JOIN POJC M

Inellecual

Proper and he

U.S. conom:

016 Updae

conomics Saisics

dminisraion

Justin Antonipillai

Counselor to the Secretary

Delegated Duties of the Under Secretary

for Economic Aairs

Robert Rubinovitz, Deputy Chief Economist

David Langdon, Economist and Policy Advisor

Fenwick Yu, Economist

William Hawk, Economist

U.S. Paen and

rademar Oce

Michelle K. Lee

Under Secretary of Commerce for

Intellectual Property and Director,

U.S. Patent and Trademark Oce

Alan C. Marco, Chief Economist

Andrew A. Toole, Deputy Chief Economist

Asrat Tesfayesus, Economist

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae i

CNODMNS

e Project Team would like to thank Vikrum Aiyer, Alexander Beck, David Carson, Amy Cotton,

Edward Elliot, Jim Hirabayashi, Amanda Myers, Nicholas Pairolero, Sandy Phetsaenngam, Shi-

ra Perlmutter, Bridget Petruczok, Roy Rabindranath, Patrick Ross, and Daina Spencer from the

USPTO; Nikolas Zolas and Cynthia Davis Hollingsworth from the Census Bureau; omas How-

ells, Gabriel Medeiros, and Amanda Lyndaker from the Bureau of Economic Analysis; and Ryan

Noonan and Rodolfo Telles from the Economics and Statistics Administration’s Oce of the Chief

Economist for their valuable contributions to this report.

ecuie Summar

Innovation and creative endeavors are indispensable elements that drive economic growth and

sustain the competitive edge of the U.S. economy. e last century recorded unprecedented

improvements in the health, economic well-being, and overall quality of life for the entire U.S.

population.

1

As the world leader in innovation, U.S. companies have relied on intellectual prop-

erty (IP) as one of the leading tools with which such advances were promoted and realized. Pat-

ents, trademarks, and copyrights are the principal means for establishing ownership rights to the

creations, inventions, and brands that can be used to generate tangible economic benets to their

owner.

In 2012, the Department of Commerce issued a report titled Intellectual Property and the U.S.

Economy: Industries in Focus (hereaer, the 2012 report). e report identied the industries

that rely most heavily on patents, trademarks, or copyrights as IP-intensive and estimated their

contribution to the U.S. economy. It generated considerable interest and energized other agencies

and organizations to produce similar studies investigating the use and impact of IP across coun-

tries, industries, and rms.

is report builds on the 2012 version by providing an update on the impact of IP on our econo-

my and a fresh look at the approach used to measure those results. e update continues to focus

on measuring the intensity of IP use, and its persistent relationship to economic indicators such

as employment, wages, and value added. While our methodology does not permit us to attribute

those dierences to IP alone, the results provide a useful benchmark. Furthermore, this and other

studies together make clear that IP is a major part of a robust and growing economy.

Accordingly, in an eort to provide a more comprehensive analysis, this report also incorporates

ndings from other studies that target similar research questions but apply dierent methodol-

ogies. Overall, we nd that IP-intensive industries continue to be an important and integral part

of the U.S. economy and account for more jobs and a larger share of U.S. gross domestic product

(GDP) in 2014 compared to what we observed for 2010, the latest gure available for the 2012

report. We discuss these and other results in more detail below.

1 Gordon 2016.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae ii

Principal indings

• IP-intensive industries continue to be a major, integral and growing part of the

U.S. economy.

• is report identies 81 industries (from among 313 total) as IP-intensive. ese IP-inten-

sive industries directly accounted for 27.9 million jobs in 2014, up 0.8 million from 2010.

• Trademark-intensive industries are the largest in number and contribute the most employ-

ment with 23.7 million jobs in 2014 (up from 22.6 million in 2010). Copyright-intensive

industries supplied 5.6 million jobs (compared to 5.1 million in 2010) followed by pat-

ent-intensive industries with 3.9 million jobs (3.8 million in 2010).

• While jobs in IP-intensive industries increased between 2010 and 2014, non-IP-intensive

jobs grew at a slightly faster pace. Consequently, the proportion of total employment in

IP-intensive industries declined slightly to 18.2 percent (from 18.8 percent in 2010).

• In contrast, the value added by IP-intensive industries increased substantially in both total

amount and GDP share between 2010 and 2014. IP-intensive industries accounted for

$6.6 trillion in value added in 2014, up more than $1.5 trillion (30 percent) from $5.06

trillion in 2010. Accordingly, the share of total U.S. GDP attributable to IP-intensive in-

dustries increased from 34.8 percent in 2010 to 38.2 percent in 2014.

• While IP-intensive industries directly accounted for 27.9 million jobs either on their pay-

rolls or under contract in 2014, they also indirectly supported 17.6 million more supply

chain jobs throughout the economy. In total, IP-intensive industries directly and indirectly

supported 45.5 million jobs, about 30 percent of all employment.

• Private wage and salary workers in IP-intensive industries continue to earn signicantly

more than those in non-IP-intensive industries. In 2014, workers in IP-intensive indus-

tries earned an average weekly wage of $1,312, 46 percent higher than the $896 average

weekly wages in non-IP-intensive industries in the private sector. is wage premium has

largely grown over time from 22 percent in 1990 to 42 percent in 2010 and 46 percent in

2014. Patent- and copyright-intensive industries have seen particularly fast wage growth

in recent years, with the wage premium reaching 74 percent and 90 percent, respectively,

in 2014.

• e educational gap between workers in IP-intensive and other industries observed in

2010 virtually disappeared by 2015. e share of workers in IP-intensive industries with a

bachelor’s degree or higher fell from 42.4 percent in 2010 to 39.8 percent in 2015, whereas

that percentage increased from 34.2 percent to 38.9 percent for workers in non-IP-inten-

sive industries.

• Revenue specic to the licensing of IP rights totaled $115.2 billion in 2012, with 28 indus-

tries deriving revenues from licensing.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae iii

• Total merchandise exports of IP-intensive industries increased to $842 billion in 2014

from $775 billion in 2010. However, because non-IP-intensive industries’ exports in-

creased at a faster pace, the share of total merchandise exports from IP-intensive indus-

tries declined to 52 percent in 2014 from 60 percent in 2010.

• Exports of service-providing IP-intensive industries totaled about $81 billion in 2012 and

accounted for approximately 12.3 percent of total U.S. private services exported in 2012.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae i

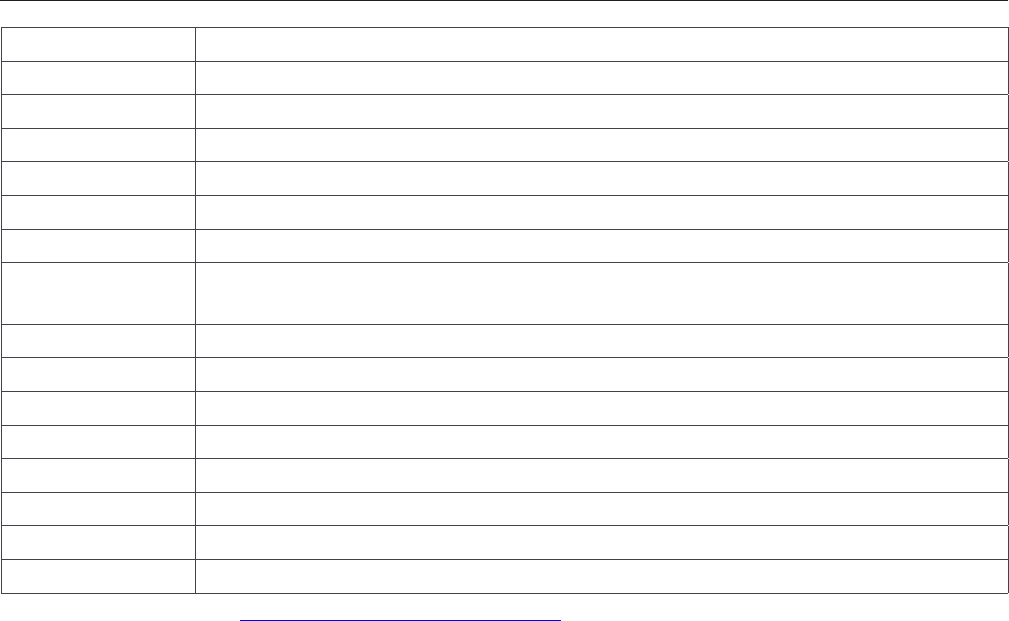

able O Conens

ecuie Summar ..................................................................i

I. Inroducion ......................................................................1

II. he 01 epor and elaed Sudies ...............................................

III. Ideniing IP-Inensie indusries ..................................................

Paens .........................................................................................

rademars .....................................................................................8

Coprighs ......................................................................................9

I. IP-Inensie Indusries in he conom ............................................10

mplomen ................................................................................... 10

oal mplomen Suppored b IP-inensie Indusries .............................................1

IP-Inensie Paroll Jobs b Sae ................................................................ 14

erage ages ................................................................................. 19

ducaion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

alue added ...................................................................................

IP eenue .....................................................................................

oreign rade ...................................................................................

. Conclusion ......................................................................0

ppendi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Paens .........................................................................................1

racional s. hole Paens Couns ..............................................................1

Mehodolog ..................................................................................

rademars ....................................................................................4

rademar Inensi ............................................................................

op 0 rademar egisering Companies .......................................................8

andom Sample o ll rademar egisraions ...................................................9

Coprighs .....................................................................................46

Combined is o IP-inensie indusries ..........................................................4

NCS ......................................................................

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

I. Inroducion

“Whether through the music or movies that inspire us, the literature that moves

us, or the technologies we rely on each day, ingenuity and innovation serve as the

foundation upon which we will continue to grow our economies and bridge our

cultural identities.”

— President Barack Obama, April 26, 2016

Innovation and creative endeavors are indispensable elements that drive economic growth and

sustain the competitive edge of the U.S. economy. e last century recorded unprecedented im-

provements in the health, economic well-being, and overall quality of life for the entire U.S. pop-

ulation as technological innovation in medicine and groundbreaking scientic advances in many

elds were realized.

2

Tremendous advances in worker productivity boosted individuals’ earning

capacity. is allowed consumers to purchase and enjoy the abundant supply of new products

and increasingly diverse creative works of art. As goods and services became more accessible,

they were distinctively marked so buyers could readily select products that meet their individual

preferences.

Intellectual property (IP) has been a vital instrument for achieving such advances throughout our

nation’s history. A growing number of U.S. and international studies demonstrate the important

role of IP in economic activity. is report shows that IP-intensive industries continue to be a

major, integral and growing part of the U.S. economy. We nd that the 81 industries designated

as IP-intensive directly accounted for 27.9 million jobs and indirectly supported an additional

17.6 million jobs in 2014. Together, this represented 29.8 percent of all jobs in the U.S. e total

value added by IP-intensive industries amounted to 38.2 percent of U.S. GDP and IP-intensive

industries paid 47 percent higher weekly wages compared to other industries. Further, at $842

billion the merchandise exports of IP-intensive industries made up 52 percent of total U.S. mer-

chandise exports. Exports of service-providing IP-intensive industries totaled about $81 billion

in 2012, accounting for 12.3 percent of total U.S. private exports in services.

IP incentivizes the creation of new goods and services by conferring exclusive rights to their

creators. While inventions typically are a product of ingenious endeavors that require long, per-

sistent, and meticulous eort, subsequent duplication and use of such innovations are oen less

costly. Patents add to the incentive that inventors have to invest in costly research and develop-

ment (R&D) by providing the opportunity to reap the rewards of their innovations. In the words

of Abraham Lincoln, the patent system “added the fuel of interest to the re of genius in the

discovery and production of new and useful things.”

3

Similarly, copyrights provide the frame-

work that incentivizes authors to create literary, artistic, musical, dramatic, cinematic, and other

works by granting them the exclusive right to engage in the activities that derive economic bene-

2 Gordon 2016.

3 Nicolay and Hay 1905, 113.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

ts from their work. us, patents and copyrights serve as tools to stimulate individual, rm, and

industry level entrepreneurial ventures that feed into economic activities nationwide.

To further exploit the potential of their competitive advantage, producers need eective ways

to indicate to consumers the reliability of their products’ source. A trademark “makes eective

competition possible in a complex, impersonal marketplace by providing a means through which

the consumer can identify products which please him and reward the producer with continued

patronage.”

4

Patents, trademarks, and copyrights are the principal means for establishing ownership rights

to the creations, inventions, and brands that can be used to generate tangible economic benets

to their owner. In 2012, the Department of Commerce issued a report titled Intellectual Proper-

ty and the U.S. Economy: Industries in Focus. Produced jointly by the Economics and Statistics

Administration (ESA) and the United States Patent and Trademark Oce (USPTO), the report

aimed to identify the industries that rely most heavily on patents, trademarks, or copyrights as

IP-intensive and estimate the contribution of those industries to the U.S. economy. It generated a

substantial amount of interest in the IP community, both domestically and abroad, and motivat-

ed other agencies and organizations to produce similar studies investigating the use and impact

of IP across countries, industries, and rms.

is update of the 2012 report has two purposes. First, we duplicate the methodology of the 2012

report to examine how the economic contribution of U.S. IP-intensive industries has evolved.

Second, we review related studies that have been completed since 2012, and discuss the contribu-

tions of the dierent methods. e latest results bolster the 2012 ndings, conrming — across a

range of methodologies — the importance of IP in the economy. In fact, the relative contribution

of IP-intensive industries generally increased in the last several years. We describe these and oth-

er results in more detail in Section IV below.

is report attempts to understand the ways in which IP is used across dierent industries. Our

methodology aims to measure the intensity of IP use, but does not directly measure the extent to

which IP incentivizes the creation of new goods and services. We nd dierences in employment,

wages, value added, and other outcomes that are correlated with IP use, although our method-

ology does not permit us to attribute those dierences to IP alone. As in any area of research, no

single study will yield the complete picture.

is is why it is important for policy-makers and researchers to consider multiple methodologies

for understanding how IP functions in the economy. We are encouraged that other organizations,

agencies, and governments have been energized to replicate, extend, or supplement the work

done in the 2012 report. Taken together, these contributions signicantly advance our knowledge.

Persistent research with a solid empirical foundation will continue to provide the evidence upon

which good policy can rest. e evidence to date demonstrates that IP is an important part of a

robust and growing economy.

4 Smith v. Chanel, Inc. 402 F.2d 562, 566 (9

th

Cir. 1968).

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

II. he 01 epor and elaed Sudies

It is instructive to evaluate the methodology and results of the 2012 report in the context of the

related research completed since the rst report’s release. e 2012 report identied IP-intensive

industries, and compared those industries to other industries across a number of dierent di-

mensions. e methodology consisted of identifying IP-intensive industries based on the use of

IP. According to that report, intellectual property protection aects commerce throughout the

economy by:

• Providing incentives to invent and create;

• Protecting innovators from unauthorized copying;

• Facilitating vertical specialization in technology markets;

• Creating a platform for nancial investments in innovation;

• Supporting entrepreneurial liquidity through mergers, acquisitions, and IPOs;

• Supporting licensing-based technology business models; and

• Enabling a more ecient market for trading in technology and know-how.

All of these mechanisms combine to determine the value of IP to individuals and rms and the

contribution of IP to the economy. Analyzing and measuring all the ways in which IP impacts

the economy is beyond the scope of any individual report. However, a number of studies quanti-

fying the economic impact of IP-intensive rms have emerged since the publication of the 2012

report. We are encouraged to see continued interest in research that builds upon, challenges, and

provides alternative methodologies to the 2012 report.

is section reviews a selected group of studies that targeted similar research questions to the

2012 report and which were published aer that time. e European Patent Oce and the Oce

for Harmonization in the Internal Market (OHIM) published a comparable report in 2013 using

European Union (EU) data.

5

6

It relies on similar methodologies to identify intellectual proper-

ty rights (IPR) intensive industries in Europe and quanties their contribution to the European

economy in the 2008–2010 period. e study nds that IPR-intensive industries generated €4.7

trillion worth of economic activity, which amounted to almost 39% of EU GDP. Furthermore, the

study nds that IPR-intensive industries directly employed 56.5 million Europeans, which ac-

counted for almost 26% of all jobs for the period. e similarity in the ndings serves to further

reinforce the core message of the 2012 report that IP-intensive industries are an integral part of

the economy.

While these reports quantify the contribution of IP-intensive industries in the economy, there is

justied skepticism as to how accurately the employment and value added outcomes can be at-

5 AsofMarch2016,OHIMisknownastheEuropeanUnionIntellectualPropertyOfce.

6 EPO and OHIM 2013.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

tributed to IP itself. For example, the fact that we observe signicant employment in IP-intensive

industries does not inform us about the contribution of IP to economic growth because employ-

ment in non-IP-intensive industries is a viable alternative. e reports also study the wage dier-

entials between IP-intensive and non-IP-intensive industries. Both reports show that IP-intensive

industries pay higher wages than other industries. While this wage premium is noteworthy, we

cannot conclude that the wage dierential is due to IP.

In 2015, OHIM issued a second report, relying on rm-level data to compare rms that own

IPRs to those that do not.

7

e report considers a representative sample of over 130,000 Euro-

pean rms and studies their economic outcomes, taking into account whether they own patents,

trademarks, or designs. e study nds that IPR-owning rms earn, on average, 29 percent more

in revenue per employee and pay, on average, 20 percent more in wages. is dierence is even

more signicant for small and medium enterprises that own IPRs as they earn 32 percent more

in revenue, on average, per employee compared to their counterparts with no IPRs. While this

study does not identify the causal impact of IPRs, it provides detailed evidence of a high correla-

tion between IPR-ownership and economic performance.

e methodology in the 2015 OHIM study addresses a limitation in the way the earlier reports

dened IP-intensive industries. e previous reports measure IP-intensity at the industry-level

based on the aggregate volume of IP relative to employment. ey then designate an industry

as IP-intensive or non-IP-intensive based on whether the IP to employment ratio falls above or

below the average for all industries. ere are reasonable, alternative measures of IP intensity;

including a ratio of IP to gross output, research and development, or value added. But data lim-

itations, such as data sensitivity and the absence of legal requirements on producers to record

and report on internal activities, preclude access to data at the level of detail needed to systemat-

ically employ such measures. e 2015 OHIM report successfully overcomes these limitations by

developing detailed IP-to-rm data necessary for conducting a disaggregated analysis comparing

IPR-owning with non-IPR-owning rms in Europe.

USPTO and U.S. Census researchers have recently constructed patent-to-rm data to enable

similar analysis for the U.S.

8

e authors match data on owners and inventors of U.S. patents

issued between 2000 and 2011 to U.S. Census Bureau data on rms and workers. Using this com-

prehensive database, the authors analyze patent-intensive rms and their contribution to the U.S.

economy. ey nd that patenting rms represent only 1 percent of U.S. rms (2000–2011) but

are among the largest in the economy, accounting for 33 percent of employment. Patenting rms

create more jobs than their non-patenting counterparts of the same age across all age categories

except the very youngest (rms <1 year old). e authors also nd that most patenting rms are

small businesses. But, because they patent less frequently, the majority of U.S. patents are held by

a few large, prolic patenting rms. Lastly, they nd that while the manufacturing sector is par-

7 OHIM 2015.

8 Graham et al. 2015.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

ticularly patent intensive with more than 6 percent of rms owning a patent between 2000 and

2011, the majority of patenting rms are in the services and wholesale sectors.

A handful of recent academic papers have also attempted to measure the impact of IP on rm

performance. One recent notable contribution uses detailed USPTO data to study whether pat-

ents have a causal impact on the growth potential of startups.

9

e authors nd that patents do in

fact “help startups create jobs, grow their sales, innovate, and eventually succeed” and that a delay

in a patent grant can retard the benet of each of these.

10

11

Another line of research uses surveys to study the role that IP plays in the economic performance

of rms as well as their innovative eorts. A recent study surveys over 6,000 American manufac-

turing and service sector rms to evaluate the extent to which rms that introduce new products

in the market outsource innovation to specialized rms. It nds that between 2007 and 2009, 16

percent of manufacturing rms introduced a new product in their industry. Of these innovators,

42 percent reported patenting their most signicant new product, though there is considerable

variation across industries and rms. More R&D-intensive industries, i.e., those with above

average share of rms investing in R&D, tend to patent new products at higher than average

rates. Roughly 63 percent of large manufacturing rms reported patenting their most signicant

new product innovation, compared to only 47 percent of medium rms and 36 percent of small

rms.

12

e UK Intellectual Property Oce published another survey based study in 2012 that aims to

quantify the extent to which patents increased expenditure in R&D. Using data from the UK in-

novation survey and linked data on rm performance, the authors estimate the patent prot pre-

mium, meaning the additional returns to R&D that can be attributed to patent protection.

13

ey

nd that patent premiums are positive and provide incentives to invest in R&D, though estimates

vary by type of rm and industry. Estimated patent premiums are lower for smaller rms and

rms outside biotech and pharmaceutical industries. However, premium and incentive eects are

comparable for young and older rms, indicating that patent protection can incentivize R&D for

new as well as established innovators.

9 Farre-Mensa et al. 2016. By employing an instrumental variables approach, the authors are able to identify a causal

relationship, as opposed to a mere correlation.

10 Ibid., 2.

11 Note that some startups may prefer a delay in patent grant because a larger share of its overall economic value may be

realized later in the patent term or during the period of time that is accrued due to patent term adjustment.

12 Arora et al. 2016.

13 Arora et al. 2012.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

Taken together, these contributions signicantly advance our knowledge about the role of IP in

the economy. An important direction of future work is exploiting even more granular data and

seeking methods to identify causal links between IP and economic performance. Survey based

studies, which can be designed to target specic research questions, will also continue to improve

our understanding about the extent to which IP contributes to the economy. And it is critical that

policy-makers consider scientic research standards when evaluating evidence with policy mak-

ing implications.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

III. Ideniing IP-Inensie indusries

As in the 2012 report, IP-intensity for an industry is dened as the count of its intellectual prop-

erty for a given period of time relative to the industry’s total employment. An industry is desig-

nated as IP-intensive if its IP-count to employment ratio is higher than the average for all indus-

tries considered. Dividing IP-counts by employment is one approach to adjust for dierences in

industry size, which makes industries more comparable. However, there are other alternatives.

For instance, IP-counts could be normalized by capital holdings, research and development ex-

penditures, value added, or gross output. In addition, other methods are available for dierenti-

ating between IP-intensive and non-IP-intensive industries.

14

To maintain consistency and allow

comparisons to the 2012 report, this update follows the methodologies applied previously but

expands coverage to the 2009–2013 period.

15

Paens

e USPTO grants utility, plant, and design patents that give the grantee the right to exclude

“others from making, using, oering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the United

States or importing the invention into the Unites States.”

16

Using the U.S. Patent Classication

(USPC) scheme, patents are classied in over 450 patent “technology classes” that distinguish

their inventive content.

17

18

e USPTO maintains a general concordance between its technology

classications and 30 North American Industry Classication (NAICS) codes. e concordance

enables analysts to associate utility patents with these NAICS coded industries.

19

We rely on

NAICS-based patent counts for 2009 to 2013 to identify patent-intensive industries.

20

is ap-

proach strictly limits the patent analysis to the manufacturing sector because the concordance

only associates patents with manufacturing industries. Non-manufacturing industries, such as

construction, utilities, and information, may rely on utility patents, but these industries are not

captured by the patent-NAICS concordance. We calculate a measure of industry patent “intensity”

dened as the ratio of total patents over the ve years in a NAICS category to the average payroll

14 For example, analyzing the differences by deciles or even evaluating a continuous function are possible alternative

approaches that may prove informative.

15 Detailed description of the methodology is provided in the Appendix.

16 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(1).

17 Utilitypatentsmaybeclassiedintomorethanonetechnologyclassbutareorganizedaccordingtotheirprimaryclas-

sication.

18 Whileitdoesnotaffectanyoftheresultsinthisreport,itisworthnotingthatofcialuseoftheUSPCwasdiscontin-

uedinJanuaryof2015.PatentsarenowclassiedusingtheCooperativePatentClassication(CPC)scheme.

19 ThisconcordancewascreatedbytheUSPTOwithnancialsupportfromtheNationalScienceFoundation.Becauseno

similar concordances to NAICS are available for plant or design patents, only utility patents are used in our analysis.

Seewww.uspto.gov/web/ofces/ac/ido/oeip/taf/all_tech.htmformoreinformationonutilitypatents.Foranoverview

of NAICS, see www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/index.html.

20 Seewww.uspto.gov/web/ofces/ac/ido/oeip/taf/data/misc/patenting_trends/info_ptrends2008.txt.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

employment by industry.

21

Because employment reects the overall size of an industry, dividing

patent counts by employment normalizes patenting activity with respect to industry size.

22

is

approach evens the playing eld, so that the most patent-intensive industries are dened not as

the ones with the most patents, but rather as those with the most patents per worker.

Nearly all the industries identied as patent-intensive in the 2012 report are also designated as

such for the 2009–2013 period. One industry, resin, synthetic rubber, bers, and articial and

synthetic bers and laments (NAICS 3252), did not make the cuto in the current report. In

addition, some changes occurred in the rank-order of these industries. For example, semiconduc-

tor and other electronic components (NAICS 3344) was previously designated as the third most

patent-intensive industry, but dropped to h place. However, based on the close similarity in

the list and rank-order of patent-intensive industries across reports, it appears that patent-inten-

sity at the industry level is quite persistent over time.

23

rademars

A trademark is dened as “a word, phrase, symbol, or design, or a combination thereof, that iden-

ties and distinguishes the source of the goods of one party from those of others.”

24

rough ex-

clusive rights of use, trademarks confer legal protection that enables companies to communicate

to consumers the quality characteristics of their products and services and recoup investments

therein.

As in the 2012 report, this study uses three dierent approaches to identify trademark-intensive

industries.

25

e rst approach, as with patents, measures the trademark-intensity of an industry

based on the ratio of trademark counts to employment and designates those industries with an

above average ratio as trademark-intensive. Starting with the complete set of trademark regis-

trations, we matched publicly traded companies by their name to a separate database containing

information on the rms’ primary industry and number of employees. ese data allowed us to

calculate trademark intensity by industry for the matched rms. e second approach uses the

USPTO’s listing of top 50 trademark registering companies (which, unlike the rst approach,

include both private and public companies) from the Performance and Accountability Reports

for 2009–2013 and identies industries that appear repeatedly as trademark-intensive. To expand

coverage for privately-held companies and for smaller and younger rms, the third approach

draws a random sample of 300 registrations from the 194,326 trademark registrations in 2013.

We assign NAICS industry codes to the U.S. registrants in the sample and calculate the industry

share of total registrations, labeling those with an above average share as trademark-intensive.

21 Usingave-yearperiod(inthiscase,years2009–13)insteadofjustoneyearhelpsminimizethechancethatanoma-

lies in any given year will skew our results.

22 Value added and gross output are two alternative gauges of industry size; however, estimates at the level of detail need-

edforthisanalysisarenotavailableduetodatacondentialitylimitations.

23 A detailed discussion of the methodology and a table of results are provided in the Appendix.

24 U.S.PatentandTrademarkOfce2016.Weusethetermtrademarktoencompassbothtradeandservicemarks.

25 These methodologies are discussed in detail in the Appendix.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

We combine the results from each approach to form the nal group of trademark-intensive in-

dustries.

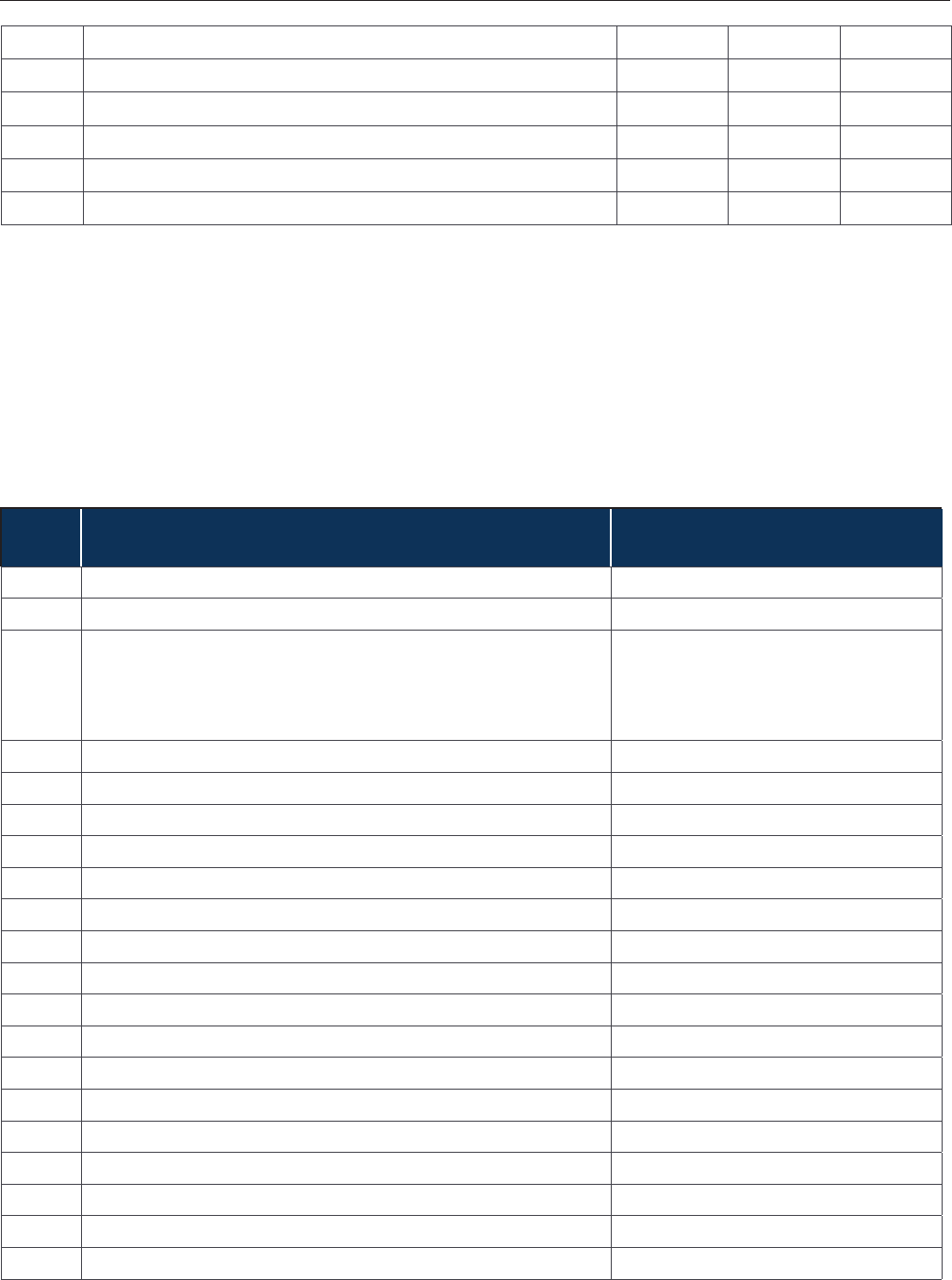

e results from these exercises, which are summarized in Tables A-6, are noteworthy in at least

two ways. First, the diversity of the industries listed as trademark-intensive is indicative of both

the spread and intensity of trademark use. Second, we observe signicant consistency across the

three methodologies in the industries designated as trademark-intensive; which provides some

evidence on the validity of these approaches.

For robustness, we also compare the nal group to the industries covered by the companies in In-

terbrand’s listing of Best Global Brands in 2013.

26

As discussed in the Appendix, these two groups

overlapped signicantly further corroborating our ndings.

Coprighs

e 1976 Copyright Act of the U.S. states that copyright protects “original works for authorship

xed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they

can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a

machine or device.”

27

Copyright-intensive industries were rst dened by the World Intellectual

Property Organization’s (WIPO) Guide on Surveying the Economic Contribution of the Copy-

right-based industries and subsequently applied to the U.S. Economy.

28

As in the 2012 report,

this update uses a narrower denition of copyright-intensive industries than WIPO, focusing

on industries that produce creative works and excluding several industries associated with the

distribution of copyrighted material. We dene copyright-intensive industries as those primarily

responsible for the creation or production of copyrighted materials. is group includes nearly all

industries traditionally associated with production of creative works.

29

26 Interbrand 2013.

27 17 U.S.C § 102(a).

28 World Intellectual Property Organization 2003. See, for example, Siwek 2009.

29 A more detailed description of our methodology is provided in the Appendix.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

IV. IP-Inensie Indusries in he conom

mplomen

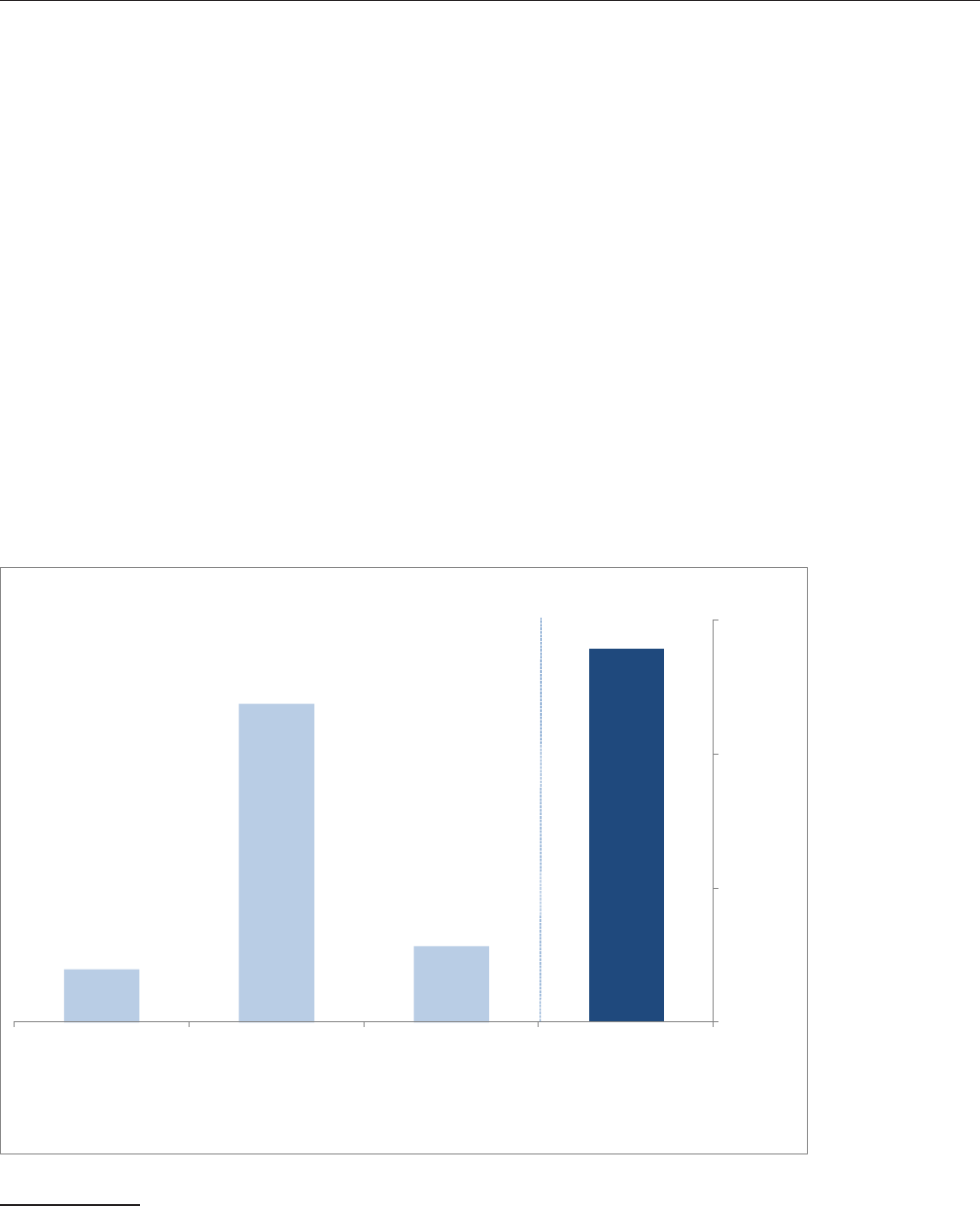

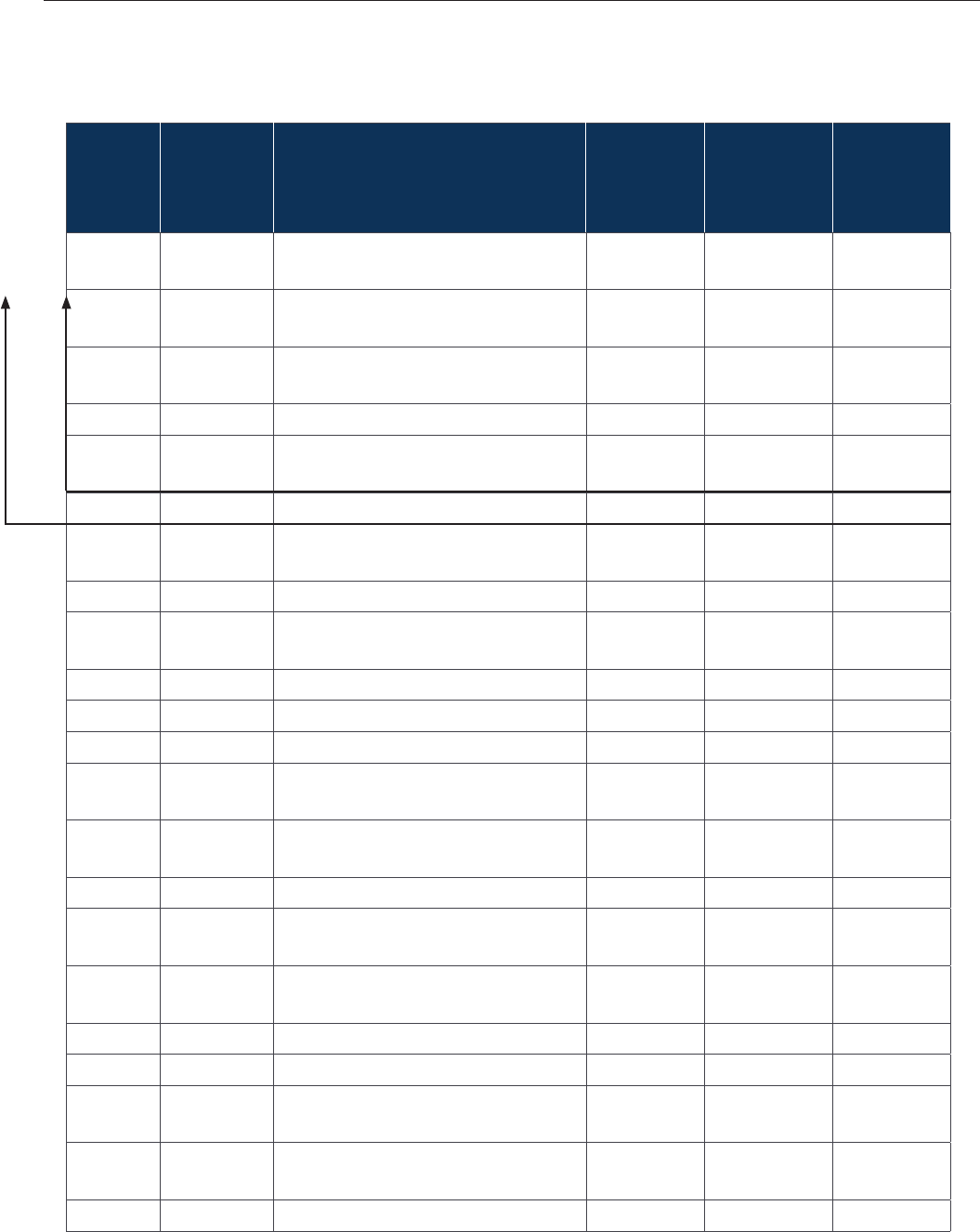

Employment in IP-intensive industries totaled 27.9 million in 2014, representing 18.2 percent

of all jobs in the economy (See Figure 1). Since the 2012 report, employment in IP-intensive

industries has generally increased, rising from 27.1 million in 2010. However, due to employ-

ment growth in non-IP-intensive industries, IP-intensive industries account for a slightly lower

overall percentage of U.S. jobs (down from 18.8 percent in 2010). As in the 2012 report, trade-

mark-intensive industries contribute the most to employment. ese industries accounted for

23.7 million jobs in 2014 (up from 22.6 million in 2010), or 85 percent of all IP-intensive jobs (up

from 83 percent in 2010).

30

Copyright-intensive industries supplied 5.6 million jobs (compared

to 5.1 million in 2010) followed by patent-intensive industries with 3.9 million jobs (3.8 million

in 2010). Twenty-three of the 81 industries considered in this report were intensive in more than

one form of IP protection. For instance, Audio and Video Equipment Manufacturing (NAICS

3343) is both patent-intensive and trademark-intensive. ese multi-intensity industries account-

ed for 5.5 million jobs (up from 4.5 million jobs for 24 industries in 2010).

31

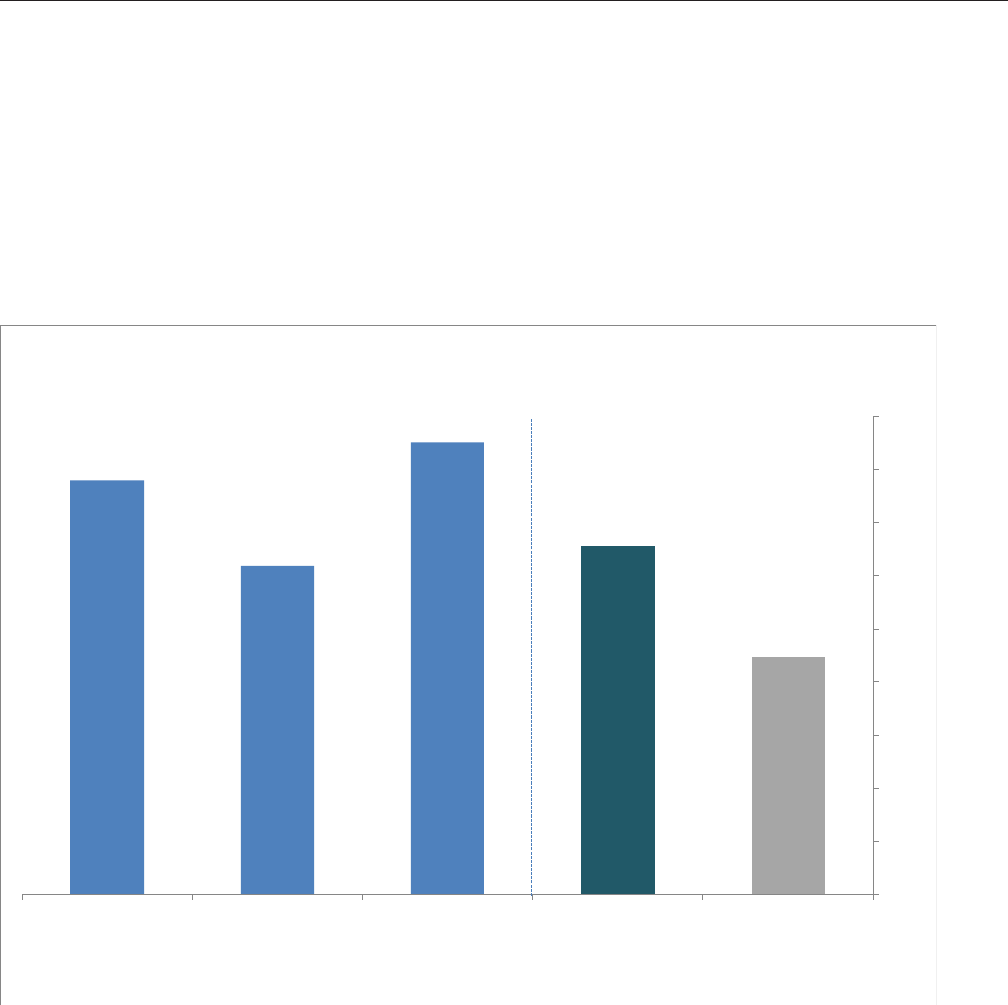

3,927

23,741

5,672

27,877

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

Patent-intensive Trademark-intensive Copyright-intensive IP-intensive

Jobs in thousands

Figure 1. Employment in IP-Intensive Industries, 2014

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Industry Productivity program.

Note: Estimates include wage and salary employment, the self-employed, and unpaid family workers. Because several industries

were found to be trademark-intensive and patent- or copyright-intensive, total employment in IP-intensive industries is less

than the sum of employment in patent-, trademark-, and copyright-intensive industries.

30 The fact that 66 out of the 81 IP-intensive industries are trademark-intensive industries likely explains why these

industries continue to account for a large majority of IP-intensive industries employment.

31 Because some industries are intensive in more than one form of IP, the sum across the individual groups is larger than

thetotalforIP-intensiveindustries.The5.5milliongurecanbecalculatedbysubtractingoverallIPintensiveem-

ployment from the sum of employment of trademark, patent, and copyright intensive industries.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

Self-employed individuals make up a signicant portion of jobs in IP-intensive sectors, partic-

ularly in copyright-intensive industries. Self-employed individuals accounted for 2.4 million

jobs in 2014 (unchanged from 2010); which amounts to 8.5 percent of IP-intensive industries

employment (compared to 8.9 percent in 2010). By contrast, the self-employed share of jobs in

non-IP-intensive industries dropped to 7.2 percent in 2014 from 8.8 percent in 2010

(See Figure 2).

At the individual IP level, the share of self-employed has exhibited relatively small changes since

2010. Trademark-intensive industries increased their share from 7.3 percent in 2010 to 7.6 per-

cent in 2014, while patent- and copyright-intensive industries dropped to 2.0 percent (from 2.2

percent) and 15.4 percent (from 16.5 percent), respectively. e fact that copyright-intensive

industries continue to have the highest self-employment share is not surprising as many jobs

in the creative and performing arts are contract rather than payroll jobs, usually related to the

completion or performance of a specic authored work. However, it should also be noted that

trademark-intensive industries continue to have the largest number of self-employed persons at

1.8 million.

2.0%

7.6%

15.4%

8.5%

7.2%

0%

4%

8%

12%

16%

20%

Patent-intensive Trademark-intensive Copyright-intensive IP-intensive Non-IP-intensive

Figure 2. Self-Employed Share of All Jobs in IP-Intensive Industries, 2014

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Industry Productivity program.

Note: Estimates show the self-employed and unpaid family workers as a share of all jobs. However, unpaid family workers account for

only about one percent of the combined total of the self-employed and unpaid family workers outside of agriculture.

The IP-intensive bar on the right represents all IP-intensive (patent-, trademark- and copyright-intensive) industries.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

Figure 3 shows the trends in employment growth across IP and non-IP-intensive industries over

the past twenty-ve years. As noted in the 2010 report, employment in IP-intensive industries

was nearly the same in 2010 as in 1990 because considerable growth in employment during the

1990s was largely reversed in the 2000s. Since 2010, however, jobs in these industries rebounded.

From 2010 to 2014, IP-intensive industry employment grew 6 percent, driven by trademark and

copyright-intensive industries. Patent-intensive industries showed moderate job growth follow-

ing the Financial Crisis, but this may reect the fact that patent-intensive industries are restricted

to manufacturing. Since 2010, employment in non-IP-intensive industries outpaced that of IP-in-

tensive industries by 2 percentage points. As a result, the share of total employment in IP-inten-

sive industries edged down over the past two and half decades from 21.0 percent in 1990 to 20.6

percent in 2000 and 18.2 percent in 2014.

60

80

100

120

140

160

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014

1990 = 100

Figure 3. Indexed Employment in IP-Intensive Industries, 1990-2014

Copyright-intensive

Non-IP-intensive

IP-intensive

Trademark-intensive

Patent-intensive

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Industry Productivity program.

oal mplomen Suppored b IP-inensie Indusries

While IP-intensive industries directly accounted for 27.9 million jobs either on their payrolls

or under contract in 2014, they also helped to support an additional 17.6 million jobs in other

(non-IP-intensive) industries that supply them goods and services (i.e. the supply chain). Taken

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

together, IP-intensive industries directly and indirectly supported 45.5 million jobs, about thirty

percent of all employment.

32

Figure 4 shows direct employment in IP-intensive industries (medium blue bar) along with in-

direct employment in the supply chain (the rectangle below the blue bar). Indirect employment

increased for all IP-intensive industries with trademark-intensive industries growing the most

since 2010. Trademark-intensive industries indirectly employed 17.3 million jobs in 2014, up

from 13.1 million in 2010. Copyright-intensive industries supported an additional 2.8 million

jobs indirectly in 2014, compared to 2.5 million in 2010. Patent-intensive industries indirectly

supported 3.5 million jobs, up slightly from 3.3 million in 2010.

3,507

17,307

2,809

17,602

3,988

23,741

5,733

27,877

7,495

41,048

8,542

45,478

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

Patent-intensive Trademark-intensive Copyright-intensive IP-intensive

Jobs in Thousands

Figure 4. Total Employment Supported by IP-Intensive Industries, 2014

Total employment

supported by the

IP-intensive industries

=

Jobs in patent,

trademark, copyright, or

IP-intensive industries

+

Supply-chain jobs

in other industries

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis' Industry Accounts office and the Bureau of

Labor Statistics' Industry Productivity program.

Note: Estimates include wage and salary employment, the self-employed, and unpaid family workers. Because several industries

were found to be trademark-intensive and patent- or copyright-intensive, total employment in IP-intensive industries is less than

the sum of employment in patent-, trademark-, and copyright-intensive industries.

32 These estimates are derived from unpublished input/output tables computed and analyzed by staff from the Bureau

ofEconomicAnalysis’IndustryAccountsofce.DataareconsistentwiththeDecember2010annualrevisiontothe

annualInput-Outputtablesandarebasedonthe2014after-redenitiondomesticmakeandusetablesandestimatesof

theshareof2014employmentattributabletonaldemandinIP-intensiveindustries.Totaloutputrequirementtables

were calculated based on the make and use table following the methodology published in the mathIO.doc, which are

available at www.bea.gov/industry/zip/cxctr2002detail.zip. In the previous report, non-IP employment was calculated

using employment data from BEA. In this update employment measures come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’

IndustryProductivityprogram:http://www.bls.gov/lpc/lpc_hours_and_employment.xlsx.NAICScodesareconverted

toindustrycodesusing:http://www.bea.gov/industry/xls/GDPbyInd_VA_NAICS_1997–2012.xlsx.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

As in the 2012 report, patent-intensive industries rely more heavily on the supply chain as evi-

denced by a larger share of total jobs in indirect employment (47 percent) compared to trade-

mark- and copyright-intensive industries.

In addition to the indirect employment supported through the supply chain, IP-intensive indus-

tries also help support downstream businesses that facilitate the distribution and trade of goods

and services. If one were to include indirect employment in these businesses, total employment

supported by IP-intensive industries would be greater than the 45.5 million jobs mentioned

above.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

IP-Inensie Paroll Jobs b Sae

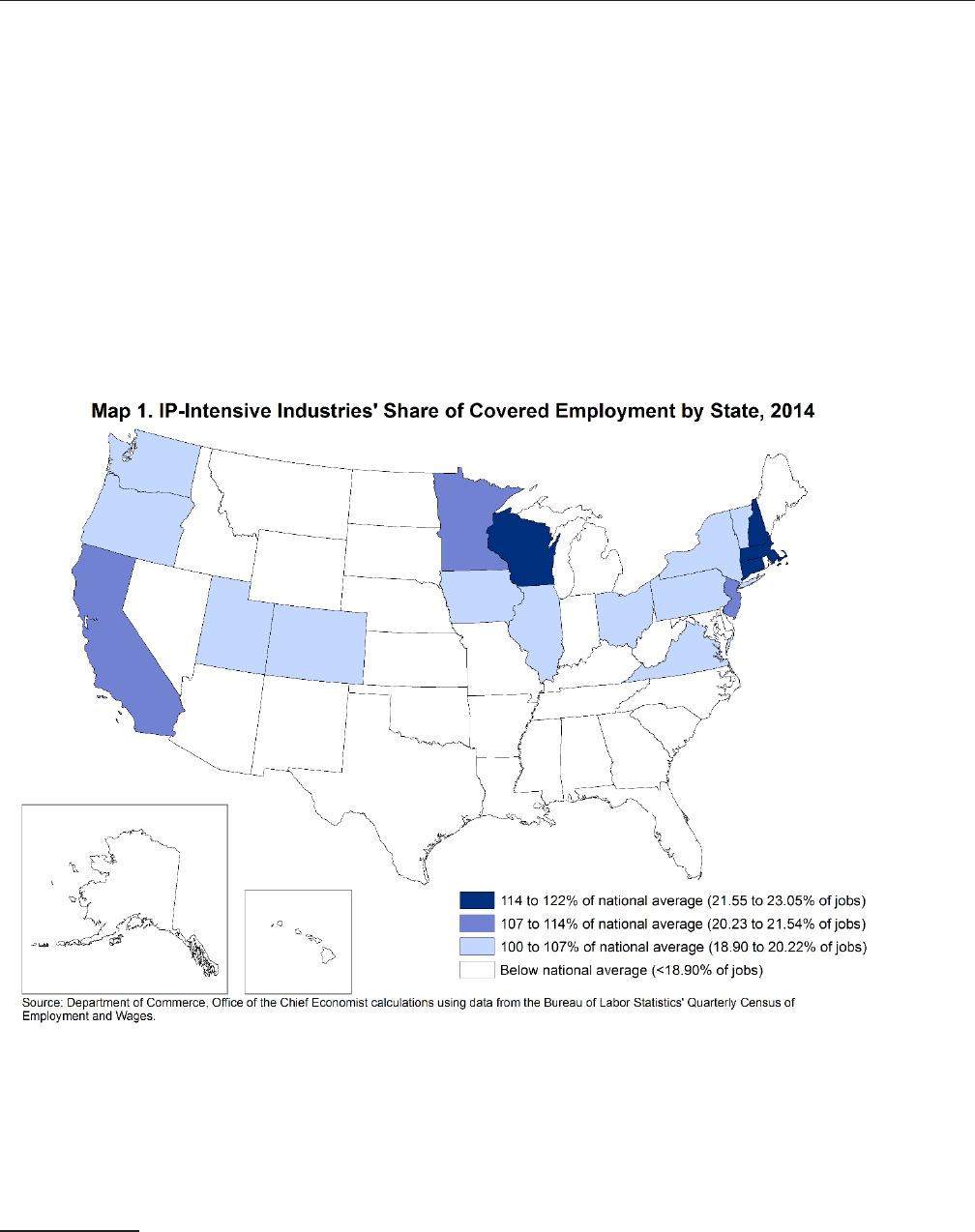

Employment in IP-intensive industries is not evenly distributed across states. Map 1 highlights

those U.S. states that are above the national average in terms of the share of covered employment

in IP-intensive industries.

33

Eighteen states (up from 16 in 2010) exceeded the national average

of 18.9 percent, which was 19.1 percent in 2010. With a few exceptions, IP-intensive states cluster

in New England, the upper Midwest, and West Coast. is is broadly similar to the distribution

reported in the 2012 report. e top ve states are also similar. In 2014, they were New Hamp-

shire (23.1 percent), Connecticut (23.0 percent), Wisconsin (22.5 percent), Massachusetts (21.9

percent), and Minnesota (21.2 percent). Vermont, which was part of the top ve in 2010, was

replaced by Minnesota.

33 The data used to examine state employment are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment

and Wages (QCEW) and measure covered employment. Covered employment refers to jobs covered by state and fed-

eral unemployment insurance law, which represent practically all of civilian wage and salary employment. These data

do not include the self-employed or unpaid family workers. For more information on QCEW, see www.bls.gov/cew.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

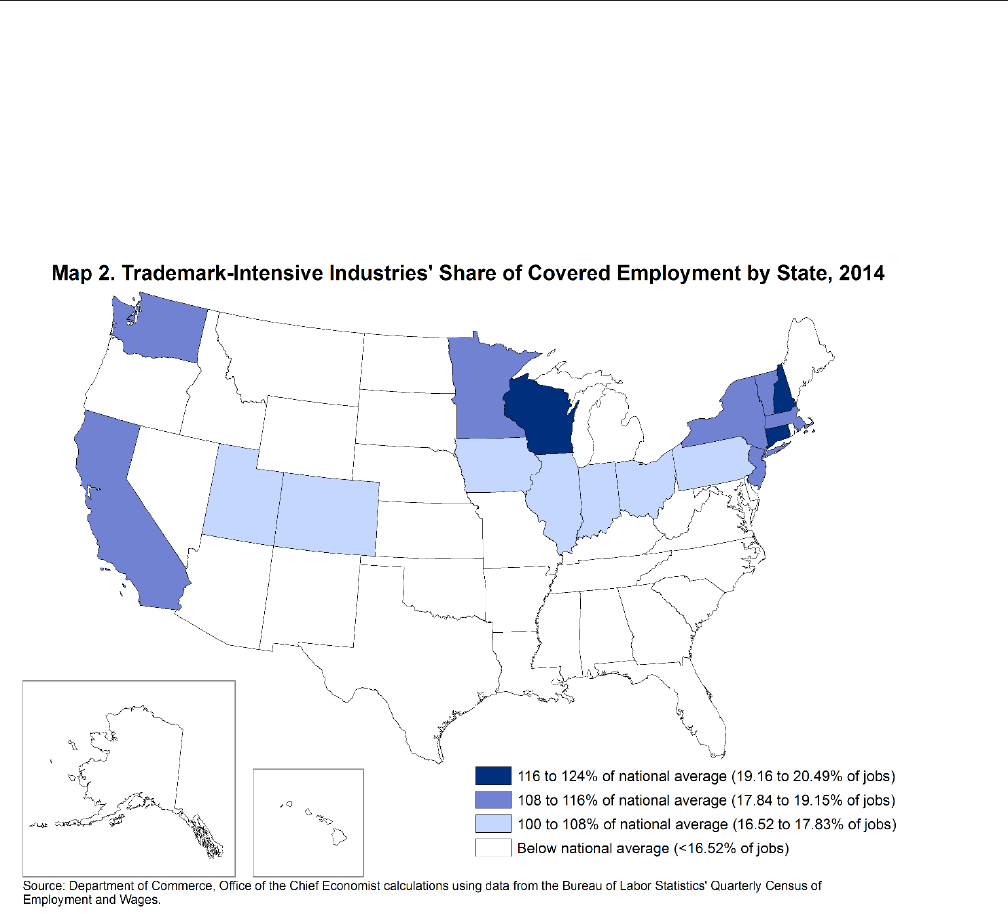

As seen in Map 2, the state distribution for trademark-intensive industries looks like what is ob-

served in Map 1 for all IP-intensive industries. Sixteen of the 18 states with above-average shares

of IP-intensive jobs also had above-average shares of trademark-intensive jobs. is reects the

contribution of trademark-intensive industries to IP-intensive jobs and the fact that 66 of the 81

IP-intensive industries were designated as trademark-intensive. Only Virginia and Oregon do not

show up as trademark-intensive employment states.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

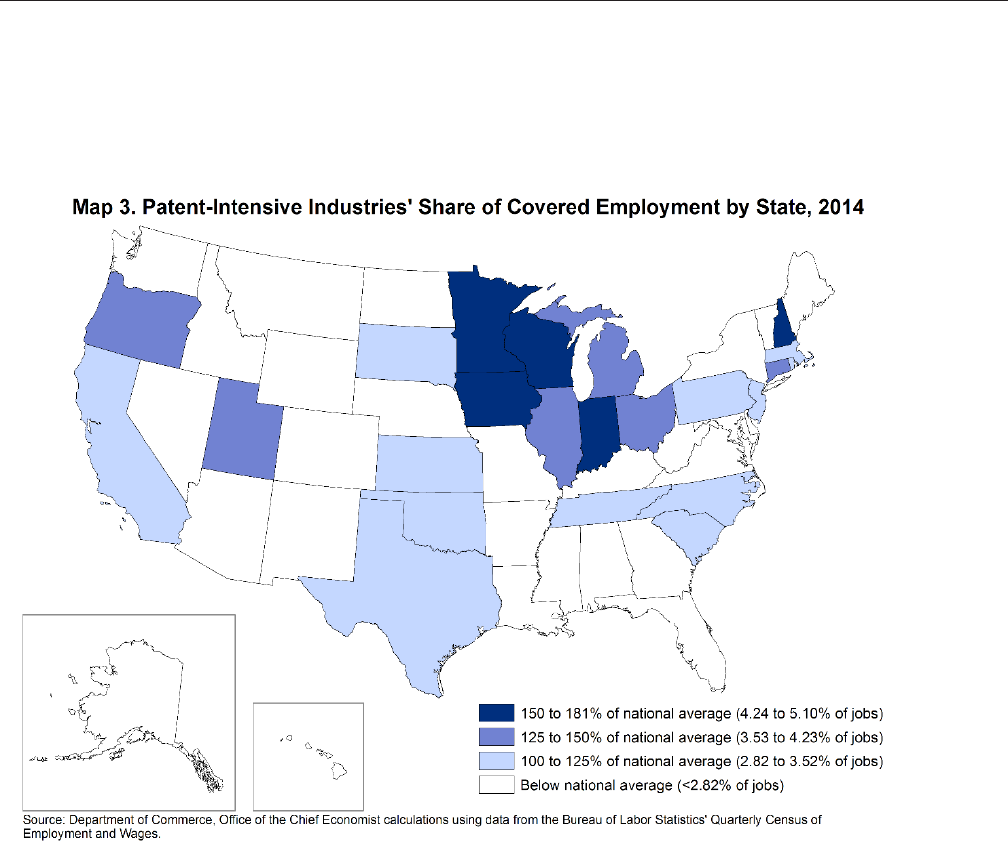

In 2014, 23 states had above-average shares of employment in patent-intensive industries, up

from 21 states in 2010 (See Map 3). Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas were added in 2014 while Ver-

mont was removed. States in New England and the upper Midwest continue to have the highest

shares.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

For copyright-intensive industries in 2014, 14 states had above-average employment shares and

11 of these appeared on the 2010 list. Minnesota was removed from the list, while Illinois and

New Hampshire were added. As in the previous report, these states are mostly spread along the

East and West coasts. (See Map 4.)

Overall, ve out of the six states that had above-average employment shares for patent-, trade-

mark-, and copyright-intensive industries in 2010 also did in 2014. ese are California, Con-

necticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Utah. Even more, Oregon and Washington became

IP-intensive states in 2014. e inclusion of Oregon is due to the increased share of its patent-in-

tensive industries while the inclusion of Washington is due to the increased share of its trade-

mark-intensive industries. ese results suggest the use of intellectual property is expanding

geographically.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

erage ages

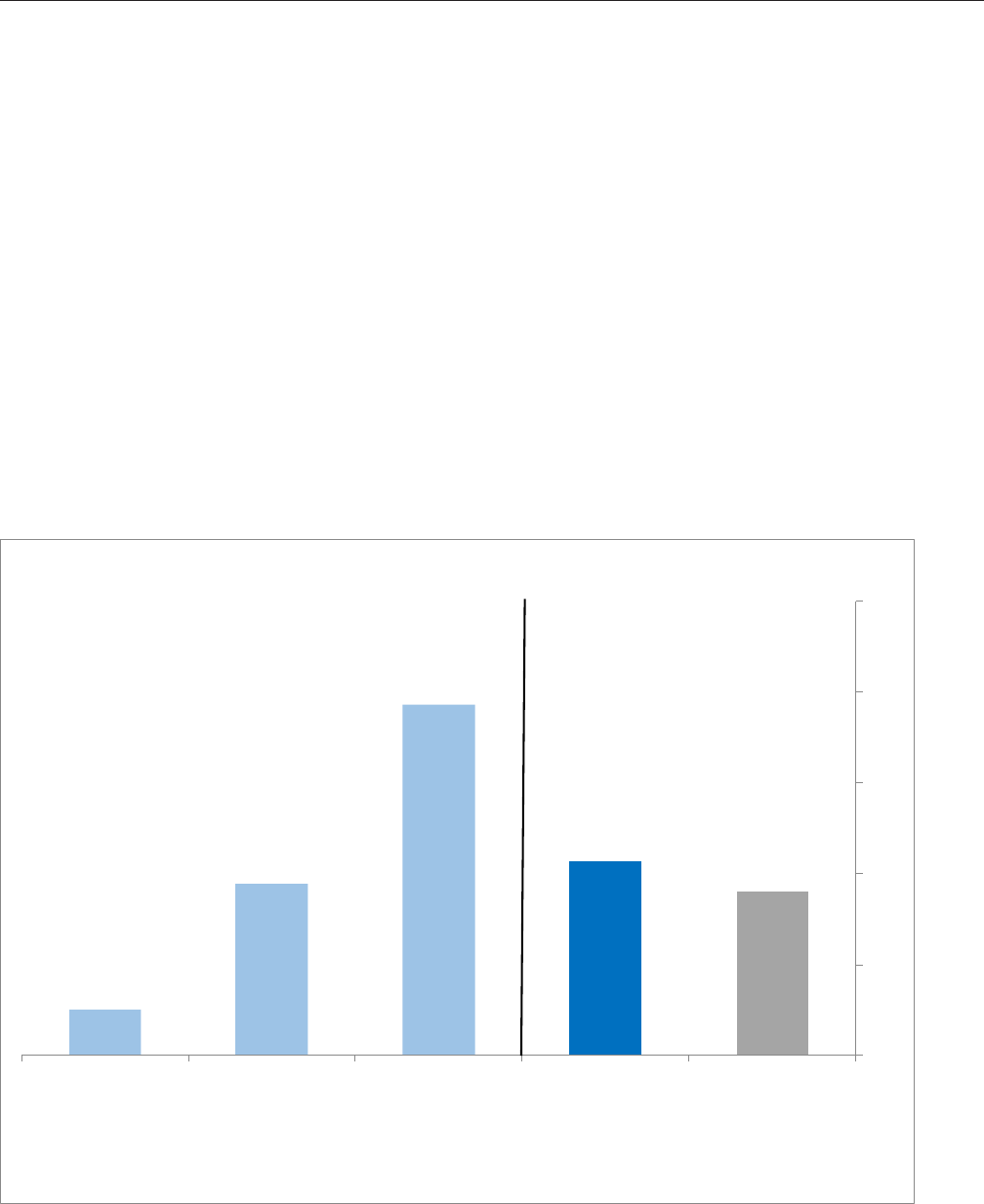

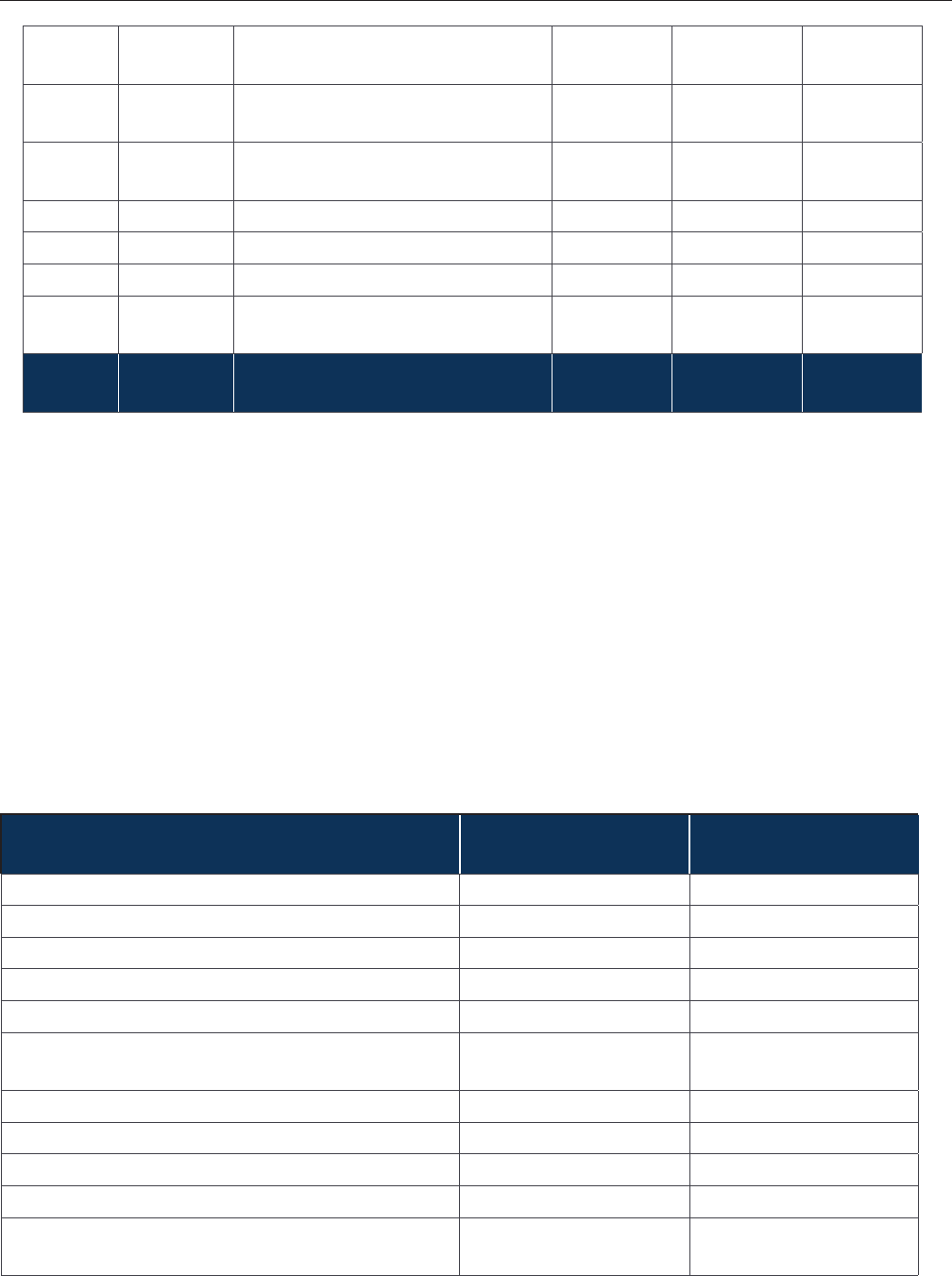

Private wage and salary workers in IP-intensive industries continue to earn signicantly more

than those in non-IP-intensive industries. In 2014, the average weekly wage of $1,312 was 46

percent higher (up from 42 percent in 2010) than for workers in non-IP-intensive industries (See

Figure 5). While workers in non-IP-intensive industries earned $896 per week, those in patent-

and copyright-intensive industries earned $1,560 and $1,701 per week, respectively. At $1,236 per

week, workers in trademark-intensive industries earned less than their counterparts in patent-

and copyright-intensive industries, but still 38 percent more than non-IP-intensive workers.

$1,560

$1,236

$1,701

$1,312

$896

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

$1,600

$1,800

Patent-intensive Trademark-intensive Copyright-intensive IP-intensive Non-IP-intensive

Figure 5. Average Weekly Wages of Private Wage and Salary Workers in

IP-Intensive Industries, 2014

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

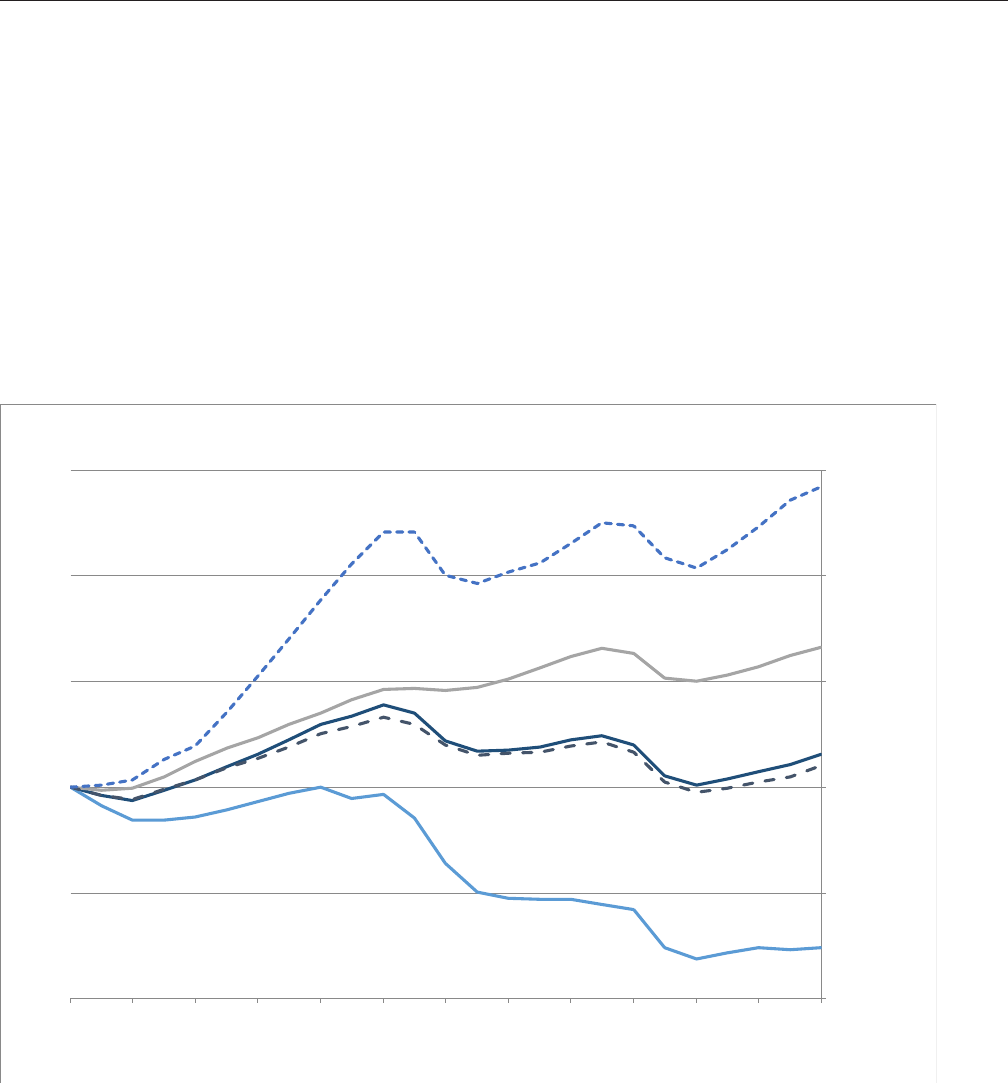

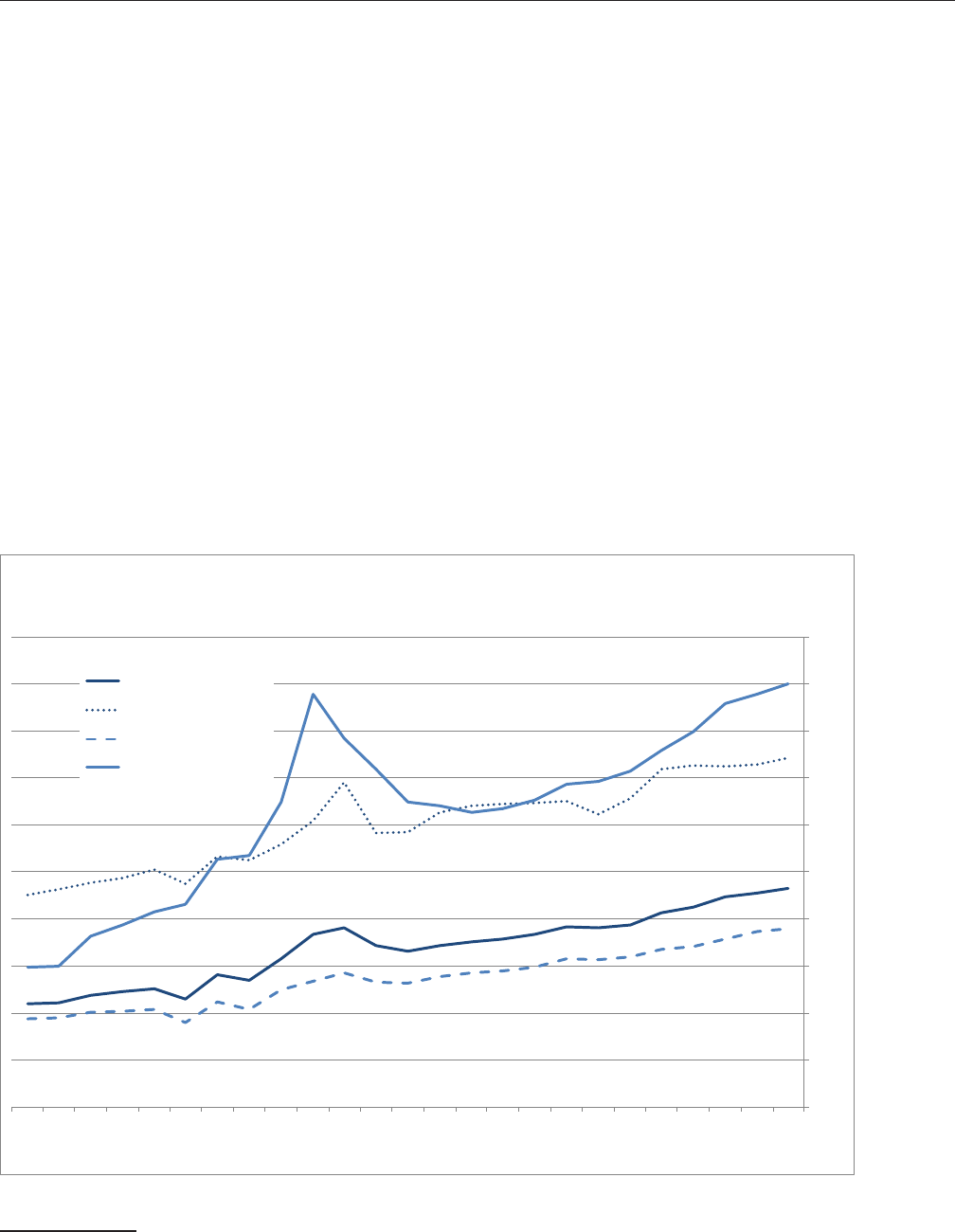

Figure 6 plots the trends in wage premiums for workers in IP-intensive industries.

34

With some

notable volatility, these premiums have generally increased. In the decade aer 1990, the premi-

um for workers in IP-intensive jobs increased from 22 to 38 percent. It lost some ground early in

the 2000s but has been rising steadily since 2002. By 2014, the IP-intensive industry wage pre-

mium stood at 46 percent. e trademark-intensive industry subgroup followed a similar path.

In 1990, trademark-intensive industries paid 19 percent more with this premium climbing to

29 percent by 2000 and 38 percent by 2014. Wages in the patent-intensive industries started at a

45 percent premium and grew through the 1990s before surging up to 69 percent by 2000. is

surge was reversed in 2001 and held fairly at in the last decade before rising again since 2008. In

2014, the average wage premium for patent-intensive workers was 74 percent.

e wage premium in copyright-intensive industries experienced a more extreme version of the

trends discussed above. In 1990, workers in these industries earned 30 percent more than non-IP

intensive industry workers, on average. is premium tripled during the following decade to 88

percent by 1999. Over the next ve years, it decreased to 63 percent before growing again to 90

percent by 2014. e wage premium for all four sets of industries was higher in 2014 than at any

point over the prior 24 years.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014

Figure 6. Average Weekly Wage Premium of Workers in IP-Intensive

Industries Relative to Non-IP-Intensive Industries, 1990-2014

IP-intensive

Patent-intensive

Trademark-intensive

Copyright-intensive

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

34 The wage premium measures the percentage difference between the wages of workers in IP-intensive industries versus

those in non-IP-intensive industries. It is a premium because average weekly wages are higher in IP-intensive indus-

tries.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

ducaion

In competitive labor markets, wages are closely correlated to worker productivity, and education-

al attainment is a common gauge of workers’ skill and expected productivity. us, we expect

employees in IP-intensive industries to have relatively high educational attainment. e 2010

data were consistent with this hypothesis as 42.4 percent of workers age 25 and older in IP-inten-

sive industries had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 34.2 percent in private non-IP

intensive industries.

35

However, data from the 2015 Current Population Survey show this edu-

cation gap virtually disappeared (See Figure 7). e share of workers in IP-intensive industries

with a bachelor’s degree or higher fell to 39.8 percent in 2015, whereas that percentage increased

to 38.9 percent for workers in non-IP-intensive industries. Besides the increase in educational

attainment among workers in non-IP-intensive industries, trademark-intensive industries con-

tributed to the narrowing of the educational attainment gap. In 2015, the share of workers with

college education or higher in trademark-intensive industries fell to 36.6 percent (from 38.8

percent in 2010). By contrast, this share increased to 66.4 percent (from 61.2 percent in 2010) for

copyright-intensive industries and 41.7 percent (from 38.7 percent) for patent-intensive indus-

tries.

5.6

8.6

1.6

7.8

7.7

25.0

27.5

10.3

25.7

25.7

27.6

27.4

21.7

26.7

27.7

27.2

25.7

45.7

27.7

23.8

14.5

10.9

20.7

12.1

15.1

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Patent-intensive Trademark -intensive Copyright-intensive IP-intensive Non-IP-intensive

Figure 7. Distribution of Employed Persons in IP-Intensive Industries

by Educational Attainment, 2015

Graduate

degree

Bachelor's

degree

Some college or

associate

degree

High school

diploma

Less than high

school

Source: Current Population Survey, 2015, Public Use Microdata Files and ESA calculations. Estimates are for employed persons age 25 and over.

35 These estimates are calculated from 2010 and 2015 Current Population Survey public-use microdata, as accessed

through the Census Bureau’s DataFerrett tool at dataferrett.census.gov.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

As was the case in 2010, workers in copyright-intensive industries were the most educated of the

three IP-intensive segments in 2015 with 20.7 percent having attained a graduate degree, and

only 1.6 percent having less than a high school diploma. e share of workers in patent-intensive

industries with at least a bachelor’s degree was smaller, at 41.7 percent, but still higher than the

share for non-IP-intensive industries. In trademark-intensive industries, however, the share of

workers with a college or higher degree fell below that of the non-IP-intensive industries by 2015.

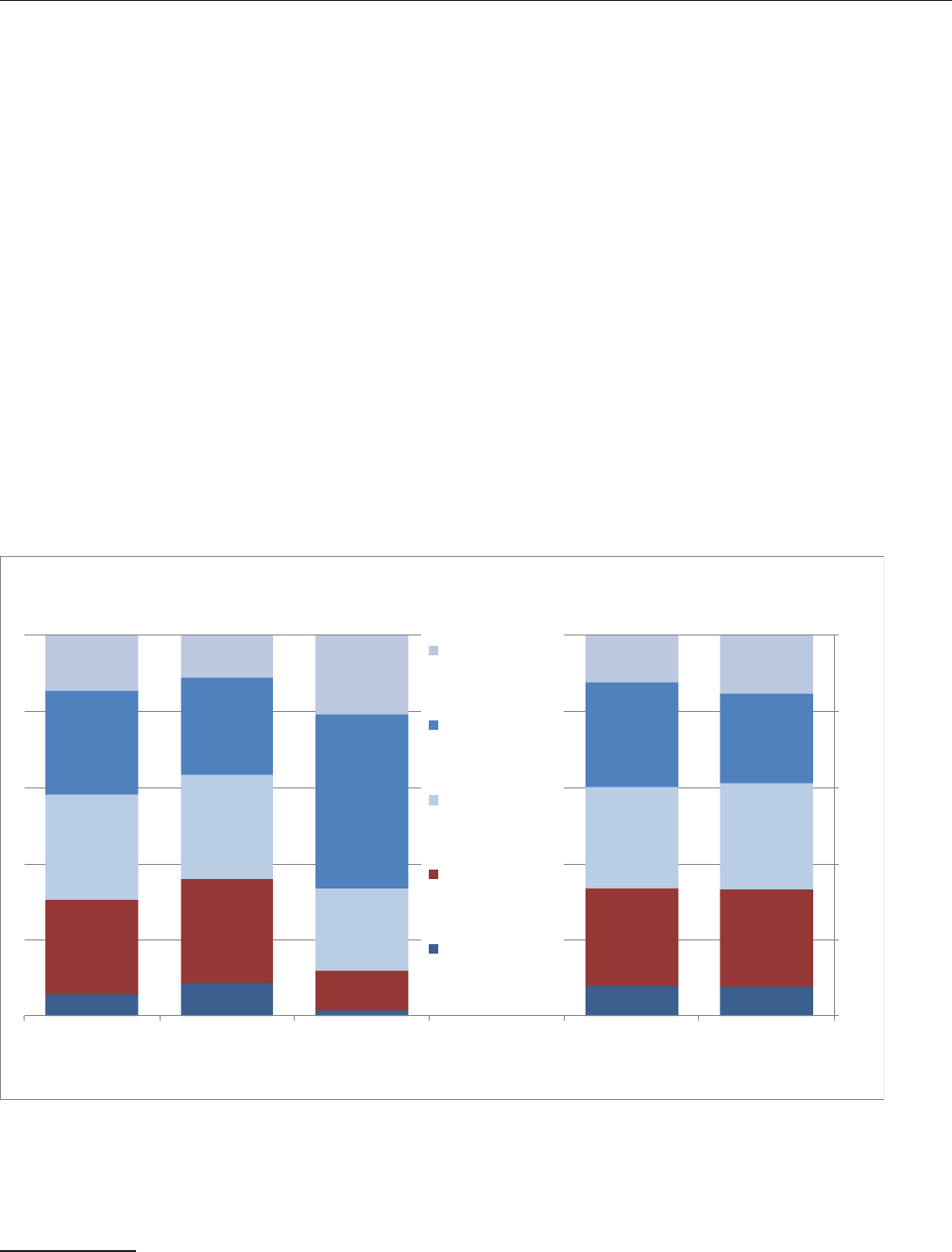

alue added

While jobs in IP-intensive industries increased between 2010 and 2014, jobs in non-IP-intensive

industries grew at a slightly faster pace. Consequently, the proportion of total employment in

IP-intensive industries actually declined to 18.2 percent from18.8 percent in 2010. (See Figure

8) In contrast, the value added by IP-intensive industries increased substantially in total amount

and as a share of GDP between 2010 and 2014. IP-intensive industries accounted for $6.6 trillion

in value added in 2014, up more than $1.5 trillion (30 percent) from $5.06 trillion in 2010. Ac-

cordingly, the share of total U.S. GDP attributable to IP-intensive industries increased from 34.8

percent in 2010 to 38.2 percent in 2014.

Trademark- and copyright-intensive industries appear to be driving the recent growth in value

added. Between 2010 and 2014, the share of GDP attributed to trademark- and copyright-inten-

sive industries increased to 34.9 percent (from 30.8 percent) and 5.5 percent (from 4.4 percent),

respectively. Trademark-intensive industries alone accounted for $6.1 trillion in value added in

2014 (up from $4.5 trillion in 2010). e value added by patent-intensive industries increased

from $763 to $881 billion between 2010 and 2014. However, because this growth trailed the other

IP-intensive segments, the share of GDP attributable to patent-intensive industries declined from

5.3 percent to 5.1 by 2014.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

5.1%

34.9%

5.5%

38.2%

61.8%

2.6%

15.5%

3.7%

18.2%

81.8%

0%

15%

30%

45%

60%

75%

90%

Patent-intensive Trademark intensive Copyright intensive IP-intensive Non-IP-intensive

Figure 8. Value Added and Employment Shares of IP-Intensive Industries, 2014

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts and

the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Industry Productivity program.

Share of employment

Share of GDP

IP eenue

Up to this point, IP-intensity was dened based on the counts of patents, trademarks and copy-

rights per employee at the industry level. While this method adjusts total IP holdings for dier-

ences in industry size, it does not directly measure the revenue associated with using intellectual

property. Using revenue to dene IP-intensity is more restrictive because it requires rights hold-

ers to attribute some portion of total revenue directly to IP holdings, which is dicult due to the

intangible nature of IP assets. Ideally, information would be available on the full revenue stream

attributable to an industry’s intellectual property which would include both the measurable and

unmeasurable contributions of IP. With this information, an alternative IP-intensity metric could

be dened as total IP revenue or IP revenue as a share of total revenue, which is another way to

adjust for industry size.

Although comprehensive information of this type do not exist, the Economic Census of U.S.

business establishments does provide some data on measureable revenues associated with licens-

ing, royalties, and other forms of trade of intellectual property. e Economic Census, which is

conducted every ve years by the U.S. Census Bureau, asks companies to report sales by specic

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

product lines.

36

Ninety-one of these product lines were identied as related to IP.

37

Revenue for

each of the 91 product lines were summed and used to dene an IP-intensity metric based on the

ratio of IP revenue to total revenue at the industry level.

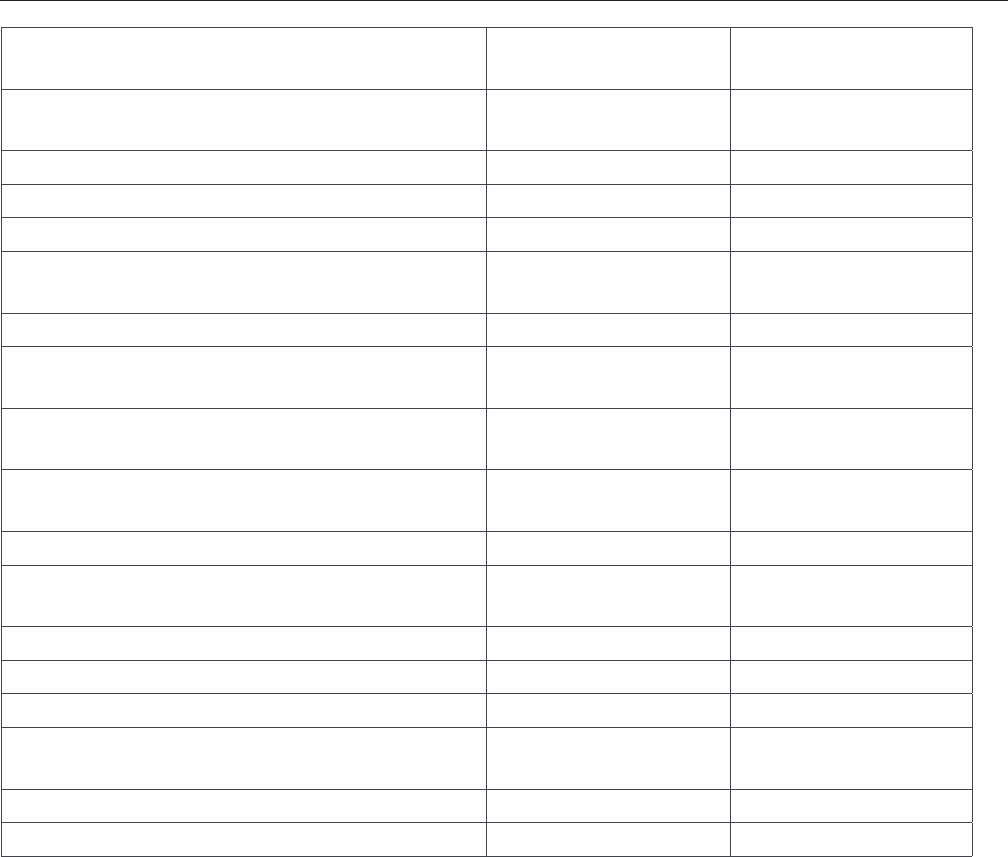

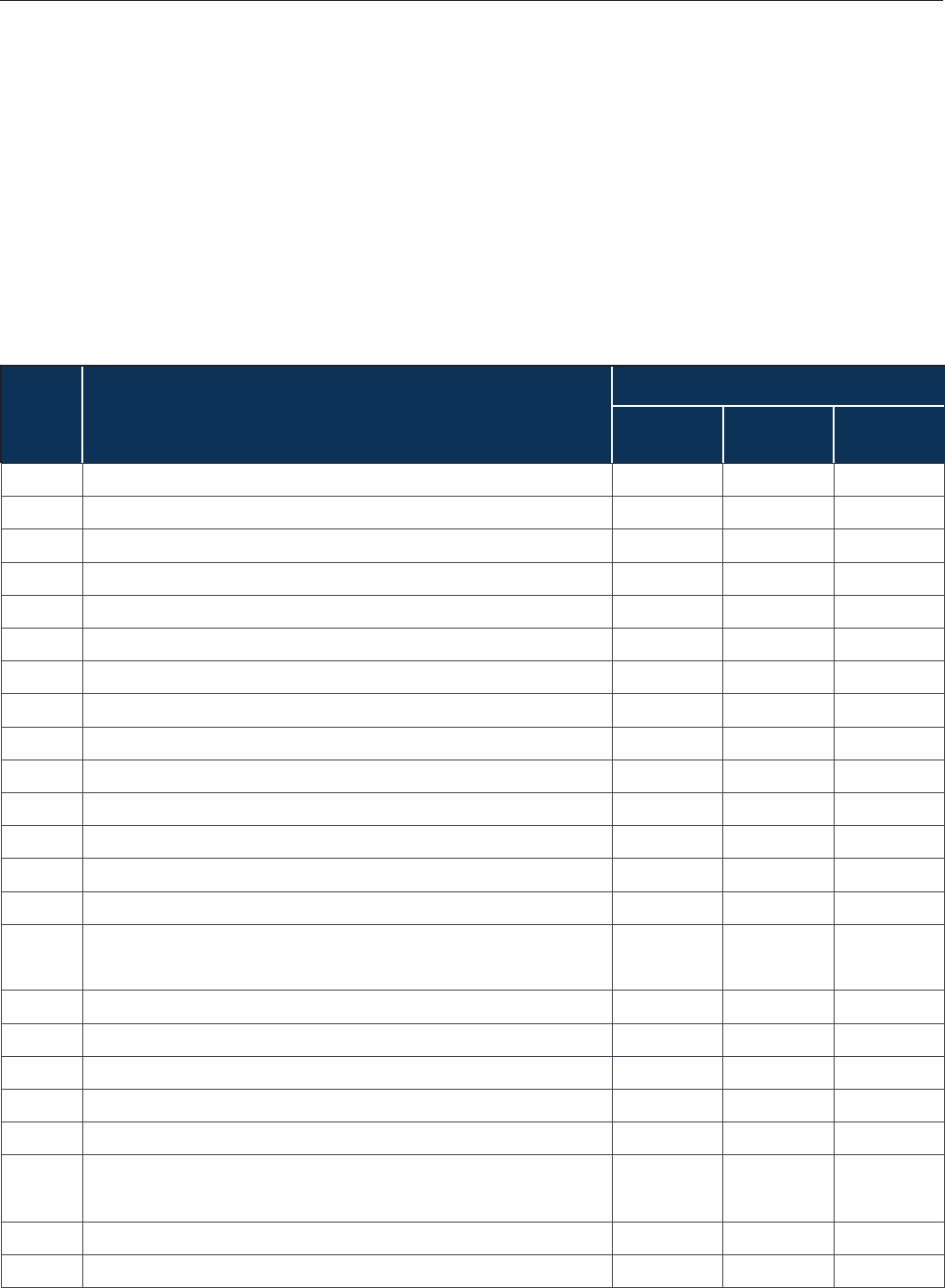

Table 1 shows the 29 four-digit NAICS industries that had some IP-related revenue, ranked by

the IP share of total revenue in 2012. e distribution of IP-related revenue was fairly concen-

trated. Six industries had IP revenue shares above the 11.3 percent average (among industries

for which the Economic Census collected IP-related revenue), and these industries accounted for

about 82 percent of total revenue from IP-related products. All six industries were also identied

as IP-intensive using the IP counts per employee metric.

Overall, 15 of the 29 industries with any IP revenue in 2012 were also classied as IP-intensive

using the IP counts per employee metric. Of the 14 industries that were not previously classied,

ve were in the “other services (except public administration)” sector, four were in the arts, en-

tertainment, and recreation sector, four were in the professional, scientic and technical services

sector, and one was in the information sector.

36 TheEconomicCensusistheU.S.Government’sofcialve-yearmeasureofAmericanbusinessandtheeconomy.It

isconductedbytheU.S.CensusBureauandresponseisrequiredbylaw.Thelatestcensuswascompletedin2012.In

October through December 2012, forms were sent out to nearly 4 million businesses, including large, medium and

small companies representing all U.S. locations and industries. Respondents were asked to provide a range of oper-

ational and performance data for their companies. To learn more about the Economic Census, please see http://www.

census.gov/econ/census/.

TheindustryclassicationsforallestablishmentscoveredbytheeconomiccensusandsurveysarebasedontheNorth

AmericanIndustryClassicationSystem(NAICS).FormoreonIndustryClassicationofEstablishments:

http://www.census.gov/econ/census/help/naics_other_classication_systems/industry_classication_of_establishments.html.

37 Table A-11 in the appendix provides a complete list of these codes.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

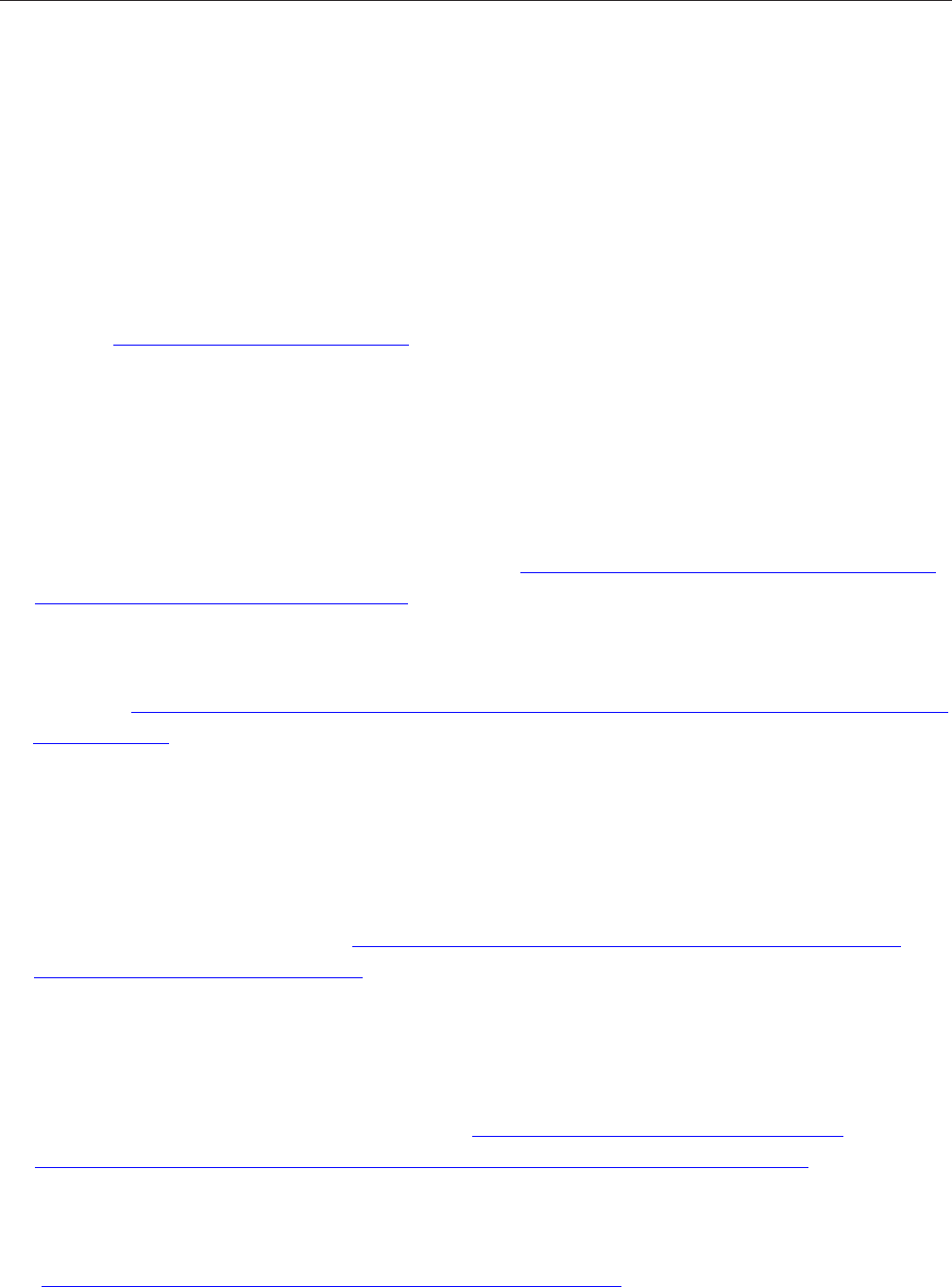

able 1. Indusries ih IP-elaed eenue, aned b IP eenue Inensi, 01

NICS

code

IP-

inensie

Indusr ile

IP-relaed

reenue

$millions

Cumulaie

share

IP-reenue

inensi

IP/oal

reenue

Moionpicureandideo

indusries

essorsononnancialinangible

asses

Independenarissriersand

perormers

Soundrecordingindusries

Cableandohersubscripion

programming

Perormingarscompanies

gensandmanagersorpublic

gures

Oherinormaionserices

Promoersoperormingars

sporsandsimilareens

Specaorspors

adioandeleisionbroadcasing

Proessionalandsimilar

organiaions

Nespaperperiodicalbooand

direcorpublishers

Soarepublishers

Businessschoolsandcompuer

andmanagemenraining

Managemenocompaniesand

enerprises

egalserices

Socialadocacorganiaions

Compuerssemsdesignand

relaedserices

Oherproessionalscienicand

echnicalserices

Ciicandsocialorganiaions

Above mean + 1 std. dev.

Above mean

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

derisingpublicrelaionsand

relaedserices

Museumshisoricalsiesand

similarinsiuions

rchiecuralengineeringand

relaedserices

ran-maingandgiingserices

Oherelecommunicaions

Oherpersonalserices

iredelecommunicaions

carriers

oal

ll indusries ih

IP-relaed reenue 1,684 100.0 11.

Note: Intensity measure is the percent of overall revenue generated for each four-digit NAICS industry from the licensing of

intellectual property protected assets.

Source: ESA calculations using data from the Census Bureau’s 2012 Economic Census.

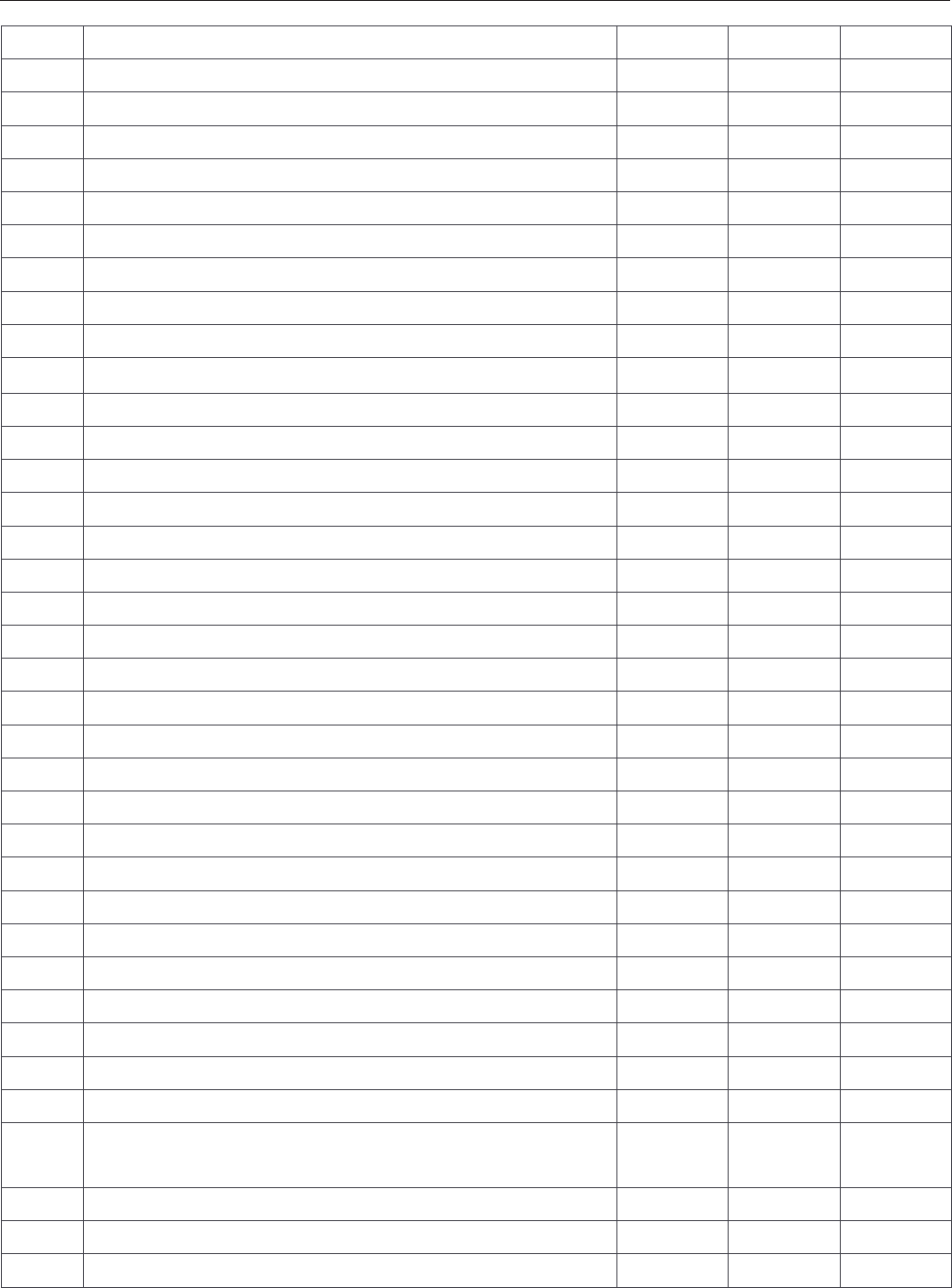

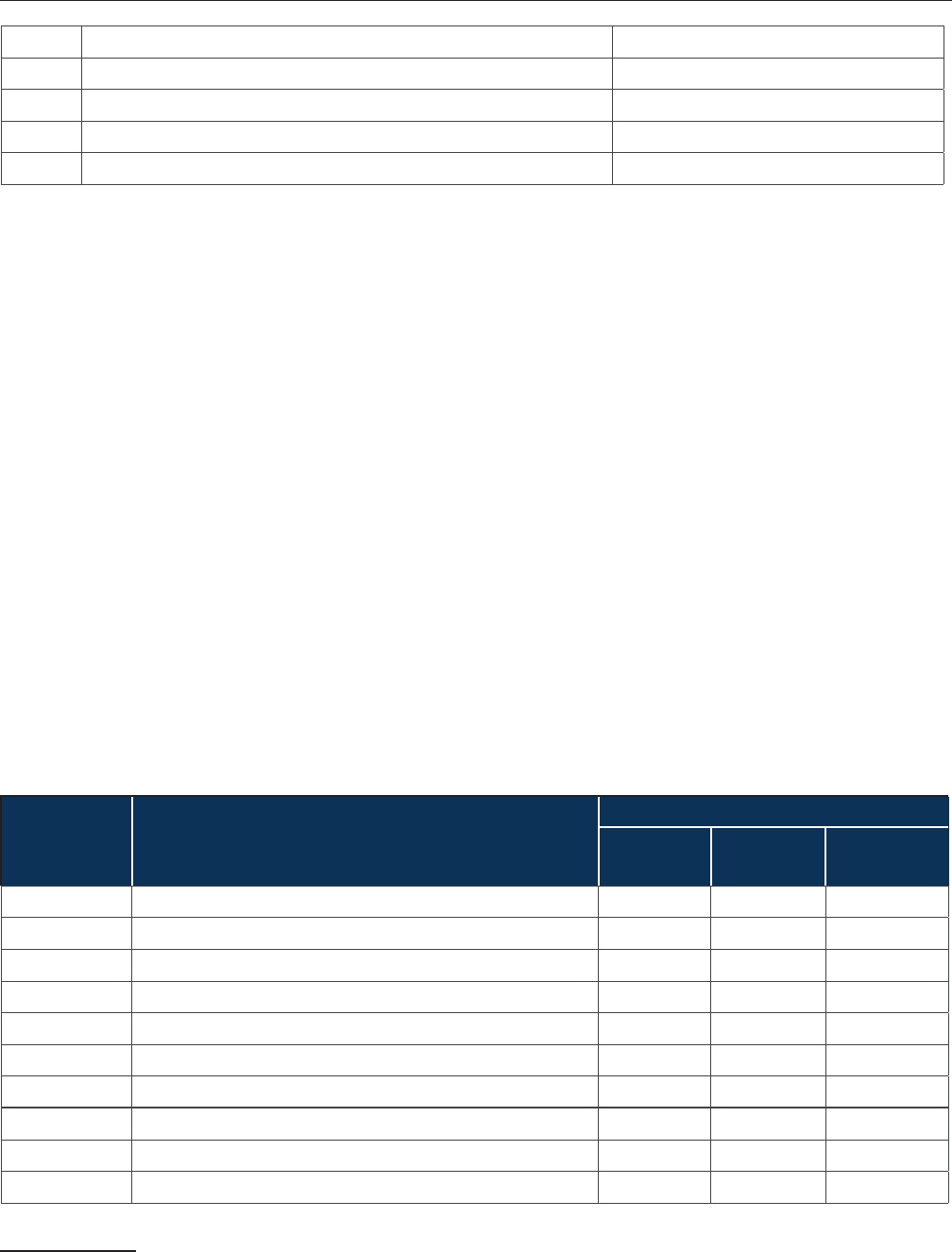

e product line codes in the Economic Census can also be grouped into those that explicitly

mention IP licensing as the source of revenue. As shown in Table 2, revenue specic to the licens-

ing of IP rights totaled $115.2 billion in 2012, with 28 industries deriving revenues from licens-

ing. Among these industries, the motion picture and video industry generated the largest reve-

nue, $41.6 billion in 2012, followed by the cable and other subscription industry and the lessors

of nonnancial intangible assets industry. Not only do these three industries account for nearly

78 percent of all reported direct revenues from IP licensing, they also have the largest shares of

licensing revenue, averaging 50.7 percent of total revenue.

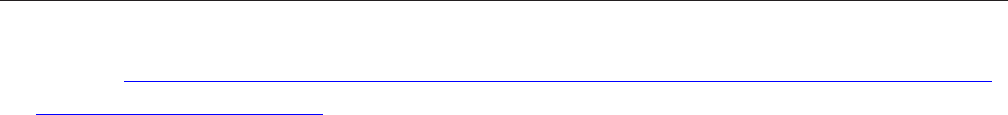

able . IP-licensing eenue b Indusr, 01

NICS code

and indusr ile

IP-licensing reenue

$millions

Share o oal reenue

oal

-Moionpicureandideoindusries

-Cableandohersubscripionprogramming

-essorsononnancialinangibleasses

-Oherinormaionserices

-Scienicresearchanddeelopmen

serices

-Soundrecordingindusries

-adioandeleisionbroadcasing

-Proessionalandsimilarorganiaions

-Soarepublishers

-Independenarissriersand

perormers

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

-Nespaperperiodicalbooanddirecor

publishers

-Compuerssemsdesignandrelaed

serices

-Managemenocompaniesandenerprises

-Specaorspors

-gensandmanagersorpublicgures

-rchiecuralengineeringandrelaed

serices

-Perormingarscompanies

-Promoersoperormingarssporsand

similareens

-derisingpublicrelaionsandrelaed

serices

-Oherproessionalscienicandechnical

serices

-ran-maingandgiingserices

-Businessschoolsandcompuerand

managemenraining

-Socialadocacorganiaions

-Ciicandsocialorganiaions

-iredelecommunicaionscarriers

-Museumshisoricalsiesandsimilar

insiuions

-Oherelecommunicaions

-Oherpersonalserices

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 Economic Census

oreign rade

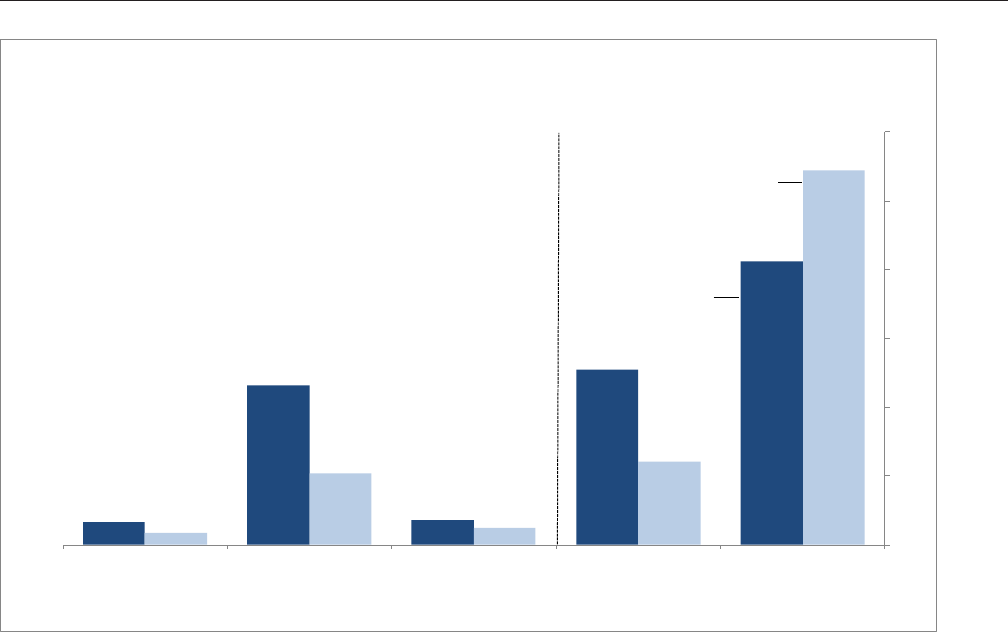

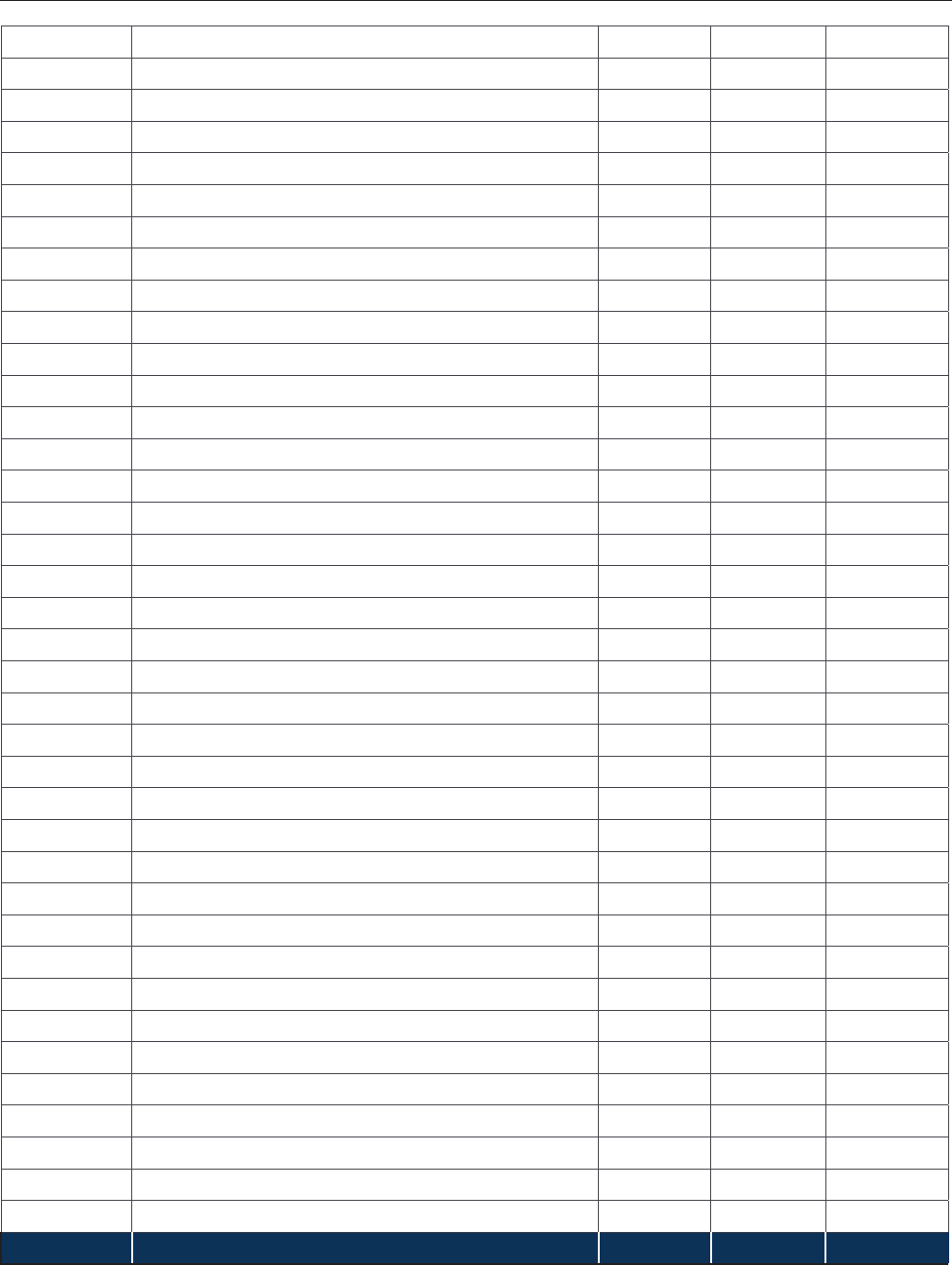

Once again using IP counts per employee to group industries, IP-intensive industries continue to

account for a signicant share of U.S. exports and imports. Total merchandise exports increased

from $775 to $842 billion between 2010 and 2014. However, because exports from non-IP-inten-

sive industries increased at a faster pace, the share of total merchandise exports from IP-intensive

industries declined to 52 percent in 2014 from 60 percent in 2010. e value of merchandise im-

ports into IP-intensive industries totaled $1,391 billion in 2014, which is largely unchanged from

2010, but fell as a percent of overall U.S. merchandise imports from 69.9 to 59.3 percent between

2010 and 2014.

e breakdown of exports by industry for 2014 is very similar to that for 2010. Manufacturing

industries accounted for 96 percent of merchandise exports from IP-intensive industries in 2014,

compared to 99 percent in 2010. Oil and gas extraction and nonmetallic minerals sectors account-

ed for the rest in both years. Within manufacturing, exports from the basic chemicals sector led

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

the way, increasing from $58.4 to $64.5 billion between 2010 and 2014. Exports from the semi-

conductors and other electronic components sector, which topped the chart at $64.0 billion in 2010,

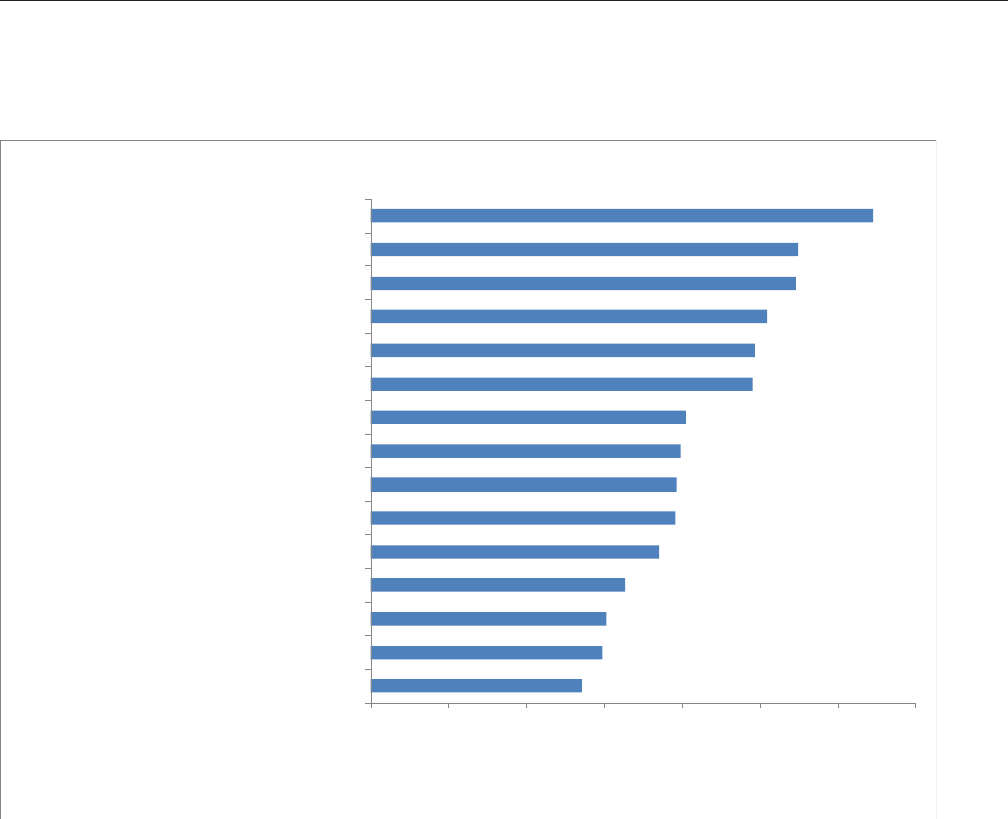

fell to $54.8 billion in 2014. (See Figure 9)

$27.1

$29.8

$30.3

$32.6

$37.0

$39.1

$39.2

$39.8

$40.5

$49.1

$49.3

$50.8

$54.5

$54.8

$64.5

$0 $10 $20 $30 $40 $50 $60 $70

Other Electrical Equip & Components

Oil & Gas

Engines, Turbines & Power Transmsn Equip

Medical Equip & Supplies

Nonferrous (exc Alum) & Processing

Ag & Construction & Machinery

Other General Purpose Machinery

Resin, Syn Rubber, Artf & Syn Fibers/fil

Communications Equipment

Computer Equipment

Misc Manufactured Commodities

Navigational/measuring/medical Instrument

Pharmaceuticals & Medicines

Semiconductors & Electronic Components

Basic Chemicals

Figure 9. Merchandise Exports of Selected IP-Intensive Industries, 2014

Billions of current dollars

Source: ESA

calculations

using data from the Census Bureau's Foreign Trade Division.

Note: The selected industries accounted for 76.5 percent of merchandise exports of IP-intensive industries.

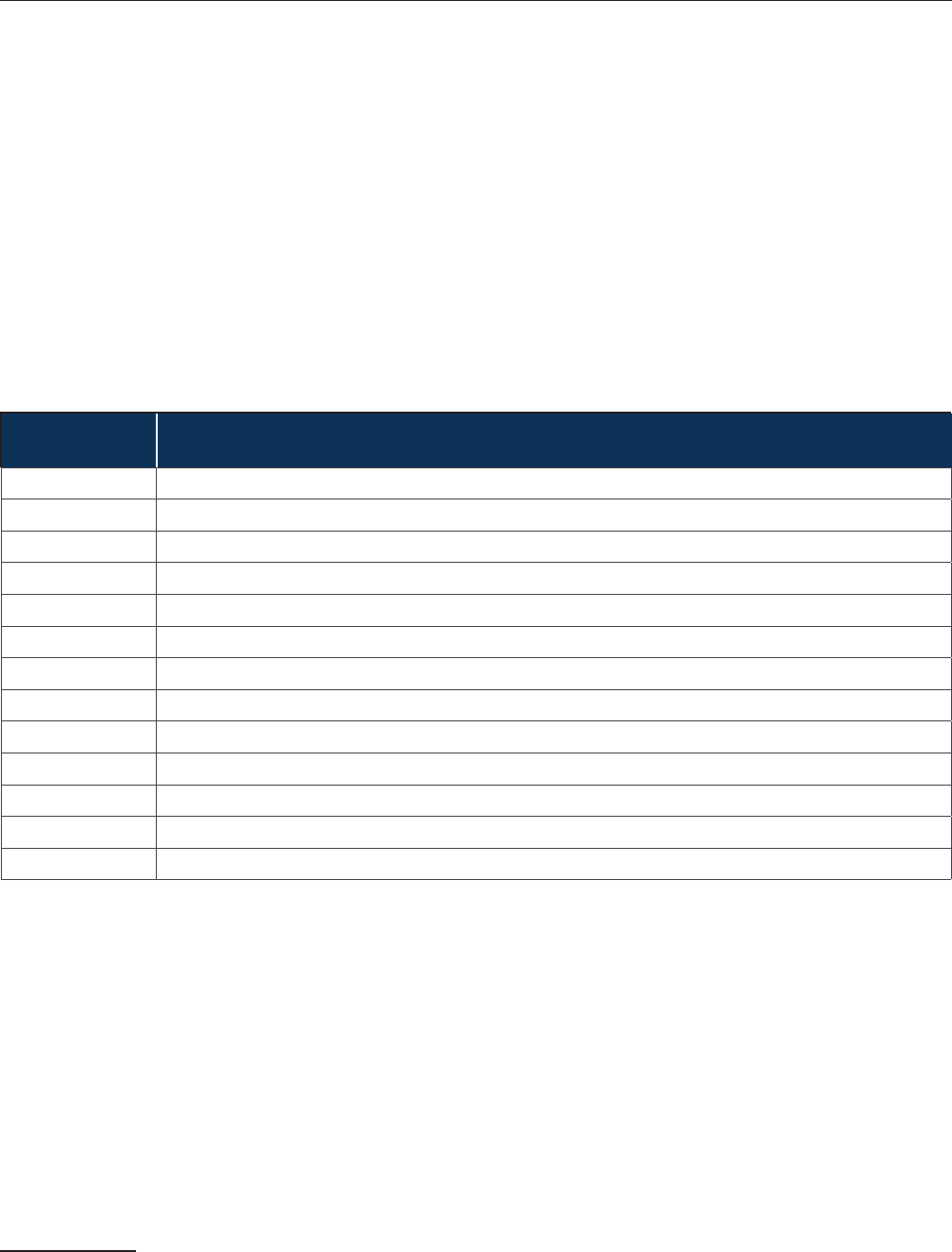

Data on trade in services are more limited. However, using the latest Economic Census data, we

obtained detailed accounting of service exports for 2012. We nd that exports of service-provid-

ing IP-intensive industries totaled about $81 billion in 2012 (compared to $90 billion in 2007).

is accounted for 12.3 percent (compared to 19 percent in 2007) of total U.S. private exports in

services. As shown in Figure 10, exports of soware publishers totaled $22.7 billion and continue

to be the largest group of service exports. However, export by the portfolio management indus-

try, totaling $13.6 billion in 2012, replaced the motion picture and video industry for the second

place compared to the 2007 rankings. e latter went down from $15.3 billion in exports in 2007

to $7.3 billion in 2012 and appears to account for a substantial part of the decline in exports of

service-providing IP-intensive industries. Other major services export categories in 2012 includ-

ed computer system design ($7.8 billion), motion picture and video production ($7.3 billion),

management & technical consulting ($7.1 billion), and wired telecommunications carriers ($5.2

billion).

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

$7.7

$1.4

$1.6

$2.9

$3.3

$5.2

$7.1

$7.3

$7.8

$13.6

$22.7

$0 $5 $10 $15 $20 $25

Other

Machinery and equip rental & leasing

Other telecommunications

Newspaper, book, & directory

Other information services

Wired telecommunications carriers

Manage't, scientific, & tech consult svcs

Motion picture and video production

Computer systems design & related svcs

Portfolio management

Software publishers

Figure 10. Exports of IP-Intensive Service-Providing Industries, 2012

Billions of current dollars

Source: ESA calculationsusing data from the Census Bureau's 2012 EconomicCensus.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

V. Conclusion

e 2012 report Intellectual Property and the U.S. Economy: Industries in Focus identied IP-in-

tensive industries and quantied their contribution to the U.S. economy. It found that in 2010

IP-intensive industries supported over 40 million jobs and accounted for about $5.06 trillion in

value added; equivalent to 34.8 percent of U.S. GDP. e current report provides updated results

demonstrating that IP-intensive industries supported 45.5 million jobs and contributed $6.6

trillion in value added in 2014, equivalent to 38.2 percent of U.S. GDP. In addition, the current

report reinforces the earlier nding that IP use permeates all aspects of the economy with in-

creasing intensity and extends to all parts of the U.S.

Besides data on the prevalence of IP, policy makers are interested in learning more about how

eectively it is used to stimulate economic activity. However, understanding the eectiveness and

benets of IP use requires an understanding of the value that IP owners attribute to their assets,

and how that value translates into incentives for the creation of new goods and services. While an

expansive welfare analysis of IP is beyond the scope of this report, evidence that informs such an

analysis is an important direction for future work.

With more granular data that connects inventors and rms of various types with IP assets, we

could start to answer a variety of questions about the distinct functions of IP in the economy. In

particular, policy makers would benet from research on whether IP users seek IP protection to

facilitate nancial investment in innovation, to support entrepreneurial liquidity, or to enable

technology transfer, and the extent to which these advantages stimulate inventive activity. Under-

standing the role of IP in the performance of diversely situated rms and in the economy overall

requires the application of a variety of methodologies and persistent eorts, many of which are

already underway.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

ppendi

In this Appendix, we provide a detailed discussion of the methodologies used to designate IP-in-

tensive industries for each of the three IP types (i.e. patents, trademarks, and copyrights). e

methodologies follow very closely what was applied in the 2012 report. We also provide a table of

the IP related product codes from the Economic Census which were discussed in the Section IV

under IP revenue.

Paens

Patents are classied in over 450 patent “technology classes” that distinguish their inventive

content.

38

Additionally, the USPTO maintains a general concordance between its technology

classications and 30 North America Industry Classication (NAICS) codes (26 unique codes

and 4 combinations), which enables analysts to associate patents with these industries.

39

We rely

on these NAICS-based patent counts for 2009 to 2013 to identify patent-intensive industries.

40

Just as a patent can be assigned to more than one technology class, it also may be associated with

multiple industries. Because no similar concordances to NAICS are available for plant or design

patents, only utility patents are used in our analysis.

41

is approach strictly limits the patent

analysis to the manufacturing sector because the concordance system only associates patents

with manufacturing industries. Service-providing industries may also rely on utility patents in

their production processes, but these industries are not captured by the patent-NAICS concor-

dance we employ.

racional s. hole Paens Couns

e USPTO reports patent data by NAICS category using two dierent counting measures. e

rst gives one full count to every industry with which a particular patent is associated. e sec-

ond divides each patent by the number of industries it is associated with, thus creating fractional

counts of patents. e sum of the fractional counts equals the total number of patents issued

in a given year, while the sum of the whole counts across industries is greater than the number

of patents issued. Patent analyses within a given industry or technology class commonly use

whole counts; however, cross-industry analyses typically use fractional counts in order to avoid

over-counting. For these same reasons, fractional counts are used in this report.

42

It is important

to note that the NAICS concordance maintained by the USPTO associated each patent with its

38 Utilitypatentsmaybeclassiedintomorethanonetechnologyclassbutareorganizedaccordingtotheirprimaryclas-

sication.

39 ThisconcordancewascreatedbytheUSPTOwithnancialsupportfromtheNationalScienceFoundation.Foran

overview of NAICS, see www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/index.html.

40 Seewww.uspto.gov/web/ofces/ac/ido/oeip/taf/data/misc/patenting_trends/info_ptrends2008.txt.

41 To contrast the scale of technology patents, design patents break out into 33 classes and plants have only one patent

class.Seewww.uspto.gov/web/ofces/ac/ido/oeip/taf/all_tech.htmformoreinformationonutilitypatents.

42 It should be noted that the use of fractional patent counts differs from our treatment of trademarks registrations for

which only whole counts of registrations by class are available.

InellecualProperandheUSconomUpdae

nal use in the economy. In practice, this means that the patents are all associated with manufac-

turing NAICS codes regardless of whether the company that owns them is a manufacturer or a

company that may be classied in the services sector.

43

Mehodolog

Using the USPTO maintained concordance, we calculate a measure of industry patent “intensity,”

dened as the ratio of total patents over the ve years (2009–2013) in a NAICS category to the

average payroll employment by industry. Because employment is a gauge of industry size, divid-

ing patent counts by employment normalizes patenting activity with respect to industry size.

44

is approach helps put all industries on an even playing eld, so that the most patent-intensive

industries are dened not as the ones with the most patents, but rather those with the most pat-

ents per worker.

By using a ve-year period (in this case, years 2009–13) instead of just one year helps minimize

the chance that anomalies in any given year will skew our results. e analysis was performed

at the highest possible level of NAICS industry detail, and so results include four-digit indus-

tries as well as some individual three-digit industries and combinations of three- or four-digit

industries.

45

As shown in Table A-1, most patent-intensive industries in the sample fall into the

four-digit NAICS industries, which may be a product of the patent-intensive nature of these

more nely disaggregated industry sectors.

43 Forfulldetailsonthenatureandcaveatsofthepatentdataused,seewww.uspto.gov/web/ofces/ac/ido/oeip/taf/govt/

naics/explan_naics.htm.

44 Value added and gross output are two alternative gauges of industry size. However, estimates at the level of detail