consequently, a prosecutor should

evaluate for each individual case whether state or local law enforcement exists as a viable

alternative to federal prosecution.

IV. The adequacy of a noncriminal alternative in an IP case

Prosecutors may consider the adequacy of noncriminal alternatives when addressing an IP case.

Some civil remedies, including ex parte seizure of a defendant’s infringing products and punitive

damages, may be available for certain violations of copyright and trademark rights. 15 U.S.C. § 1116(d)

(2015) (trademark remedies); 17 U.S.C. §§ 502-505 (2015) (copyright remedies). Also, for importers of

trademark-infringing merchandise, CBP may assess civil penalties not greater than the value that the

merchandise would have were it genuine, according to the manufacturer’s suggested retail price for first

offenders, and not greater than twice that value for repeat offenders. These civil fines may be imposed in

CBP’s discretion, in addition to any other civil or criminal penalty or other remedy authorized by law. 19

U.S.C. § 1526(f) (2015). The availability and adequacy of these remedies should be carefully considered

when evaluating an IP case.

Yet civil remedies may be futile under some circumstances. For example, IP crimes are unusual

because they often are committed without the victim company’s knowledge. The victim usually has no

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 13

direct relationship with the infringer—before, during, or after the commission of the crime. If a victim

remains unaware of a violation by a particular defendant, civil remedies generally will be unavailing.

Furthermore, without criminal sanction, infringers or counterfeiters might treat the rare case of the

victim’s civil enforcement of its rights as a cost of doing business.

Another important factor to consider when contemplating civil remedies is that infringers may be

judgment proof. In most cases, the infringer traffics in counterfeit items worth far less than the authentic

ones, and with the increasing prevalence of online sales of counterfeit and pirated goods, the infringer

only needs limited resources to operate his or her business.

There are a number of other circumstances where existing civil remedies may simply be an

insufficient deterrent. For example, there may be cases where there have been prior unsuccessful efforts

by a victim to enforce IP rights against the defendant or the existence of circumstances preventing such

efforts. Criminal charges may be necessary if counterfeiting, piracy, or theft of trade secrets continues

despite the entry of a permanent injunction or consent decree in a civil case.

V. Conclusion

Because defendants in IP cases can have several victims, including the IP holders or trade secret

owners, society at large, and the recipients of the infringing goods or works, and because reliable

enforcement of federally created IP rights is so important to the growing information economy, federal

prosecutors should carefully consider opportunities to prosecute IP cases. Prosecutors should be aware of

the special characteristics of IP cases when evaluating them against traditional principles and exercising

their prosecutorial discretion. Further guidance is available from the Prosecuting Intellectual Property

Crimes Manual (2013), or from the IP Team at the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section

(CCIPS) at (202) 514-1026.❖

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

❏

Christopher S. Merriam is the Deputy Chief for Intellectual Property with the Computer Crime and

Intellectual Property Section of the U.S. Department of Justice. Mr. Merriam leads a group of 15 attorneys

dedicated to intellectual property prosecutions and related issues. During his time at CCIPS, Mr. Merriam

has prosecuted cases of copyright and trade secret theft, and acted as the national contact for trade secret

theft cases arising under the Economic Espionage Act of 1996. He has also worked directly with law

enforcement colleagues in more than 20 nations to help improve criminal enforcement of intellectual

property laws.

Before joining the Justice Department in 2001, Mr. Merriam was a criminal defense lawyer with the firm of

Rochon & Roberts in Washington, DC. Mr. Merriam was an E. Barrett Prettyman Fellow at the Georgetown

University Law Center Criminal Justice Clinic, where he taught criminal law and practice.✠

❏Kendra R. Ervin is the Assistant Deputy Chief for Intellectual Property with the Computer Crime and

Intellectual Property Section of the U.S. Department of Justice. Ms. Ervin assists Deputy Chief Christopher

Merriam in leading a group of 15 attorneys dedicated to IP prosecutions and related issues. In her five years

with CCIPS, Ms. Ervin has prosecuted large-scale, multi-jurisdictional IP crimes, participated in domestic

and international IP enforcement training and outreach, and helped to develop and draft legislative and

policy initiatives addressing all facets of IP crime.

Prior to joining CCIPS, Ms. Ervin was employed as an associate at the law firm of Williams & Connolly,

where she specialized in patent litigation. Ms. Ervin also served as a law clerk on the United States Court of

Appeals for the Federal Circuit.✠

14 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

This article updates an earlier article written by David Goldstone for the March 2001 issue of the United

States Attorneys’ Bulletin.

Loss Amount in Trade Secret Cases

William P. Campos

Assistant United States Attorney

Intellectual Property Crimes Coordinator

Eastern District of New York

I. Introduction

Intellectual property plays an important role in the United States economy. President Obama

noted that “[o]ur single greatest asset is the innovation and the ingenuity and creativity of the American

people. It is essential to our prosperity and it will only become more so in this century.” See

http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-exportimport-banks-annual-conference .

Likewise, President Clinton noted that “[t]rade secrets are an integral part of virtually every sector of our

economy and are essential to maintaining the health and competitiveness of critical industries operating in

the United States. Economic espionage and trade secret theft threaten our Nation’s national security and

economic well-being.” See Presidential Statement on Signing the Economic Espionage Act of 1996, 2

Pub. Papers 1814-15, 1996 WL 584924 (Oct. 11, 1996).

Economic espionage is a significant threat to American businesses, particularly as the United

States moves to a high-technology economy. The theft of sensitive business information is not only

damaging to businesses, but is also difficult to detect when done by company insiders.

Congress responded to the adverse impact that trade secret theft has on the U.S. economy in

enacting the Economic Espionage Act of 1996 (EEA): “The development and production of proprietary

economic information is an integral part of U.S. business and is thus essential to preserving the

competitiveness of the U.S. economy.” S. Hrg. 104-499, at 2, 1996 WL 90824 (Feb. 28, 1996) (opening

statement of Sen. Arlen Specter). “A piece of information can be as valuable to a business as in fact a

factory is. The theft of that information could do more harm than if an arsonist torched that factory.” Id. at

3, 1996 WL 90789 (Feb. 28, 1996) (opening statement of Sen. Herb Kohl).

In considering whether to enact the EEA, Congress found that “[o]nly by adopting a national

scheme to protect U.S. proprietary economic information can we hope to maintain our industrial and

economic edge and thus safeguard our national security.” S. Rep. 104-359, 11-12, 1996 WL 497065 (July

30, 1996); see also H.R. Rep. 104-788, reprinted in 1996 U.S.C.C.A.N. 4021, 4025 (Sept. 16, 1996)

(finding that a “comprehensive federal criminal statute” “will serve as a powerful deterrent to this type of

crime” and would “better facilitate the investigation and prosecution of [trade secret theft]”).

II. The Guidelines

The EEA, codified at Title 18, United States Code sections 1831 to 1839, provides for the

criminal prosecution of trade secret theft and misappropriation. An important factor in determining a

criminal defendant’s appropriate sentencing range under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines (U.S.S.G. and

the Guidelines) is the calculation of the “loss amount” pursuant to Section 2B1.1 of the Guidelines. This

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 15

article is intended to address the methods that have been, or could be, used in calculating the loss amount

in trade secret cases.

Generally, the applicable loss amount to be applied to the §2B1.1 table is the greater of the actual

or intended loss to the victim. See U.S.S.G. § 2B1.1, app. n.3(A) (2015). Under the Guidelines, actual loss

is measured as “the reasonably foreseeable pecuniary harm that resulted from the offense,” and intended

loss is measured as the “pecuniary harm that was intended to result from the offense and includes

intended pecuniary harm that would have been impossible or unlikely to occur (e.g., as in a government

sting operation, or an insurance fraud in which the claim exceeded the insured value).” Id. cmt. n.3(A)(i-

ii). The Guidelines also provide a non-exhaustive list of factors that can be used to estimate the loss

amount. See Id. cmt. n.3(A)(i-ii); United States v. Ferguson, 584 F. Supp. 2d 447, 451 (D. Conn. 2008)

(describing the §2B1.1 cmt. 3(C) factors as “a non-exhaustive list of factors a court might consider in

estimating the loss.”).

For example, if property is taken, copied, or destroyed, the measure of loss may be the fair market

value of the property, or the court may consider using the cost to the victim of replacing that property if

the fair market value is impracticable to determine or inadequately measures the harm. See U.S.S.G.

§ 2B1.1, cmt. n.3(C)(i) (2015). But, regardless of which method is chosen to calculate loss, the

Government’s calculation need not be absolutely certain or precise. “The court need only make a

reasonable estimate of the loss.” See id. § 2B1.1 cmt. n. 3(C).

Many thefts of trade secrets cases, however, involve no loss of tangible property or even actual

loss, depending on how quickly the offender was apprehended by law enforcement agents. In November

2009, therefore, the Guidelines were amended to include Application Note 3(C)(ii), which sets forth that

“[i]n the case of proprietary information (e.g., trade secrets), the cost of developing that information or the

reduction in the value of that information that resulted from the offense” is to be considered in estimating

the loss amount. The amendment made explicit what several courts had already done, namely, to consider

the research and development costs as an alternative measure of the loss amount in a trade secret case. See

e.g. United States v. Ameri, 412 F.3d 893, 900 (8th Cir. 2005); See also United States v. Four Pillars

Enterprise Company, 253 F. App’x 502, 512 (6th Cir. 2007) (unpublished opinion); United States v.

Wilson, 900 F.2d 1350, 1355-56 (9th Cir. 1990). The legislative history of the EEA also touches on the

significance of the research and development costs associated with trade secrets:

As this Nation moves into the high-technology, information age, the value of these

intangible assets will only continue to grow. . . . This material is a prime target for theft

precisely because it costs so much to develop independently, because it is so valuable.

S. Rep. No. 359, 104th Cong., 2d Sess. (1996).

In trade secret cases, however, there is oftentimes no actual market for the information that was

stolen—it had been kept secret. In those cases, as stated in U.S.S.G 3. § 2B1.1, cmt. n.(C)(ii), the loss

amount may be the cost of developing the stolen information or the reduction in value of that information

that resulted from the offense. Regardless of which method is chosen to calculate loss, the Government’s

calculation need only be a “reasonable estimate of the loss,” as required by § 2B1.1 cmt. n.3(C).

III. Preparing for sentencing

In preparing to determine the appropriate loss amount in a trade secret theft sentencing, there first

must be a determination as to whether a loss amount can be reasonably calculated. Among the factors to

consider is whether the defendant was paid for the item or information stolen. The amount paid may be an

appropriate measure of the market value of the trade secret and, hence, the loss amount. If the defendant

did not actually sell the information before the arrest, then one should determine whether he tried to sell

it. Again, the amount of the proposed sale may be an appropriate measure of the market price, and the loss

16 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

amount. In any event, the item or information stolen may have taken years to develop, and one should

also try to determine the research and development costs incurred by the victim. While the research and

development costs may not be the best or sole component of the estimate of Guidelines loss, it may be the

easiest to obtain and explain.

Explaining the Guidelines loss to the court could be challenging. Oftentimes the defendant is

unable to sell the information or otherwise cause his plan to reach fruition. In those cases, the defendant

will argue that the loss amount is zero. The victims of the theft correctly point out that the stolen

information could have caused a catastrophic loss to the company. Given these competing views, which

often amounts to a binary decision matrix (i.e., the loss is zero or 100 percent), it is important to consider

the individual court’s views and to maintain one’s credibility with the court. Consequently, to the extent

possible, one should provide the court with multiple loss calculation methodologies, which likely result in

different loss amounts. If the court has a range of options, it is less likely to assign a value of zero simply

because it rejects one of them.

IV. Examples of loss amount calculations

A good example of providing a court with several loss calculation methodologies is United States

v. Sergey Aleynikov, No. 10 CR 96, 2011 WL 1002237 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 11, 2011). Aleynikov, a former

computer programmer at Goldman Sachs & Co., was convicted of trade secret theft and Interstate

Transportation of Stolen Property, for stealing Goldman Sachs’s proprietary computer code to benefit his

new employer. The Government first argued that the stolen computer code had a fair market value despite

not being for sale or available to the public, in much the same way a house has a fair market value despite

the owner’s refusal to sell it. Other commercially available computer programs performed tasks similar to

those performed by the stolen programs and could serve as a useful measure of the loss. After all, the theft

provided the defendant with a free version of software he would otherwise have had to pay millions to

purchase from third parties. Next, the Government argued that, assuming a fair market value was

impracticable to determine, the cost to the victim of replacing the code should be used. Finally, the

Government argued that the cost of developing the code, as contemplated in §2B1.1 cmt. 3(C)(ii), should

be used, which would be at least in the range of $7 million to $20 million. This was accepted by the court.

The Government provided thoughtful methodologies to support each of the suggested sentencing options.

It should be noted, however, that this case was later reversed by the Second Circuit on grounds of

statutory construction. See 676 F.3d 71 (2d Cir. 2012).

Likewise, in United States v. Samarth Agrawal,

726 F.3d 235 (2d. Cir. 2013), the Government

provided alternate loss methodologies to the court. Agrawal, a former trader at Societe Generale, was

convicted of trade secret theft and Interstate Transportation of Stolen Property. The jury found that he

stole proprietary computer code used for the firm’s high frequency securities trading business. Agrawal

printed the code onto thousands of sheets of paper, which he then physically removed from the bank's

New York office to his New Jersey home. There, he could use them to replicate Societe Generale's

trading systems for a competitor who promised to pay him hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Testimony at Agrawal’s trial suggested that the company benefiting from the theft expected that

the stolen strategy would help the company realize a profit of between $10 million and $40 million.

Indeed, Societe Generale had generated profits of $10 million per year for three years using the

proprietary code. At sentencing, the defendant argued there was no actual loss and no intended loss. The

Government agreed that there had been no actual loss. Ultimately, however, the Government’s successful

argument for a loss amount of between $7 million and $20 million was based, in part, on the fact that the

cost in developing the stolen programs was approximately $9.9 million. Agrawal was sentenced to 36

months’ incarceration.

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 17

In United States v. Hanjuan Jin, 833 F.Supp.2d 977 (N.D. Ill. 2012), affirmed, 733F.3d 718 (7th

Cir. 2013), the defendant was charged with

economic espionage and theft of trade secrets pursuant to 18

U.S.C. §§1831 and 1832, respectively. The defendant, a software engineer at Motorola, stole the iDen

proprietary telecommunications technology. She planned to leave the United States and work in China. A

November 2011 bench trial resulted in her conviction of theft of trade secrets, but acquittal of economic

espionage. The judge imposed a 48-month prison sentence. Both her conviction and 48-month sentence

were affirmed.

At sentencing, the Government explained that Motorola’s 2011 iDen-related revenues were $365

million. The Government also provided the sentencing judge a loss amount calculation based on the

research and development costs associated with some of the stolen information. Based on the research and

development costs of between $20 million and $50 million, the Guidelines range was 121-151 months.

Ultimately, despite the high Guidelines range, the court sentenced the defendant to 48 months’

incarceration because of her significant health issues.

In United States v. Walter Liew, 11 CR 573 (N.D.CA Dec. 9, 2013) (unpublished opinion), Liew

and his co-conspirators were convicted by a jury of economic espionage, among other crimes. Liew stole

trade secrets from the DuPont Company, consisting of the processes to manufacture titanium dioxide

(TiO2), and sold them to a Chinese company. Liew obtained $28 million from the Chinese company.

At sentencing, the Government noted the difficulty in accurately determining loss where the

stolen information represented “decades of research and design at DuPont.” Govt. Sentencing Memo at 6.

Indeed, one DuPont employee who testified at trial stated that, during his tenure at the company,

approximately $150 million was spent annually to improve the TiO2 facilities. See Id. at 7. The

Government rested on the certainty of the $28 million that Liew obtained.

The court sentenced Liew on the Trade secret counts to 120 months’ imprisonment. His 180

month sentence also included his convictions on a witness tampering charge and false statements charges

relating to a bankruptcy proceeding and income tax returns.

V. Conclusion

The Economic Espionage Act is intended to protect innovation and creativity, which is essential

to our economic well-being and our national security. Trade secret theft prosecutions, therefore, are a

significant tool for ensuring that protection. The high-flying rhetoric of the EEA, however, can meet an

unsightly demise without a defensible nuts-and-bolts calculation of an appropriate loss amount, which is

the single most important feature in determining the defendant’s sentencing guidelines.❖

❏

William P. Campos is an Assistant United States Attorney in the Eastern District of New York,

where he serves as the Coordinator for Intellectual Property Crimes. Before joining the United States

Attorneys’ Office, Eastern District of New York, in June 2007, Mr. Campos was an Assistant District

Attorney with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, as well as a litigation associate at Sedgwick

LLP.

✠

18 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

Prosecuting Copyright Infringement

Cases and Emerging Issues

Jason Gull

Senior Counsel

Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section

U.S. Department of Justice

Tim Flowers

Trial Attorney

Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section

U.S. Department of Justice

I. Introduction

Over the past century, various new technologies have emerged that have posed significant

challenges to copyright enforcement. From the player piano to radio, the photocopier to the cassette tape,

new technologies for using, copying, and disseminating creative works have provided great opportunities

for copyright owners and their audiences, but also have often strained existing copyright laws, in many

cases undermining the ability of authors to realize the benefits of copyright in their works. These

disruptive technologies have frequently led to legal changes designed to preserve copyright law’s

incentive structure and ensure that copyrights can be effectively enforced. Perhaps no technology has

expanded opportunities for creating and distributing creative works more than the Internet. Certainly none

has posed more significant challenges to copyright enforcement. From pirate FTP sites that offer free

downloads of software, to peer-to-peer file sharing, new Internet phenomena have often left copyright

law, and law enforcement, struggling to keep pace.

Ten to fifteen years ago—that is, in the ancient past by Internet standards—movies, music, and

other media content available on the Internet was usually distributed in the form of files that could be

downloaded. Although smaller, embedded video and audio files were certainly not unheard of, in general,

for larger media files like complete movies or songs, users needed to download an entire file (and even

wait until the download was complete) before a media file could be listened to or watched. For a large

movie file being downloaded on a typical home Internet connection in the early 2000s, this could take not

just hours, but several days. However, once downloaded, a permanent copy of the media file resides on

the user’s computer, and generally can be replayed or further distributed to others (although some

distributors of Internet media content have employed digital rights management systems that can limit

playback to specific devices, time periods, etc.).

II. Streaming

Internet streaming is a prime example of the type of Internet technology that is both incredibly

useful and, at the same time, poses significant challenges to effective criminal enforcement. Streaming

services offer movies, music, and other media content to users in real time, allowing them to click a

button on a browser window or mobile device app and start watching or listening to movies or music

almost immediately. Unlike downloading a digital media file, streaming does not require a user to wait

until an entire file download is complete before content can be seen or heard. For users, streaming can

offer greater flexibility; instead of having to download and store a complete library of works, users can

January 2016 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 19

stream media from the “cloud” to multiple devices and locations wherever they have an Internet

connection. For media providers, streaming offers the potential benefit of greater control over media files

and a more persistent connection with users, providing more opportunities for advertising.

The growth of streaming media use has been staggering. YouTube, perhaps the best-known

streaming video site today, was founded only a decade ago. Netflix’s streaming video service is even

younger and, on an average evening, Netflix alone now accounts for more than a third of total Internet

traffic in the United States. According to broadband networking firm, Sandvine, in autumn 2015, Netflix

accounted for 36.5 percent of North American downstream Internet traffic during peak evening hours.

Sandvine Global Internet Phenomena Report, Dec. 2015, available

at https://www.sandvine.com/trends/global-internet-phenomena/

. Altogether, streaming services like

Netflix and YouTube, along with many other smaller players like Hulu, HBO Go, Pandora, and Spotify,

now account for more than two thirds of total North American Internet traffic during peak times, up from

about one third of traffic just five years ago.

In the past decade, as high-speed broadband Internet service has become increasingly common,

copyright pirates have gotten into the streaming game, too, with illicit sites offering access to streams of

thousands of movies, television shows, and music files, often for free. MegaVideo, NinjaVideo, and

TVShack are some of the better known sites involved in streaming against which the Department of

Justice has taken action in recent years, but many pirate streaming sites continue to operate, and new ones

are being created all the time.

Compared to the old “download” model, streaming is resource-intensive, requiring not only

significant storage space for media files, but also massive amounts of bandwidth to ensure that media can

be streamed to many users simultaneously, without latency or delays that result in poor video or sound

quality and a bad user experience. Streaming sites can be expensive to run, so many are supported by

subscription fees or “donations.” However, streaming offers the same advantages to copyright pirates that

it does to legitimate media sites, including a persistent connection with users as they watch or listen to

media files. This allows streaming site operators to insert their own advertising, either during pauses in

video or audio content or displayed around a video frame on screen. According to the 2012 indictment

against the operators of Megaupload, that organization and its associated streaming sites brought in more

than $25 million in advertising revenue. See United States v. Kim Dotcom et al., No. 1:12CR3 (E.D. Va.,

filed Jan. 5, 2012), at paragraph 18.

Many illicit streaming sites are also engaged in a more insidious form of “advertising”—the

delivery of malware to users’ devices. According to research commissioned by the Digital Citizens

Alliance, nearly a third of the illicit streaming sites researchers examined exposed visitors to some form

of malware, ranging from invasive adware to remote-access Trojans, and operators of pirate streaming

sites can earn significant amounts of revenue from malware networks that will pay sites operators for

every site visitor they can infect. Digital Bait: How Content Theft Sites and Malware are Exploited by

Cybercriminals to Hack into Internet Users’ Computers and Personal Data, Digital Citizens Alliance,

(Dec. 2015) available at

http://www.digitalcitizensalliance.org/cac/ alliance/ content. aspx?

page=digitalbait.

If the growth in legitimate streaming services is impressive, the growth in illicit streaming sites

serving up pirated content is alarming. Between 2010 and 2012, the amount of bandwidth devoted to

infringing video streaming was estimated to have grown by more than 470 percent, or more than two and

a half times the growth in legitimate streaming over the same period. David Price, Sizing the Piracy

Universe, NetNames, (Sept. 2013) available at

http://www.netnames.com//sites/default/files/netnames-

sizing_piracy_universe-FULLreport-sept2013.pdf. And that growth occurred despite the Department’s

takedown of the widely-used streaming provider, MegaVideo, and its associated site, Megaupload.com.

There is reason to believe that infringing streaming has continued to increase in bandwidth and frequency

since then.

20 United States Attorneys’ Bulletin January 2016

III. Criminal copyright enforcement

Over the past 25 years, criminal copyright enforcement online has concentrated mainly on sites

engaged in making and distributing pirated copies of works, whether those works consist of computer

software, videogames, movies, music, or books. But illicit streaming services challenge law

enforcement’s ability to pursue infringement criminally. The Copyright Act grants the authors of creative

works a set of exclusive rights, including the rights to reproduce copies of the work, to distribute copies

of the work to the public, to prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted work, and (with respect to

certain classes of works) to perform or display the work publically. The list of exclusive rights protected

by copyright are enumerated in 17 U.S.C. § 106. Criminal law currently provides felony penalties for

willful infringements of only two of these rights: an infringement involving violation of either the

reproduction or distribution rights can be punished as a felony, so long as the infringement is above a

certain threshold level (a total of 10 or more copies, with a total retail value of $2500, within a specific

180-day period), or involves online distribution of a work being prepared for commercial distribution

(such as a movie that has not yet been released publicly in theaters).

Streaming does not fit neatly within the “reproduction” or “distribution” framework. Streamed

content is transmitted and watched or listened to more or less in real time, as the content is being

streamed. Generally speaking, streaming does not leave the user with a copy of content that can be

replayed or redistributed later. The nature of digital audio and video is such that any time an audio or

video file is “played,” the file must be copied bit-by-bit from one part of a device to another, stored

temporarily in a buffer, or sent from one device to another. It is not well-settled whether this type of

copying and sending necessarily constitutes “reproduction” or “distribution” of the copyrighted work for

purposes of copyright law. For further discussion of the copyright interests implicated by streaming, see,

Promoting Investment and Protecting Commerce Online: The ART Act, the NET Act and Illegal

Streaming, Statement of Maria A. Pallante, Register of Copyrights, before the House Judiciary

Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, Competition, and the Internet, 112th Congress, 1st Session, (June